Hi, I'm a photojournalist who visited Colombia in 2016 with a goal of working a day on a coffee farm and writing a story about it. Unfortunately the piece was never published, but I thought this would be a good opportunity to share a story with the community here. Thanks for reading!

WHAT IT'S LIKE TO "WORK" ON A COLOMBIAN COFFEE FARM

During the wet fall season in Colombia the forecasts read 100% chance of rain every day. 75 kilometers west of Bogota the green hillsides fill with mist and soft showers, dampening the tall coffee plants that terrace the rolling landscape. Today the Finca Esperanza coffee farm is my office.

My black sneakers dig into the sloped soil, perpetually dampened by La Nina as I carefully pick my first beans. Don Alvaro, my 71 years young host, strums coffee branches like guitar strings to pluck only the ripe red cherries while singing songs about, you guessed it, coffee.

His bushy white mustache looks cartoonish, and there’s something comic about the pace of his work. He’s moving just a little too quickly, like someone has pressed fast forward, whereas I’m moving in slow motion. After an hour the straw basket around my waist is still far from full, I’ve picked a pitiful amount of coffee. A drizzle turns downpour and my host sympathetically decides it’s time for lunch.

I follow Don Alvaro and my translator Ana Maria from the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation down a steep stone path towards his house with the bushes and fog at our sides. It frames a great photo, so despite the heavy rain, I turn my camera vertical to include his house in the distance. He looks over his shoulder towards me and my finger clicks and my stupid gringo legs slip out from me and slam my tailbone hard and crumple my forearm underneath me as I juggle my camera, notebook, and pen.

Ana Maria looks like she just saw a ghost, or, a lawsuit.

INTO THE FOG

Like most fans of specialty coffee, I don’t do much back-breaking labor. No part of my body hurts the day after a big writing assignment. I office in coffee shops that serve pour-overs of specialty grade beans for $6. The label lists the farmer’s name, but I rarely stop to consider that a pair of hands picked the beans.

My invitation to Colombia came from the organizers of one of the world’s largest coffee trade shows, but I planned to divert the press trip towards a coffee farm where I could gain some firsthand coffee experience.

The Colombian Coffee Growers Federation made a valiant effort to dissuade me. Blood-stained hands, pulsing insect bites, and back surgeries aren’t exactly PR wins. Plus, my non-existent Spanish skills and expensive denim wouldn’t make me the most welcome coworker. It took about twenty emails and three phone calls, but they eventually agreed.

A van picks me up from my hotel at 7am and we drive two hours to La Finca Esperanza. The first thing that strikes me is that coffee farms don’t smell good. Compost mounds and a minefield of cow patties mix with the sour scent of fermenting coffee cherries. I plug my nose and think of a steaming French press.

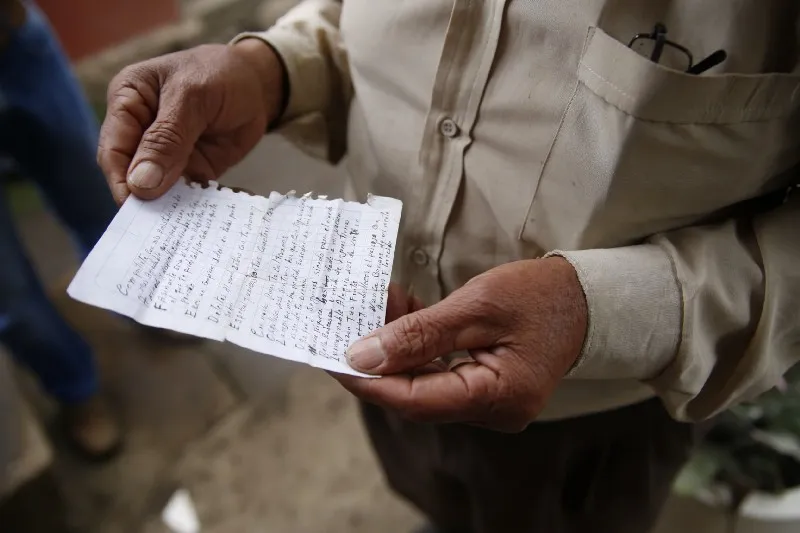

My host self deprecatingly introduces himself as Alvarito, which my translator quickly corrects to Don Alvaro. Don Alvaro is well-vetted to say the least, an affable self-proclaimed peasant with a huge smile and warm eyes. Despite his age he still labors in the fields without a trace lower back pain. He shows me photos of himself wreathed in flowers leading a parade and a handwritten poem about farming. I haven’t seen a happier person in all of Colombia.

I ask Don Alvaro questions in broken Spanish while his assistant Juan works in the background. Juan’s ripped unbuttoned jean jacket reveals a lean boxer’s chest and simple silver chain. I try to say hello, but he dodges my eyes and ducks into the kitchen or behind some farm machinery. I’m here to “work”, but he’s the one who actually has work to do.

ALVARO AND ME

Like all good hosts, Don Alvaro offers guests a steaming cup of coffee. By snobby third-wave standards, farmers typically drink terrible coffee and this is no exception.

Your average working-class Colombian enjoys small strong cups of dark coffee called “tinto”, which roughly translates to “inky water.” Don Alvaro’s recipe: six grams of coffee at the bottom of a cup, add boiling water, top with cold water to sink the grounds, then cover to steam.

It tastes bitter, but there’s no beating the scenery. The 1800 meter elevation creates fantastic rolling landscapes of hills, coffee plants, and fog. The nearest town is named Fusagasuga, which translates to “girl behind the mountains.” Despite 150 years of growing history, the region barely registers on the coffee-producing map. La Finca Esperanza grows on only five acres, which is slightly above the average size of Colombia’s 560,000 coffee-growing operations.

I finish my tinto and head into the fields with Don Alvaro and Ana Maria. Alvaro ties a basket on my waist with rough twine and I’m ready for action. It turns out coffee harvesting only takes 30 seconds to learn: pick the red beans, leave the green ones on the branches, and watch out for poisonous worms as big as your thumb.

Don Alvaro’s hands strafe through the branches effortlessly at three times my speed. From over my left shoulder a handful of coffee flies into my basket courtesy of Juan, who I didn’t realize was right behind me. By the time I turn around, he is already half-way down the hill tending to a cow.

Despite what looks like an endless ripe field, this is actually slow season. No fruit will rot on the leaves, so the pace is best described as “tranquilo.” Birds chirp happy tunes, the temperature hovers in the mid-60s, Alvaro dances the Cabbage Patch. It’s less back-breaking and more whistle-while-you-work.

A SLIP AND A FALL

After an hour I feel great, but between taking photos, scribbling notes, and wrestling with the Spanish language, I haven’t picked much coffee. I’ve only gathered a kilo, whereas a productive member of Alvaro’s five-man peak-harvest workforce would’ve picked 15 times that by now. If Juan is a strong cup of tinto, I’m a pumpkin-spiced latte.

A hard rain sympathetically interrupts my “hard work”. Water soaks my shirt and mist fogs my camera lens. This wouldn’t stop a typical harvest day, but Don Alvaro takes pity on me. Instead of climbing higher into the hills, we head down that steep stone path back to the farm.

My sneakers slip on a jagged stone and my legs skid out, arms crumbling underneath me, but not quick enough to shield my lower back. I hit the ground hard and my thoughts fast forward to foreign hospitals, surgery, and horrible embarrassment. I should’ve just stuck to tasting fancy coffees at the expo.

Back in the present, I don’t feel anything but wet. I lay still a moment bracing for a burst of pain and a lifetime of explaining this stupid idea.

But it doesn’t come.

I jump right up. I’m okay! Everything’s fine!… I hope?

The rain stops. I wipe mud from my sleeves. Juan suddenly reappears, shaking his head in disappointment. I ask Alvaro if he’s ever had any serious falls. He says no. We walk silently back to the house and, for good measure, I step in a soggy cow patty.

ALL IN A DAY'S WORK

Next on the schedule is a lesson from Don Alvaro on how to turn coffee cherries into coffee beans. First he soaks the ripe beans in water. Hollow cherries float and are discarded. Then the beans are dried using a method called “pulped natural processing”. Farmers peel the skin off the ripe cherries to expose the sticky mucilage around the bean, then the beans ferment in the sun for 18 hours, and finally a machine finishes the drying process. This process can lead to slightly sweeter cups, but also funkier floral flavors.

As we sift through the soaking beans, I finally introduce myself to Juan. I use my best toddler level Spanish to explain that I’m a journalist visiting from the United States and Juan smiles and asks about my presumably close friendship with Barack Obama. Turns out he’s great at jokes.

While I was busy “getting my ass kicked in the fields,” Juan’s wife prepared lunch. Finca Esperanza grows additional crops to shade their coffee plants, and since banana trees are perfect sun umbrellas, fried plantains comprise a big part of Don Alvaro’s food pyramid. Hunks of yucca in pink tomato sauce, baked potato, rice, neon ripe avocado slices, and crispy chicharrones round out the menu. It’s a ridiculously large portion of food.

I’m informed that if I don’t finish it, I’ll have to wash the dishes. Juan quickly clears his plate, but the thick starches sit heavy in my weak stomach. I can barely eat half of the food, but no one hands me a dish towel afterwards. Once again, I’ve again proven myself a hopeless guest, but try to make amends with a gift.

Nationalism and import regulations mean most Colombians haven’t ever tasted African coffee, so I brought some Ethiopian beans from one of my favorite Texas roasters, Tweed. Don Alvaro smells it and his eyes light up. I suggest we drink it, but he insists that he save it for his family back in Bogota. He pours another round of pitch black tintos.

THE LONG RIDE HOME

I ask if it is time to go back to the fields, but my translator says we’re done picking for the day. The Coffee Federation wants to show me more stages of coffee supply chain, and Alvaro tags along since he needs a ride back to his family in Bogota.

We stop at a purchasing warehouse, plant nursery, coffee council building, and a roastery with a small gift shop masquerading as a cafe. Each stop offers more context as to how the coffee fruit turns into my favorite beverage, but also reveals stark realities. As we leave the nursery where I pose for a silly photo planting coffee seeds, I learn that it is staffed entirely by victims of narco violence.

The long drive back to Bogota gives me plenty of time to ask Don Alvaro questions. Fog masks the sunset along the winding hillside roads and within an hour the skies go pitch black. In very broken Spanish we talk about books, music, Colombian history, farming, his family, the Internet, and of course, coffee.

Then at the outskirts of Bogota we hit horrible gridlock and Don Alvaro’s youthfulness fades. He’s no longer that spry Colombian singing while picking coffee, he’s a grandfather out far past his bedtime.

Another hour passes and we barely move. I ask how long the drive will be and Don Alvaro stoically stares straight ahead, then nods slightly and pauses. I lean forward. He says we’ll just have to be patient.