An alternative perspective on mental health and addiction.

Contents

Forward

What if Doctor is Wrong? : The Research and Practices

Chapter One: Basic Instinct

Chapter 2: The Importance of Words (Part 1)

Chapter 2: The Importance of Words (Part 2)

Chapter 2: Citations, Bibliography and additional sources

Chapter 3: But I Don't Have Trauma

(part 2)

“The anxiety in this reaction is allayed, and hence partially relieved, by depression and self-depreciation. The reaction is precipitated by a current situation, frequently by some loss sustained by the patient, and is often associated with a feeling of guilt for past failures of deeds.” 26 (American Psychiatric Association, 1952, pp. 33–34)

What the DSM-I describes in the above paragraph referring to depressive reaction, is identical to what we would now understand to be a type of C-PTSR “flashback”.

Simply put…

a “trigger” in the present environment or situation causes a “flashback” (often unconsciously) reminding the person of a past traumatic event or circumstances…

and the perception and feelings associated with the past event become overlaid onto the present moment.

This is how trauma “works”.

But we will look more at how trauma works (and why some people aren’t even aware they have trauma) in the next chapter, where it will also become clearer as to what the many mental health "disorders" of today may possibly be.

An Interesting Story

“We cannot change anything until we accept it.

Condemnation does not liberate, it oppresses.”

THE YEAR IS 1904

"

Sabina Nikolayevna Spielrein was a Russian physician and one of the first female psychoanalysts. She was in succession the patient, then student, then colleague of Carl Gustav Jung… 27

Following the sudden death of her only sister Emilia from typhoid, Spielrein's mental health started to deteriorate, and at the age of 18 she suffered a breakdown with severe hysteria including tics, grimaces, and uncontrollable laughing and crying. 27

After an unsuccessful stay in a Swiss sanatorium, where she developed another infatuation with one of the doctors, she was admitted to the Burghölzli mental hospital near Zurich in August 1904. Its director was Eugen Bleuler, who ran it as a therapeutic community with social activities for the patients including gardening, drama and scientific lectures. 27

One of Bleuler's assistants was Carl Jung, afterwards appointed as deputy director. In the days following her admission, Spielrein disclosed to Jung that her father had often beaten her, and that she was troubled by (sexual) masochistic fantasies of being beaten. 27

Original Image Source: Carl Jung: By Unbekannt - This image is from the collection of the ETH-Bibliothek and has been published on Wikimedia Commons as part of a cooperation with Wikimedia CH. Corrections and additional information are welcome., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org | By Unknown author - Family photo, Public Domain

Bleuler ensured that she was separated from her family, later requiring her father and brothers to have no contact with her. 27

She made a rapid recovery, and by October was able to apply for medical school and to start assisting Jung with word association tests in his laboratory. Between October and January, Jung carried out word association tests on her, and also used some rudimentary psychoanalytic techniques. 27

Later, he referred to her twice in letters to Freud as his first analytic case, although in his publications he referred to two later patients in these terms.” 27

Sabina Nikolayevna Spielrein made a full recovery and went on to become a leading Psychoanalyst in her own right.

Psychoanalysis worked.

The psychodynamic, psychosocial approach worked.

Mental health professionals had already gained enough insight to "cure" mental "illness".

But somehow, in 2022, the latest version of the DSM claims this reaction to be a disorder and modern treatment commonly includes psychiatric medication.

How did we progress to this point and is this progress?

The DSM-II

The next edition of the manual, the DSM-II, was issued in 1968. It made some changes to the DSM-I, mostly to make the nomenclature more compatible with the World Health Organization's International classification of diseases (ICD). 7

The DSM-II is where the words used to describe these reactions begins to change.

Although the DSM-II no longer used the term “reaction” (e.g. “Schizophrenic Reaction” became “Schizophrenia,” “Phobic Reaction” became “Phobic Neurosis,” etc.), the second edition maintained the general psychodynamic orientation of the first DSM. 7

It made few changes in the definitions of the various diagnoses and continued to describe each condition in perfunctory and theory-infused ways. For example, its definition of depression (now called “depressive neurosis”) stated: “This disorder is manifested by an excessive reaction of depression due to an internal conflict or to an identifiable event such as the loss of a love object or cherished possession”. 7

Both manuals focused on psychodynamic explanations that directed attention toward the total personality and life experiences of each individual patient {my boldface]. 7

So the word “reaction” is replaced by the word “neurosis” and the word “disorder” first appears. Although “disorder” is first used only in the description of the behaviours associated with these “neurosis” in the above paragraph taken from the DSM-II.

A strong move away from a psychoanalytic perspective, however, towards a biological perspective of disease, genetics and medical illnesses had begun.

This became the standard mainstream perspective of mental health conditions in 1980, when the DSM-III was released.

In 1980 the word “disorders” replaced “neurosis” in full and was added to every category of reactions in the “Bible of psychiatry and psychology”.

But how and why did this happen?

While the terminology, in the DSM-II, for these reactions was becoming more medicalised, the focus on treatment was still generally holistic and psychodynamic.

Mental health practitioners focused on understanding the individual and interpreting their behaviours. The focus was on understanding why there was neurosis (psychological conflict), in order to help people integrate their personal experience and accept it, and themselves, fully.

This was the process, and goal, of "individuation" that Carl Jung referred to.

It was not necessary, with this approach, to assign a diagnosis to a person suffering with mental health challenges.

Even more importantly, specific diagnoses had little role to play in the explanations and treatments of dynamic psychiatry or in mental health practice. 7

Psychodynamic therapies were largely nonspecific, so particular diagnoses were unnecessary for guiding treatment plans. Most outpatients at the time paid for their own therapy so that no private or public third parties required diagnoses to reimburse clinicians. 7

In addition, during the 1950s and 1960s drug companies generally touted many of their products as allaying broad conditions such as stress, nerves, or anxiety, not as responses to particular types of mental disorders. 7

There was no need to make a diagnosis in order to claim funds back from health insurance to cover treatment. Yet.

The absence of specific definitions of the conditions found in the DSM-I and DSM-II were not liabilities for mental health practitioners or the pharmaceutical industry during the 1950s and 1960s. 7

Enough said.

And now human ego and greed become clearly involved.

A Wrong Turn

It happens in the institutions of education where, to this day, mental health professionals are “taught” what they now “know”.

While departments of psychiatry in communities and institutions were still dominated by psychoanalysts who were focused on Freudian theories, psychiatrists were not being taken seriously because psychoanalysis was not considered science or medicine.

“I remember one meeting, when I told a psychiatry professor about a study I had read showing that no two psychiatrists could agree better than chance on diagnosis,” says retired Washington University psychiatrist George E. Murphy, MD. “He said, ‘But then our diagnoses don’t mean anything,’ and I replied, ‘That’s exactly true.’ And he never spoke to me again, because that was too bitter a pill to swallow. 28

Between 2018 and 2020 I was diagnosed with three different "disorders", by three different professionals. It seems, in 2022, not much has changed.

In the 50’s and 60’s, however, academic papers on psychiatry at universities were not being taken seriously and academics were unable to get funding and grants to further their studies.

As a result of this, there was a strong move towards developing a more scientific model of psychiatry.

In an interesting article I found, Washington University is specifically mentioned as a forerunner in this shift towards a more scientific approach to mental health conditions.

In their profound disagreement with the psychoanalytic model — and their determination to forge a new, evidence-based brand of psychiatry — Washington University psychiatrists stood virtually alone. At scientific meetings, they were often shunned, their papers ignored; they faced rejection upon rejection in applying for research grants. But they persevered. 28

“There was a spirit in that department of open thinking about psychiatric illness, a kind of free-floating intellectual energy,” says Charles F. Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “The faculty were very bright and very articulate, and the place became a magnet for these creative people to come together." 28

Creative people. Because psychology is not science. Again. It is philosophy and personal opinion at best.

It’s important to note here that a psychologist is not a medical doctor.

So, what is the difference between a psychologist vs a psychiatrist? A psychologist studies how our brains and our bodies communicate with each other. A psychiatrist studies how medication and psychotherapy can be used to treat various mental and behavioral disorders. Psychiatrists prescribe medication. Psychologists don’t. 29

But in the 50’s and 60’s even psychiatrists weren’t considered to be real doctors because the psychoanalytic approach to treating mental health conditions was not considered medicine or science.

This resulted in those working in the health arena, such as psychologists and social workers, saying they were just as qualified as psychiatrists to treat people with the popular psychodynamic approach..

Psychiatrists were also challenged by other mental health professionals such as clinical psychologists and social workers who argued that they possessed as much training and skill to study and treat psychosocially defined conditions. 7

There was, in other words, nothing explicitly psychiatric about the assumptions of the first two DSMs: nonmedical and medical professionals alike could diagnose and manage most of the entities that they defined. 7

So not much respect for the psychiatric field at all.

This drove academics, the students and researchers of psychiatry, towards a more medical perspective that might be considered more scientific.

These:

*... university psychiatrists moved their field toward a new “medical model” of psychiatry that culminated in the publication of the DSM-III in 1980. 28

It was in the revision of the DSM-II (to the DSM-III) that the word “disorder” replaced the word “neurosis” in full and all reference to the psychodynamic approach to mental health conditions was eradicated in one fell swoop because:

... psychodynamically oriented practitioners were being challenged by the emergence of an energized group of biologically oriented researchers... [my boldface] 7

Biological psychiatrists... emphasized the grounding of mental illness in brain structures and functions. 7

They also employed psychoactive drugs as opposed to talk therapies as the first-line response to psychiatric conditions. 7

And here is how it happened…

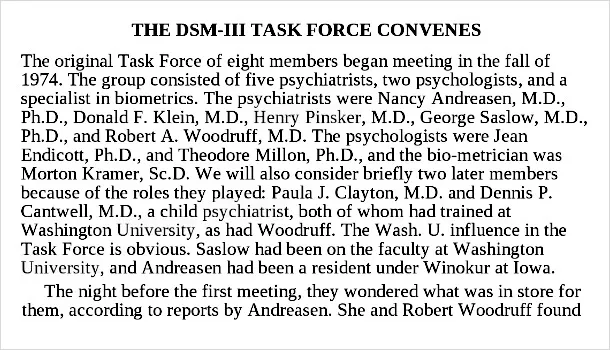

The DSM-III Task Force

In 1942, Washington University’s [my boldface] combined Department of Psychiatry and Neurology attracted a new head, Edwin F. Gildea, MD, a Yale psychiatrist and dedicated researcher [my boldface]. A Harvard colleague, Mandel Cohen, MD, was delighted at Gildea’s appointment. A staunch foe of psychoanalysis in a city dominated by analysts, Cohen was eager to spread his scientific approach, and he urged a talented protégé, Eli Robins, MD, to accept an appointment in Gildea’s department. 28

Robins arrived at the university in 1949 with his wife, Lee Nelken Robins, PhD, later a key founder of psychiatric epidemiology. In 1954 came George Winokur, MD, a strident enemy of psychoanalysis, followed the next year by Samuel B. Guze, MD, a skilled internist who shifted to psychiatry. These three worked closely and collegially, joined by others: Murphy, Richard W. Hudgens, MD, Robert A. Woodruff Jr., MD, Paula J. Clayton, MD, Ferris N. Pitts, MD, Donald W. Goodwin, MD, and Rodrigo A. Muñoz, MD. 28

The academic psychiatrists at Washington University start a band that includes as many opposers of psychoanalysis as possible.

Robert L. Spitzer was then asked to chair the American Psychiatric Association’s task force to develop the DSM-III because he was directly involved in the development of the DSM-II as well.

Who was Robert Spitzer, you may wonder?

Spitzer was a major architect of the modern classification of mental disorders. 30

He developed psychiatric methods that focused on asking specific interview questions to get at a diagnosis as opposed to the open-ended questioning of psychoanalysis, which was the predominant technique of mental health. He co-developed the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), a screening technique used for diagnosing bipolar disorder. He also co-developed the Patient Health Questionnaire (PRIME-MD) which can be self-administered to find out if one has a mental illness. 30

Some years later..

Spitzer was briefly featured in the 2007 BBC TV series The Trap, in which he stated that the DSM, by operationalizing the definitions of mental disorders while paying little attention to the context in which the symptoms occur [my boldface], may have medicalized the normal human experiences of a significant number of people. [my boldface] 30

But by 2007 the damage had, long since, already been done.

In my own experience, and after personally talking to some of the victims of modern psychiatric "treatment", may is also somewhat of an understatement.

Back in the 70’s, however, Spitzer was still interested in formalising diagnoses into a more medical, scientific model.

It makes sense that Spitzer selected five members (out of the nine on the task force for the DSM-III) who had trained, or had been educated, at Washington University.

All of whom had a biological (medical) perspective on the causes of mental health conditions and some of whom Spitzer had personally collaborated with prior to his position as head of the task force.

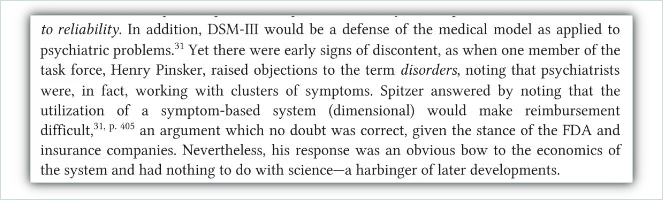

During meetings for what was to become a radical shift towards a medical perspective on mental health, there was only one person on the committee who has been said to have had concerns about the new nomenclature.

Dr Pinsker, coming from a psychoanalytic approach, raised an objection to the term “disorders” being added to the categories of behaviours in the DSM.

To which Spitzer replied that reimbursement from medical insurance would be difficult if the classifications were based on sets of symptoms and were not specific.

By Charles E. Dean

This concern was valid because:

In the 1970s psychiatrists confronted a new economic context. Government and private insurance programs were beginning to pay for most outpatient treatment. The vague and amorphous conditions in the DSM-I and DSM-II did not fit an insurance logic that required that clinicians treat a distinct disease. 7

This ... required a system that could more precisely measure the conditions that clinicians were treating. The economic well-being of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals began to depend on their ability to treat specific, reimbursable conditions. 7

In addition…

… the Food and Drug Administration began to enforce its rule that psychoactive medications could only be promoted as treatments for specific, well-recognized psychiatric disorders but not for psychosocial problems or general distress. 7

Spitzer had been approached by the FDA some time back. I found an interesting paper by Spitzer where he shares more about his personal history:

"I wrote the paper, “An Examination of Wilhelm Reich’s Demonstration of Orgone Energy” (my first scientific paper), describing these experiments and the negative results. 31

I submitted the paper to the American Journal of Psychiatry, which rejected it. Soon thereafter, while still at Cornell, I was visited by someone from the Food and Drug Administration, who explained that the government was attempting to stop Reich from distributing orgone accumulators. He asked me if I would be willing to serve as an expert government witness against Reich. Apparently, the FDA had asked the American Psychiatric Association (APA) who they could recommend as an expert on Reich’s orgone theories. The APA suggested that the FDA contact a premedical student at Cornell (me) who had recently conducted some experiments on Reich’s theories of orgone energy.” 31

I wonder if Spitzer maintained a relationship with any members of the FDA?

It's mentioned, repeatedly in accounts of this history, that Spitzer was an easy going, affable kind of fellow. I have no wish to paint any of the task force members as malevolent human beings.

Many of them, in later interviews, go on to say that they had little idea things would end up the way they did.

As in the alarming amount of new "diagnoses" that have been created, the loss of traditional psychoanalysis in treatment of mental health conditions and the inordinate amount of psychiatric medications now being prescribed as standard practice.

They were human beings with their own personal perspectives and opinions. And their own motives.

Hence, when decisions were made to change the nomenclature in the DSM-III, it was only Henry Pinsker, who raised an objection to the word "disorder" replacing the word "neurosis" in full.

Other than this, there has been mention of how delighted the task force was to, so easily, have reached decisions on their revision of the DSM.

Perhaps that's because the DSM-III task force was a small group of individuals with an already mostly agreed upon opinion…

which is what psychology is.

The opinion of nine odd people who were all Caucasian and mostly male (7 men; 2 women) Americans.

With a personal motivation to be taken more seriously professionally and to be able to access funds for further academic research.

Which would also facilitate mental health professionals being able to add an ICD code to invoices.

Which would enable clients to claim funds back from insurance.

Funds from medical insurance companies who would not pay out insurance for "patients" who did not have some kind of medical illness or “disorder”.

Which would facilitate an increase in the number of people who would be able to afford private treatment.

And prescriptions of psychiatric medication.

Of course.

For which the FDA had begun to enforce stricter measures.

Moreover, the Food and Drug Administration began to enforce its rule that psychoactive medications could only be promoted as treatments for specific, well-recognized psychiatric disorders but not for psychosocial problems or general distress [my boldface]. Like psychiatrists, the increasingly influential pharmaceutical industry required a better defined system of classification than was found in DSM-II. 7

There was more than enough motivation to medicalise these conditions as quickly as possible.

We all know how lucrative the multi-billion dollar pharmaceutical industry is.

As is private treatment for mental health and addiction.

I wonder who appointed Spitzer (the friendly, affable fellow) as head of the DSM-III task force?

I have not, yet, been able to find out.

The Rise of Psychiatric Medication

As drug companies began their marketing campaigns in earnest, psychiatric medication became popular as a first line of treatment for mental health reactions.

The Official Newspaper of the American Psychiatric Association (the Psychiatric News) Vol IV No.1 (January 1969) has nineteen half to full pages of advertisements for psychiatric medications.

With multiple full page journal articles that promote the use of them as well.

This makes me smile.

This was the medication I was on for many years. Stelazine was prescribed for schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is commonly considered to be a serious and incurable mental illness of some sort that elicits a great deal of fear in the general public.

But schizophrenia is really just a blanket term for a cluster of behaviours that no medical professional has managed to explain yet. Nothing more than a made up word with a list of behaviours and thinking associated with it.

Reactions.

As it was originally called in the DSM-I.

Schizophrenic reaction.

As it turned out, the demon was never “only in my mind” and addressing the root causes of my mental distress healed me in full.

The forerunners of psychoanalysis were right.

Again.

In addition, Stelazine worked perfectly well to minimize the reactions caused by my trauma and cost around R120 (roughly $7.50) per month.

In 2018, Stelazine was discontinued and its replacement, Seroquel, hit the market for just under R1000 ($65) a month.

It was at this exact time that my recovery into full mental health began in earnest. I decided not to take the new medication because I couldn't afford it and was also afraid of possible side effects.

And I began to focus on managing my reactions naturally instead.

Please do not do this without the consent and support of trained professionals. It is extremely dangerous.

What followed was an experiential journey of three very difficult years into finding and addressing the root causes of my mental health challenges and healing them.

It was only when I stopped taking any mind altering substances (including the prescription medication that was supposed to be helping me) that I was able to observe my reactions clearly enough to make connections as to what “triggered” them.

Over time, I was able to create a map of sorts and find my primary traumas.

Because trauma becomes a network.

If one addresses the root trauma it seems, in my personal experience, to take care of any other events where the primary traumas were unconsciously repeated or recreated.

As Jung said:

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

The forerunners in mental health were totally correct in my case as well.

There were only two primary traumas that I needed to address (as it turned out) and neither of them were intentionally created by the people involved. My parents. Good people who had unresolved trauma themselves.

I will explain more how this works in the following chapters.

Back to the Psychiatric News and the enormous amount of advertising space being sold to pharmaceutical companies.

This next advertisement only makes me sad.

Here we see the pathologizing of childrens’ behaviour begin.

And parents possibly opting for the simpler solution of medicating their children (being encouraged by the medical profession now), instead of addressing possible causes of behaviours.

Reactions (and subsequent behaviours) that could easily be addressed by better quality parenting time, facilitated by assisting and healing parents who were probably suffering from PTSD and C-PTSD after the war.

ADHD?

I no longer believe there is any such “disorder” either.

And I can’t quite wait to show you why.

This is the earliest volume of the Psychiatric News that I could find in the American Psychiatric Association’s newspaper archives.

I wonder what the advertisement ratio was between the first edition to this one and whether there’s an increase in advertising that correlates to an increase in popularity of prescriptions for psychiatric meds in that quarter or year?

Around this same time, another situation had unfolded that also encouraged the use of psychiatric meds..

The deinstitutionalization of mental patients, which began in the 1950s and accelerated in the 1960s, posed another challenge to the dynamic perspective of the DSM-I and DSM-II. ...In particular, they seemed to require regimens of drug treatments and supportive social resources...

The need of policy makers to respond to the growing number of seriously disturbed patients in community settings further marginalized psychoanalysis and, correspondingly, the diagnostic manual that reflected their assumptions. Psychiatrists were forced partially to shift their attention back to the severely ill patients that had been at the center of attention before the publication of the DSM-I. 7

The easiest way to "flatline" people who have severe mental and emotional reactions, is to simply keep them (heavily) medicated.

And, to reiterate, the pharmaceutical industry is a multi-billion dollar business.

Everything mentioned above, according to numerous sources, motivated and influenced the revision of the DSM (DSM-III).

The DSM-III

This manual was very different from the DSM-I and DSM-II. It featured precise, symptom-based classifications, not perfunctory definitions.

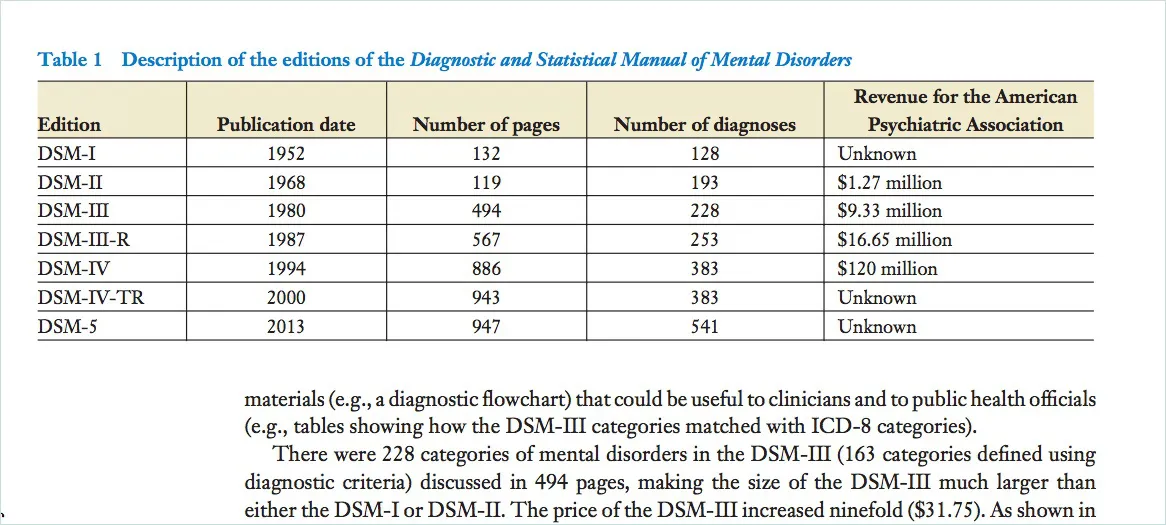

The number of diagnoses grew from 182 to 265 and the manual itself burgeoned from 134 to 494 pages. [my boldface] 7

That's a lot of new "disorders" voted into existence for just one revision, isn't it?!

The manuals following the DSM-I and DSM-II also facilitated the movement of psychiatry to a pharmacologically oriented specialty that targeted the symptoms of mental disorders, rather than their underlying causes. [my boldface] 7

It is in this edition, the DSM-III, that the psychodynamic approach was largely (or completely) abandoned and the word “disorder” replaced the word “neurosis” in full.

The perspective that mental health conditions were understandable reactions, to unprocessed past events and current external situations, that could be treated with psychoanalysis was discarded. Instead, "disorders" were voted into existence by a task force of nine Caucasion, mostly male, American human beings.

Some of whom may have had an interest in renaming "neuroses" as "disorders" for their own personal and financial purposes.

Or who may have been under some encouragement to do so by external parties.

Robert Spitzer on DSM-III: A Recently Recovered Interview

By Christopher Lane, PhD - February 26, 2022 32

Lane: Let’s go back to the key issue of pathologizing and de-pathologizing. Taking you further back to 1968, if I may, with the publication of DSM-II, you co-published with Paul Wilson “A Guide to the APA’s New Diagnostic Nomenclature.” The article is of great interest to me because in it you discuss “the elimination of the word ‘reaction’ from labels such as ‘schizophrenic reaction,’ ‘paranoid reaction,’” and so on—a major development, surely, in how we conceptualize and describe psychiatric diagnosis. Was there lengthy discussion at the time about making that change? 32

Spitzer: About doing that? No, there was no discussion at all. No, no. You have to understand: the APA had decided with DSM-II to use the ICD-8. The ICD-8 was written by one person, [Sir] Aubrey Lewis at the Maudsley [Institute of Psychiatry, London], and he didn’t have the word reaction so, for us, there was never any discussion. 32

Apologies. I need to interject here and point to this as a matter of interest: (Sir Aubrey Lewis)

Lewis was a member of the Eugenics Society. A chapter he contributed to a 1934 book on 'The Chances of Morbid Inheritance', edited by Carlos Blacker, has been described as 'remarkable for its total admiration for the German work and workers", including Ernst Rudin. 33

Ernst Rüdin (19 April 1874 – 22 October 1952)[1] was a Swiss-born German psychiatrist, geneticist, eugenicist and Nazi 34

Let's just look at this again:

Spitzer: About doing that? No, there was no discussion at all. No, no. You have to understand: the APA had decided with DSM-II to use the ICD-8. The ICD-8 was written by one person, [Sir] Aubrey Lewis at the Maudsley [Institute of Psychiatry, London], and he didn’t have the word reaction so, for us, there was never any discussion. 32

Lane: But deleting the word reaction from quite a few designated kinds of mental illness—in a diagnostic manual that’s also meant to define them and for clinicians to recognize them—is still a major shift because it’s altering the ontological status of the condition … 32

Spitzer: Yes. Yes, it is a major shift. I think if there had been any discussion, it would in the order of ‘We don’t add anything by just putting the word reaction to everything.’ You can still believe in psycho-biology without having the word [reaction] there. That would have been the argument. But I doubt there was any argument, because by that time, just having the word reaction didn’t mean very much. 32

Lane: Except that removing it meant you were in effect turning a reaction to something into more like a lasting, possibly lifelong state. One without an obvious cause, in that you also removed stressors that might be tied to environment, economic status, family dynamics, and so on … 32

Spitzer: Well, what we were saying is ‘Dropping the word reaction doesn’t really mean anything.’ I think that’s probably true—I don’t think it did mean very much. With DSM-III there were huge controversies over this and other developments when it came out. But with DSM-II, I guess there was one article, possibly in a newspaper, where William Menninger suggested that by adopting [European-based] ICD-8 we’re losing the contribution of American psychiatry. Now whether he was responding to the reaction thing I don’t recall. I know there was that one complaint. 32

This is Spitzer’s reply?

That removing the word reactions “doesn’t really mean anything”?

He didn’t “think it did mean very much”?

This is his reply to Lane correctly stating:

"Except that removing it meant you were in effect turning a reaction to something into more like a lasting, possibly lifelong state. One without an obvious cause, in that you also removed stressors that might be tied to environment, economic status, family dynamics, and so on …" 32

As the DSM went through a few more revisions and subsequent editions, the problems with the manual became ever more evident.

The DSM-5

The DSM-5, was published in 2013; it is a massive 947-page [my boldface] tome that defines about 300 conditions in precise detail. The imposing nature of the extant DSM-5, however, disguises the intense uncertainty, factionalism, hostility, and political wrangling that has accompanied the development of each DSM since its third edition in 1980. [my boldface] 35

The bitter controversies that marked the DSM’s latest revision sunk the credibility of the manual to levels not seen since the anti-psychiatric climate that marked the 1960s and 1970s. The new critics of the DSM-5 were not the anti-psychiatrists, feminists, and gay advocates who objected to earlier versions but eminent figures within the profession including former NIMH directors and the leaders of the DSM-5 Task Force itself. [my boldface] 35

People who were educated and skilled enough to be concerned. People who were privy to the inner workings of the task force selected for the new edition.

…it was discovered that the organization that produces the DSM— the APA — receives substantial drug industry funding and that the majority of individuals who serve as diagnostic and treatment panel members also have drug industry ties [my boldface] (Cosgrove et al. 2009, 228–32). 36

The fact that 100 percent [my boldface} of the individuals in two DSM panels (Schizophrenia and Psychotic Disorders; Mood Disorders), for example, had financial ties with industry [my boldface} (e.g., served on speakers’ bureaus, corporate boards, received honoraria) is particularly problematic because psychopharmacology is the standard treatment in these two categories of disorders [my boldface} (Cosgrove et al. 2006, 154–60). 36

... the APA instituted a conflict of interest policy for the first time in its more than fifty-five-year history. However, of the twenty-seven task force members who will oversee the development of the DSM-V, only eight reported no industry relationships. When 70 percent of the task force members for the DSM-V have industry ties [my boldface] (representing a relative increase of more than 20 percent compared to the DSM-IV), it is obvious that disclosure alone is not enough of a safeguard for restoring public trust or protecting patients’ welfare (Cosgrove, Bursztajn, and Krimsky 2009, 2035–37). 36

Despite increased transparency, financial relationships between DSM panel members and the pharmaceutical companies that manufacture psychotropic drugs persist. 36

This is the “Bible of psychiatry and psychology" and the main instrument the majority of mental health professionals rely on to "diagnose" their "patients".

A book containing a variety of mental disorders that are voted into existence by the task forces mentioned above.

Voted into existence disorders that are now, generally believed to be, “chronic medical illnesses” that require chronic psychiatric medications for lifetimes of management.

How Disorders are created

A disorder is voted into existence.

For each version of the DSM, a task force is selected to vote unanimously on what thoughts, feelings and set of behaviours should be considered “disordered” to begin with.

This is not hard science.

This is opinion.

And opinion is always guided by current societal “norms”, politics and personal perspective.

And personal perspective is often influenced by personal motivation.

And personal motivation is regularly skewed by personal gain.

Even if that personal gain is simply to avoid being ostracized by a community or fraternity.

The "disorders" in the DSM are opinion.

Opinion and a perspective that can be – and at times has been – swayed by the pharmaceutical industry.

The task force, allocated to revising the DSM, is required to vote unanimously on what a "disorder" should be named and what criteria the “symptoms” of the “disorder” should be adhered to (duration, number, etc.) for a proper "diagnosis" to be made.

The size of the task force has varied from between 9 to to around 30 professionals, per task force committee, over the years.

A very small portion of a very specific demographic, of a relative handful of psychiatrists, psychologists and associated parties of the United States of America.

Although the DSM is the classification manual of mental disorders by and for the U.S.A., it is used, globally, by a variety of other countries as the “Bible of psychiatry and psychology” as well.

It is even given to students in European countries that follow WHO’s ICD more closely as a diagnostic reference. These students still have the DSM included in their course material during their studies.

I'll just list some facts about revisions in DSM, over the years, so you can get a sense of how this works.

Hysteria - once considered to be a problem associated with only women. The word hysteria originates from the Greek word for uterus - Hysteria was finally removed from the DSM as a disorder in 1980

BPD, borderline personality disorder - added to the DSM in 1980

Controversial diagnoses, such as pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder (PMT as we commonly refer to it) and masochistic personality disorder, were considered and discarded

Homosexuality was removed from the DSM as a personality disorder in 1973; kept in as "ego-dystonic homosexuality" and a variety of other classifications, over the revisions, until it was removed as "gender identity disorder" in 2013. It has, however, been replaced with "gender dysphoria". (yes - it is still listed in the Diagnostic statistical manual of mental disorders in 2022)

DSM-5 : childhood-onset fluency disorder (a new "disorder" name for stuttering)

… change was announced earlier this week as part of the newest version of the manual, the ICD-11. The removal of “transsexualism” means transgender people will no longer be classified as having a mental illness by the WHO… The diagnosis of “transsexualism” was renamed “gender incongruence” and moved from the “Mental and Behavioral Disorders” chapter to the “Conditions Related to Sexual Health” chapter. Still listed in the International Classifications of Disease manual in 2022. 37

Autism was originally described as a form of childhood schizophrenia and the result of cold parenting, then as a set of related developmental disorders, and finally as a spectrum condition with wide-ranging degrees of impairment. Along with these shifting views, its diagnostic criteria have changed as well. 38

In the DSM-II, in 1968, dissociative identity disorder was called hysterical neurosis, dissociative type and was defined as an alteration to consciousness and identity. In 1980, the DSM-III was published and the term "dissociative" was first introduced as a class of disorders.The DSM-IV, in 1994, addressed this somewhat as it included the specific criterion of amnesia to the diagnosis of multiple personality disorder, now renamed to dissociative identity disorder. 39

The terminology used to describe the symptoms of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or ADHD, has gone through many changes over history, including "minimal brain damage", "minimal brain dysfunction", "learning/behavioral disabilities" and "hyperactivity". 40

DSM-5: Caffeine Withdrawal

Paradoxically, although hypersexual disorder was rejected by the American Psychiatric Association for DSM-5, on 1 October 2015 the use of the diagnostic codes of ICD-10 became obligatory in the United States, enabling its diagnosis. These codes are included in parentheses and gray text in DSM-5 next to the DSM-9-CM codes presented in bold type

In the ICD-10, the category ‘excessive sexual drive’ was included as F52.7; this category, which reflects dated and pejorative terminology [my boldface], is: 41

“Both men and women may occasionally complain of excessive sexual drive as a problem in its own right, usually during late teenage or early adulthood. When the excessive sexual drive is secondary to an affective disorder (F30-F39), or when it occurs during the early stages of dementia (F00-F03), the underlying disorder should be coded. Includes: nymphomania satyriasis.” 41

The ICD was not much better, although it does seem to have diverted from the DSM towards a more trauma informed approach recently.

In case you're wondering why there is a "CM" on the end (DSM-9-CM in paragraph 11), there are ICD-CM codes as well. The ICD-10-CM is the version of the ICD used in the U.S.A.

This version allows non-physicians (including social workers, nurses, case managers etc) to add codes that are not included in the ICD-10-CM.

New codes can be added, by people in care services, for health concerns created by social, economic, or psychological factors that are not included in clinical diagnoses.

Here we have people who are not doctors (just as we did during the 1840 Census), assigning new codes for what they perceive to be medical conditions.

Statisically these codes have not often been used in inpatient settings, other than for mental health or alcohol/substance use care.

The revision (to the DSM-III) clearly seems to have been more directed towards protecting the income of psychiatrists and to further their standing in the medical community, than it was towards more effectively treating "patients".

While facilitating claims from insurance companies, to increase affordability of treatment for potential clients. To support more psychiatric and pharmaceutical research. And for approval of pharmaceutical medications by the FDA for so-called mental “illnesses”.

All of the above was set into motion by assigning people with incurable, voted into existence, medical “disorders” that prolong or prevent cure.

On subsequent revisions of the manual, direct ties between members of the task forces with the pharmaceutical industry became glaringly apparent and a major cause for concern.

Why, then, is the DSM still being used by clinicians wanting to actually help people with mental health challenges?

Why are a vast majority of students of psychiatry and psychology (globally) still being given this one book, as a standard text and their "Bible", to diagnose people with these mental health “disorders”?

And does their education include a history of the DSM, in order for them to make an informed decision about what perspective and resultant approach they may prefer to adopt…

to treat (and actually possibly heal) people?

As Jung did with Sabina Nikolayevna Spielrein.

"The Cycle of Classification: DSM-I Through DSM-5"

Jacqueline L. Tilley, K. Blackwell, P. Mortensen Published 2014 Psychology

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24679178

Information on the psychiatric pharmaceutical industry

The U.S. pharmaceutical industry is one of the most profitable industries in the history of the world, averaging a return of 17 percent on revenue over the last quarter century. Drug costs have been the most rapidly rising element in health care spending in recent years. Antidepressant medications rank third in pharmaceutical sales worldwide, with $13.4 billion in sales last year alone. This represents 4.2 percent of all pharmaceutical sales globally. Antipsychotic medications generated $6.5 billion in revenue. 42

I’ll finish off with some thoughts from far more educated and eloquent minds than mine. I’m simply sharing the information I discovered when I took the time to ask some pertinent questions and find out more about how all of this works.

There are many great thinkers in the field of psychology.

Now largely forgotten by an industry that has medicalised these reactions as “disorders” and mental “illnesses”.

An industry that, in 2022, chooses to diagnose chronic psychiatric “illnesses” within first 45 minute sessions and to medicate people (possibly for life) as standard practice…

instead of addressing the primary causes of distress.

Even though there are still many psychiatrists, psychologist, sociologists and even anthropologists who suggest a return to a more traditional perspective on mental health and treatment of these challenges.

Additionally to the concept of mental disorder, some people have argued for a return to the old-fashioned concept of nervous illness. In How Everyone Became Depressed: The Rise and Fall of the Nervous Breakdown (2013), Edward Shorter, a professor of psychiatry and the history of medicine, says: 43

“About half of them are depressed. Or at least that is the diagnosis that they got when they were put on antidepressants. ... There is a term for what they have, and it is a good old-fashioned term that has gone out of use. They have nerves or a nervous illness [my boldface]. It is an illness not just of mind or brain, but a disorder of the entire body... 43

The nervous patients of yesteryear are the depressives of today. That is the bad news.... There is a deeper illness that drives depression and the symptoms of mood. We can call this deeper illness something else, or invent a neologism, but we need to get the discussion off depression and onto this deeper disorder in the brain and body. [my boldface]

— Edward Shorter, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Toronto 43

Citations from page on so-called Mental “Disorder” on the Wikipedia website mentions some concerns of many talented mental health professionals:

Since the 1980s, Paula Caplan has been concerned about the subjectivity of psychiatric diagnosis, and people being arbitrarily "slapped with a psychiatric label." Caplan says because psychiatric diagnosis is unregulated, doctors are not required to spend much time interviewing patients or to seek a second opinion. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders can lead a psychiatrist to focus on narrow checklists of symptoms, with little consideration of what is actually causing the person's problems. So, according to Caplan, getting a psychiatric diagnosis and label often stands in the way of recovery [boldface]. 43

In 2013, psychiatrist Allen Frances wrote a paper entitled ‘The New Crisis of Confidence in Psychiatric Diagnosis”, which said that “psychiatric diagnosis... still relies exclusively on fallible subjective judgments rather than objective biological tests [my boldface].” Frances was also concerned about “unpredictable overdiagnosis.” 43

For many years, marginalized psychiatrists (such as Peter Breggin, Thomas Szasz) and outside critics (such as Stuart A. Kirk) have "been accusing psychiatry of engaging in the systematic medicalization of normality." [my boldface] More recently these concerns have come from insiders who have worked for and promoted the American Psychiatric Association (e.g., Robert Spitzer, [my boldface] Allen Frances). 43

A 2002 editorial in the British Medical Journal warned of inappropriate medicalization leading to disease mongering, where the boundaries of the definition of illnesses are expanded to include personal problems as medical problems or risks of diseases are emphasized to broaden the market for medications. [my boldface]43

Gary Greenberg, a psychoanalyst, in his book "the Book of Woe", argues that mental illness is really about suffering and how the DSM creates diagnostic labels to categorize people's suffering. 43

Indeed, the psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, in his book "the Medicalization of Everyday Life", also argues that what is psychiatric illness, is not always biological in nature (i.e. social problems, poverty, etc.), and may even be a part of the human condition. 43

And my all time favourite:

“I'm not critical of the people who do psychotherapy. The therapists in the trenches have to face an awful lot of the social, political, and economic failures of capitalism. 44

I am attacking the theories of psychotherapy. You don't attack the grunts of Vietnam; you blame the theory behind the war. Nobody who fought in that war was at fault. It was the war itself that was at fault. It's the same thing with psychotherapy. 44

It makes every problem a subjective, inner problem. And that's not where the problems come from. They come from the environment, the cities, the economy, the racism. They come from architecture, school systems, capitalism, exploitation. 44

They come from many places that psychotherapy does not address. 44

Psychotherapy theory turns it all on you: you are the one who is wrong. What I'm trying to say is that, if a kid is having trouble or is discouraged, the problem is not just inside the kid; it's also in the system, the society.” 44

James Hillman

It’s time we asked “why?” again

What if Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and other great minds and forerunners of this discovery into the “whys?” of mental health challenges were right all along?

What if these “disorders” are simply reactions to past experience, current external circumstances and an underlying anxiety (neurosis) because of them?

What if, by helping a person process whatever experiences provoke these reactions and teaching them more positive behaviours, these reactions can be minimized or completely eradicated?

What if life has become infinitely more stressful and most households need dual income just to get by?

What if healing primary root causes of these reactions takes time and people can’t afford to miss work for long periods?

What if treatment options are expensive and state ones are overwhelmed?

What if private medical insurance only pays for three weeks of treatment and the State can only afford the same duration?

What if treatment facilities only have around three weeks to stabilize people, to get them back to work, and proper recovery and healing for these conditions takes time?

What if the quickest way to get people out of treatment and back to work or school is to diagnose an incurable disorder and medicate them with pharmaceuticals?

And the pharmaceutical industry is one of the most lucrative industries in the world?

What if mental health and addiction have become so stigmatized that most people are afraid to even ask these questions or have this conversation?

What if we’ve been led to believe that these are medical conditions and doctors know how to treat medical conditions so we should simply trust their judgment?

What if a vast majority of students of psychiatry and psychology are given one book to refer to in treating mental health challenges and are told it is their “Bible of psychiatry and psychology”?

And the remaining students, globally, are also given this book as additional study material during their education?

And what if the majority of mental health professionals and therapists now also believe mental health challenges are incurable disorders as a result of this?

I went back to the beginning and took the “Psychodynamic” approach to understanding my trauma induced reactions.

I took a different approach to getting well after I understood what a “diagnosis” was supposed to be. And when I began to understand that my (mis)-diagnoses were only a name given to a list of reactions / maladjusted behaviours.

I worked for three tough years to find the root causes of my reactions and focused on recovery for those alone.

I am now four years medication-free with no further support groups, therapists or treatment necessary.

This… when I was repeatedly told, by leading mental health professionals and / or support groups, that I had some kind of disorder (or another), or disease…

and I would need chronic medication or work programs of management for life.

But I only began to make relevant connections to my primary traumas, and progress substantially, when I fully understood what trauma actually is.

And how trauma really “works”.

Free to share and distribute

With thanks to the community on Hive for your courage and open-mindedness and to Internet Archive for your service.

This project would never have been completed without your resources and support.

by the talented Alan Asnen due to his interest in this content.

Thank you for your generosity of spirit, Alan.

I do not endorse the information shared in K.I.S.S - Keep it Simple Sweetheart Perfect to be used in place of professional medical advice, support groups or specific therapies.

Please do not come off any prescribed medication without the guidance and support of a trained professional.

Please do not step away from any programs of treatment or support groups without the guidance and support of a trained professional.