(a note. all my pictures on my posts are my own photography, unless otherwise noted. In this case, the the drawings featured are from Wikipedia Creative Commons. For podcast episodes, I use photos given to me to use by permission from the guest)

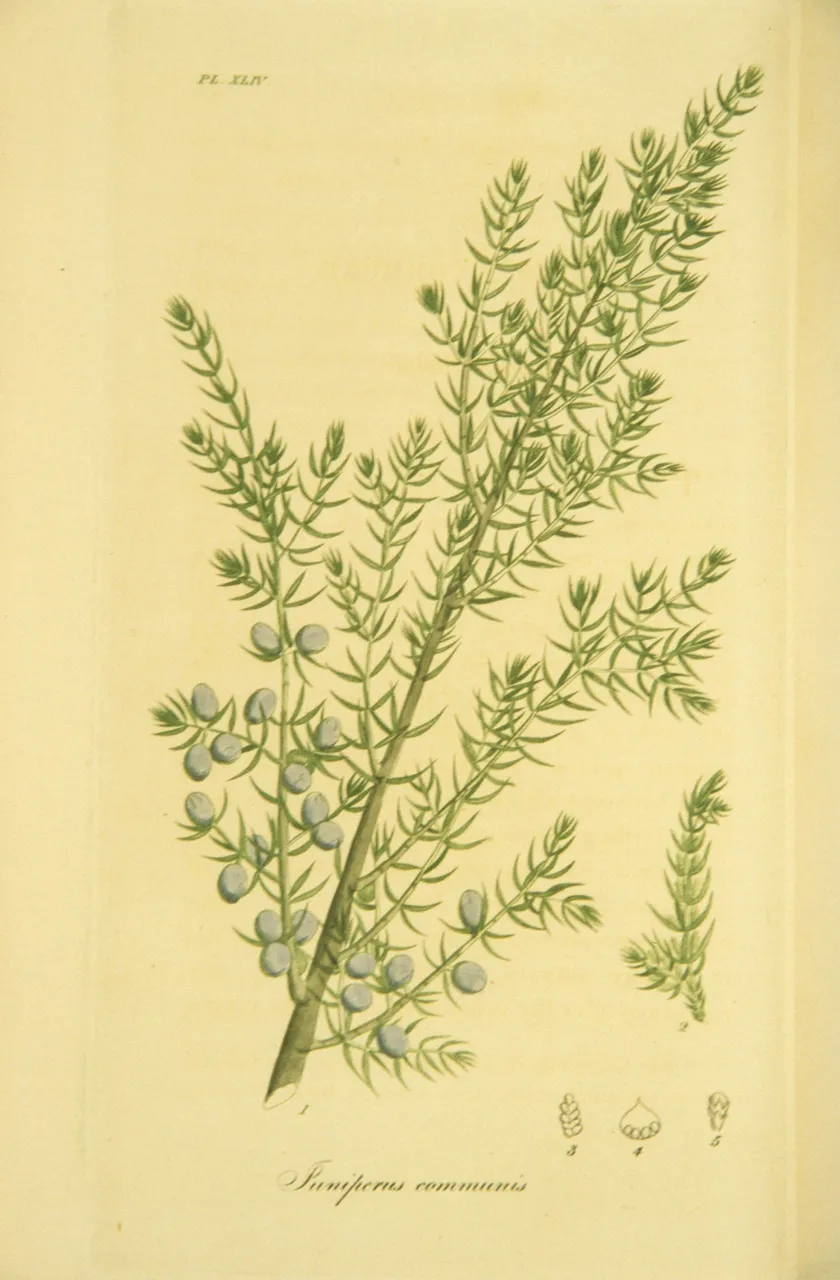

Juniperus communis

Common Juniper / Ground Juniper

Baie de Genévrier

- Juniperus communis is the species of Juniper that stays small and low growing. It is a species of Juniper found abundantly throughout the world, perhaps most so out of any woody shrub, and perhaps of any conifer (Enescu). It is found mostly in northern areas, but is also scattered into the southwest, and all across Europe, parts of the Middle East, the Himalayas and other parts of Asia, Russia and Japan.

Its use historically in medicine traditions follows this range, and curiously, many of these ways of using Juniper are similar, yet also obviously culturally unique to each people and place.

As I mentioned earlier, Junipers have different leaf forms, some needled, some scaled. Usually younger plants have needled leaf forms, and as the plant gets older the leaves scale up (but not always). This species of Juniper tends to stay in needle form, growing in whorls of three. There is also a white band found on the top of each needle. Again, it also tends to grow as a low shrub and not so often a large tree. It can be found in the vast boreal open lands where larger trees are not present, or under trees in conifer forests. It will find its way into the crevices of rocks, surrounded by lichens, mosses and cryptobiotic soils.

This species is very abundant overall, but in certain localities where human populations are high and use of the plant is high as well, the populations are in decline.

According to Gin Foundry:

…In Britain there has been a substantial decline in both the distribution of juniper and the size of juniper colonies, particularly in England.

It is used as an ornamental all over the world for its low, shrubby appearance and resilient nature, and can be found in front of all matter of landscaped buildings or homes.

Because of the wide geographic range of Juniperus communis, it is incredibly variable and has many subspecies or variations. It thrives in harsh environments and full sun. It is considered a pioneer species, like Juniperus virginiana, growing in places first before anything else is able to. This species of Juniper also hosts ‘rusts’ in Europe like Gymnosporangium clavariiforme.

According to ‘Conifers of California’ (Lanner), it even grows up at high elevations above 11,000 feet, alongside the ancient Bristlecone Pines.

Juniperus osteosperma or utahensis

Utah Juniper

Hunuvu (Owens Valley Paiute)

Wa’ap, Wha-Pee (Southern Paiute)

Sahwavi (Shoshone)

- Utah Juniper is usually found growing with Piñon Pine, especially the single-needled variety. My plant write up on Piñon can be found, here. It is most known for its predominance in the Piñon Juniper woodland of the Great Basin Desert, but its range also extends into other deserts and ecologies to the north and south of the Great Basin. Like other Juniper species, it can thrive in harsh environments, and quite possibly prefers those habitats.

Utah Juniper is different from other Junipers in a couple ways. It had larger 'berry-esque’ seed cones, and actually tends to be monecious (multiple sexes on one plant) rather than dioecious (different sexes on different plants) most of the time. Birds, jackrabbits, coyotes and humans eat the ‘fruits.’ The wood, like other Juniper species has usually been used by humans where the plant grows; as carved items useful for everyday life or as fence posts resistant to rot. Like other Junipers, it dies in fire.

Due to the Pine Bark Beetle (and other pests) killing millions of Pines of different species across the West, Juniper species are thriving in the wake of dead trees. The proliferation of this beetle is largely due to rising global temperatures, drought and shorter winters. This beetle is a native species. Here’s an article on the beetle, which I highly recommend reading up on and being aware of when engaging the Piñon Juniper woodlands of the west.

Utah Juniper is often demonized for being ‘invasive’ in the Great Basin Desert, its primary home. This is due to a complexity of political and ecological reasons. Previously, Piñon Juniper woodland was heavily logged in Nevada for ore smelting. Often European ancestored settlers historically saw deserts as ‘no man’s land’ and a desolate place without value. Much of the old accounts and literature use this language to speak about the landscapes, and even old European maps skip over vast deserts in their orientations of place, or don’t know how to spatially understand them. Our ability to abuse deserts in part has to do with the fact that we believe culturally that there is no life in them, and that they are no important. This is certainly untrue. As Piñon Juniper woodlands grow back from a period of heavy logging, and into an era of heavy ranching (also seen as the only ‘useful’ thing to do with this land), the woodlands are seen as encroaching Sage Ground habitat. Juniper has always moved with changing climates and doesn’t have one set baseline for where its is supposed to permanently grow. Juniper thrives in harsh and heat, and so will thrive in a warming climate. Often Sagebrush step ecology is intertwined with Piñon Juniper woodland and the two ecosystems exist together. The Piñon Juniper are not trying to push out Sagebrush, they are no in competition. The Sage Grouse even use the trees for protection and mating rituals, though ecologies and ranchers claim the trees provide more habitat for Sage Grouse predators. In reality, mining and ranching do way more damage in the Great Basin than Junipers supposedly encroaching on Sagebrush. These trees don’t benefit ranchers who want the land to be open for cows and who want to plant non-native annual grasses for quick beef turnover.

In the Works Cited at the end of this article, I include links to news articles about Juniper being ‘invasive’ and about the Piñon Juniper woodland, a native ecosystem, being an ‘enemy.’

Juniper medicine

- There’s a lot to say about Juniper as a food, medicine and tool, and I know I’ve explored the tendrils of this plant pretty deeply thus far, and some of its interweaving with humans. The significance of Juniper culturally and ecologically on a global scale cannot be ignored. Again, it is important to note the similarities in how it is used in different locations around the world. Its use for fire, craft, food, medicine, protection, and cleansing no matter the species and location seems to be universal, even if the methods, stories vary.

Juniper is a powerful anti-fungal. The leaves, branches or berries as a wash can help with fungal infections on the skin. Infused in vinegar, and used to clean a moldy house (a common problem in humid places in the summertime) it can kick back black mold that is harmful to human health. It is also used in making containers, ‘cedar’ chests, which can inhibit mold on clothing, or keep bugs out. They also tend to last a long time!

Juniper berries and twigs are diuretic. Juniper is also antibacterial, so it’s use for UTI’s is logical. It helps the body to push out bad bacteria while also killing back that bad bacteria. I’ve used the berries for that purpose— but I would suggest also pairing it with a powerful berberine-containing plant (Barberry, Oregon Grape before Goldenseal or Goldthread if possible) and an appropriate Heath family plant (Blueberry leaf, Manzanita leaf, Cranberry fruit, Uva-Ursi leaf) for further flushing. Tea is best as alcohol is irritating to the kidneys, bladder and urinary tract especially during an infection- but I have taken a mild tincture of the plant in hot tea made with the said plants and feel like double timing it was a powerful way to knock the UTI out. I would be careful with using Juniper berries once the infection has gone to the kidneys. Have antibiotics nearby and a doctor to consult as UTI’s are nothing to mess with. I would limit internal use of Juniper leaves, and stick to topical use.

I would stay away from Juniper berries and leaves internally during pregnancy especially, as multiple cultures view Juniper as an abortifacient.

Juniper berries are bitter and act on the bitter receptors, increasing digestive capacities of the body. They also stimulate appetite. The scientific research on the actions of Junipers match up to the thousands of years of traditional use around the world. According to the American Botanical Council’s citations of the German Commission E research on Juniper:

The Commission E approved the use of juniper berry for dyspepsia. [indigestion]

As I have mentioned in other plant profiles, the German Commission E was a paid for scientific research project done by the German government to investigate the medicinal qualities of popular folks herbal remedies in Europe. Most of the research ‘proved’ the common uses of the plant as true. Unfortunately, some of this research was done on animals.

While a tea of the young twigs or berries is helpful for UTI’s and increased digestive function, Juniper can also be used in conjunction with other immune supporting plants for colds and stomach upsets. Cross-culturally, Juniper branches and berries have been used in times of sickness- as a wrap on the body, or as a strong tea.

The berries are used as a food and spice for flavoring. I mention different ways this has been the case below in more detail.

Burning Juniper can cleanse the air energetically and physically.

A note on Juniper magic and considering the lens of settler-colonialism

- Juniper is perhaps first and foremost known for ‘protective’ abilities spiritually, energetically and physically. Whenever working with plants that offer ‘magic’ or protection in the human world, I sit back and think about all of the ways we interpret what magic is from a western perspective informed by the settler-colonialism narrative.

I formerly studied Philosophy and Anthropology, and these questions were always on my mind: firstly- why is it that there are mostly white men studying mostly brown people? Other questions I had: Why was language of the ‘civilized’ vs. ‘uncivilized’ used when talking about ‘other’ cultures which were under study? Did these people actually give consent to being studied, observed and imposed upon by an outside white male looking to be the ‘discoverer’? Why do anthropologists hide in their writings the actual magic and ‘supernatural’ they really witnessed?

Anthropology and perhaps even its branching out into Ethnobotany which is what I primarily work with in my writings; is inherently flawed as a ‘field of study’ because it is assumed that the lens from which to look at the human world in relationship to the natural world must be seen from a western scientific perspective. This assumes that all ‘magic’ must be explained away scientifically, or else one cannot be taken seriously aka. ‘the Carlos Castaneda effect.’ Anthropology was basically a field focused on ‘preserving’ ‘primitive’ cultures by observing them and making notes before the western world wiped them out, thereby museum-ifying real human beings and their way of life.

At the same time, magic is now ‘cool’ and the appropriation of symbols and rituals of magic from cultures that have been dominated over in settler-colonialism aka ‘western thought’ is rampant. This seems like an endless kind of watering down of whatever western thought sees as more authentic than itself. SO while magic isn’t taken seriously in the academic world, rain dances are just merely a ‘dance’ nothing more; magic is also bought and sold by the predominately white-skinned western world on a kind of surface level, more now that ever. And for a lot of money. The complexity of who owns what cultural symbols, traditions, clothing, and practices perhaps makes it a difficult conversation to have. And, how also ‘holding in time’ the ‘idea’ of cultures without allowing them to change and morph and express whatever version of what they want into the world is also a form of settler-colonialism.

When I was studying Philosophy and Anthropology in a formal academic setting, one of my most treasured teachers (among many) was the late Mai Lan Gustaffson, a half-Vietnamese woman, who essentially challenged the mainstream field of anthropology by writing a book on magic and ghosts with real evidence of their connection and importance in her book War and Shadows: the Haunting of Vietnam. She essentially cites how the trauma of war and genocide and the loss of specific cultural death rituals to a oppressive regime that didn’t allow them, increased the occurrences of hauntings and supernatural disturbances in Vietnam due to unsettled spirits, and the unresolved grief of the living. I took a class with her that was actually called ‘Magic, Witchcraft and the Supernatural’ or something like that - where she basically spent the whole semester completely challenging our western brainwashing on how we explain away or dismiss magic based on the fact that ultimately the western world sees itself as culturally superior. And in an age of massively increased globalization (which was my main topic of interest in formal schooling), the effect of the superiority complex of ‘western thought and culture’ bleeds into everything- also called by some globalization writers as ‘McDonaldization.’ This also goes for thinking about, writing about, and working with plants, and also our relationship to capitalism and plants. The late Dr. Gustaffson basically instilled in me the idea that we should pay close attention to our biases and filters. Even the late Michael Moore states in ‘Medicinal Plants of the Desert and Canyon West when talking about the universal magic of Juniper:’

The aromatic properties of all parts of Juniper have been used against bad magic, plague, and various negative influences in so many cultures from the Letts to the Chinese to the Pueblo Indians that there would seem to be some validity to considering the scent as beneficial in general to the human predicament. Overlapping traditions are useful in triangulating valid functions in folk medicine. (65)

It is even ridiculous that ‘triangulating’ cultural uses of plants that grow in different locations is even necessary to ‘prove’ the magical or even physical medicinal properties of those plants or group of plants.

So, the point of all of this? To offer another seed to think about the importance of considering magic real, and to also be careful how we use this magic, and that we do not do harm to those who have not been able to practice it freely.

Juniper has been considered magical and protective via it’s smoke through burning the leaves and branches all over the world where it grows, including in Europe and northern Europe which has a complicated history onto itself of brutally erasing the magic of its own land-dwelling inhabitants. It has been made into incense for fumigating spaces to ‘cleanse’ them physically and energetically. Even the hanging of Juniper branches in spaces, above doors, on the walls, helps to protect the space from people or spirits with bad intentions. Juniper is a plant of boundaries, and there is no denying, even with all the ‘triangulating’ aside, that it simply works. Try burning a sprig of Juniper and smelling it, or hitting the branch against your legs or feet- the practice of feeling into the experience of its ability to work with boundaries is the best way to know magic is real.

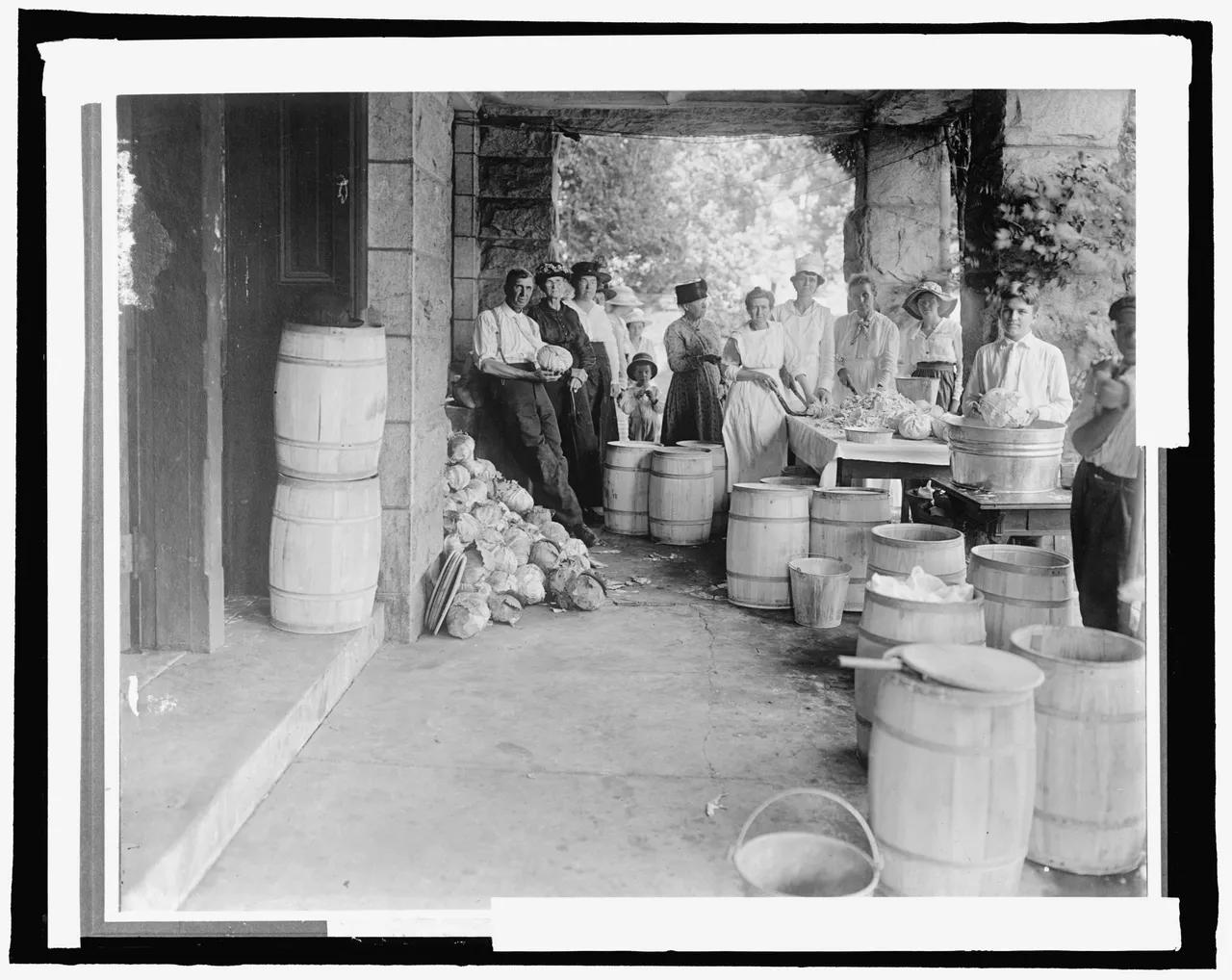

(Kraut making with Juniper and Cabbage, old photo from Wikicommons)

Europe/Scandinavia:

- J. communius is the main species that grows in Europe and Scandinavia. It is used in cooking food, preserving and pickling vegetables. Its method of use varies in Europe, and is often associated with sauerkraut as an added flavoring and preservative element. Sauerkraut is a ferment using cabbage, salt and spices — originally from China and originally using rice wine — and is more often associated with Germany and other parts of Europe. Juniper has some Vitamin C in it, and so does fermented Cabbage, and the combination together makes for a great winter food to incorporate in the diet.

Juniperus sabina, or Savin Juniper, grows primarily in Europe. This species is considered poisonous.

Then there’s Gin, which originated in Holland.

Gin is an alcoholic spirit that most folks recognize as a favorite ingredient in slightly bitter, sometimes citrusy mixed drinks. The word ‘Gin’ is derived from the word Juniper and it is the primary herbal ingredient. It is also required that anything labeled and sold as Gin currently must have a certain percentage of Juniper berries in it. Flavors vary according to location of the Juniper plant. Different soil and climate conditions can affect the flavoring of Juniper berries in Gin.

According to the Gin Foundry:

Juniper berries are primarily used dried as opposed to fresh in gin production, but their flavour and odour is at their strongest immediately after harvest and declines during the drying process and subsequent storage.

Often it is distilled with the young branches as a strainer and the ‘berries’ lightly crushed as the main component. Traditionally J. communius was used, and is still used to make Gin in Europe. It seems like Juniper’s use in brewing is universal in Europe. There’s a lot to say about how the use of plants like Juniper in things like alcohol spread from one location to another— and morph and shift according to environment and culture. Here’s an interesting article on the matter, here.

Folks are currently branching out experimenting with using other species of Juniper in North America and beyond. It certainly makes sense to use the plant in the place where you are brewing if possible. Given the abundance of Juniper in the western U.S., it seems obvious to use a local variety. Talking to a friend who lives in New Mexico, she said that the local Gin distillery imports their berries from Europe though Juniper grows all around because they are afraid the local variety is poisonous. Each Juniper can impart different flavors, and some can be quite bitter. Gin is often used in bitters drinks: cocktails combining some amount of bitter herbs infused in sugar, honey, alcohol, glycerin, vinegar or some combination thereof and taken before or after a meal with added tonic water to increase the efficiency of digestion. These can be called Apéritif (before the meal) and Digestifs (after the meal). There are lots of plants out there used in Apéritifs or Digestifs and that would be a whole other writeup! There are also other drinks made in different parts of Europe like ferments and soft drinks that contain Juniper. Savin and Genvrette are two examples.

Juniper is used in the traditional sauna as well as in bathhouses alongside plants like Birch in the form of small brooms used to gently hit the body, creating heat and releasing oils from the plants.

Sandor Katz mentions a traditional Juniper soda in his big ‘The Art of Fermentation’ book, and has a recipe for making it.

To be continued... I know this is long and I'm a geek! I've been working on this for years while traveling and studying the trees in the field, and just updated it again this winter. I've got a little more written up about Juniper in Asia and the U.S. that I will share another time.

(I will be including my Works Cited and book resources in the last post I do on Juniper)

follow me on instagram @goldenberries / listen to my podcast at Ground Shots Podcast