Today I’m deviating way out of my comfort zone. I usually post about interesting science findings in molecular biology, but I recently spent a weekend with a social psychologist. He told me all about what it’s like to work in that field and suggested I write a post about a social psychology paper. I figured it’d be a great opportunity for me to get acquainted with an area of study that I’m not too familiar with so I accepted the challenge. He recommended I check out the paper “Can We Undo Our First Impressions? The Role of Reinterpretation in Reversing Implicit Evaluations” written by Thomas C. Mann and Melissa J. Ferguson (1) and, after a quick read, I agreed that it was definitely worthy of an in-depth review.

The Trouble with First Impressions

The goal of this paper is to try to understand how the first impressions a person might develop can be altered. First impressions are notoriously difficult to change. This is often taken for granted as no one really questions popular sayings like “you never get a second chance to make a first impression” or “your first impression is your last impression.” However, this common assumption has been backed up by real data as well. It turns out that once a person has developed an impression about someone or something, it can be difficult to change their mind even when presented with compelling facts (2).

This work is important because inaccurate first impressions can lead to some of the worst aspects of society. It’s part of the reason why racism, bigotry and xenophobia continue to persist in this world. If we ever hope to rid our society of these problems, we need to know how to change first impressions.

Implicit vs explicit evaluations

Studying first impressions can be difficult and the authors explain why by discussing the differences between implicit and explicit evaluations:

Explicit evaluation: This refers to an intentionally communicated opinion by an individual. For example, John Everyman vocally agreeing that he like astronauts is an explicit evaluation.

Implicit evaluation: This is how the individual might feel, either consciously or subconsciously, about something without intentionally communicating it. For example, even though John says he likes astronauts, he gets a bad feeling in the pit of his stomach when he sees one because he caught Buzz Aldrin having sex with his wife.

Studies have shown that while explicit evaluations are relatively easy to change, implicit evaluations are not (5). They tend to stick with an individual even when they learn their initial impression is false Thus, the authors want to make sure that they can change both the explicit and implicit evaluation an individual has after a first impression.

Measuring implicit evaluation

The trouble with studying first impressions is that while implicit evaluations are needed to fully understand how an individual truly feels, but are difficult to measure. After all they are, by definition, unintentional. However, past studies have validated a fairly effective method called the affect misattribution procedure (6). In brief, the experimenters show the participant an image of a person or thing, then an image of a random pictograph (eg a Chinese ideogram). Afterwards, they ask the participant whether the pictograph has a good or bad meaning.

An example of the affect misattribution procedure.

Multiple studies have shown that the participant’s evaluation of the pictograph is influenced by their implicit evaluation of the preceding image. The pictograph tends to be rated positively if they like the person or thing in the image and negatively if they do not.

Using Reinterpretation to change an impression

The unique hook of this paper is that the authors tried a novel method for changing a first impression called reinterpretation. Most previous studies have tried to alter an implicit evaluation by either adding new unrelated information or by subtracting the information from the initial impression (2). If we go back to John E. and his complicated relationships with astronauts, an example of addition would be if Buzz Aldrin gave John $1,000,000 to apologize for his cuckolding ways while an example of subtraction would be if John only dreamed that his wife was getting it on with a real astronaut. In both cases John should have ample reasons to like astronauts now, but studies suggest that his implicit evaluation wouldn’t change. In other words, neither addition nor subtraction has been shown to be effective at changing an implicit evaluation by itself. The authors considered these previous attempts and decided to try reinterpretation instead. In reinterpretation, information is provided that encourages the individual to revise their initial impression. It can almost be thought as a combination of both addition and subtraction as the extra information provided is meant to overwrite the original impression. In our John/astronaut scenario, and example of reinterpretation would be if John found out that Buzz Aldrin was actually giving his wife CPR, thereby saving her life.

The experimental setup

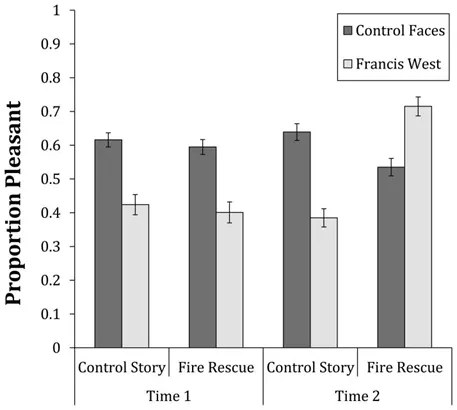

In order to create a reinterpretation scenario, the authors told participants a story in which a man (Francis West) is, depicted breaking into houses, followed by the revelation that he was trying to save children inside from a fire. They used the affect misattribution procedure (described above) to determine the implicit evaluation of participants to Francis West both before and after the revealing statement. In order to use the proper controls, half the participants were given a control story that lacked the reinterpretation statement, and all participants performed the affect misattribution procedure on control faces in addition to Francis West. Their results are shown below:

Proportion of ideographs judged more pleasant than average in the experiment described above.

The y-axis labeled proportion pleasant shows the proportion of participants that had a positive reaction to the pictograph and is the measure of their implicit evaluation of the individual. As you can see, most participants had a negative opinion of Francis West before the revealing statement (time 1) and after the non-revealing statement (control story, time 2). However, if audiences were given the reinterpretation statement, their implicit evaluation of Francis West changed dramatically. It went from a net negative to a net positive. This was a great finding for the authors as it essentially confirmed their hypothesis that reinterpretation can alter an implicit evaluation.

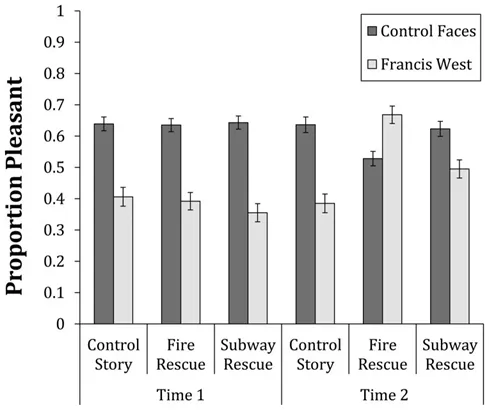

Despite this accomplishment, the authors still needed to confirm that reinterpretation was more effective than other methods of changing an implicit evaluation. They decided to expand the current experiment by testing participants with a statement that adds information about Francis West without causing reinterpretation. This statement informed the participants that Francis West once saved a baby from an oncoming subway which was judged by an independent survey to be just as “good” as saving children from a fire. The results of this experiment are below.

Proportion of ideographs judged more pleasant than average in the experiment that included a potential subway rescue story.

As you can see, the “subway rescue” story slightly improved the participant’s implicit evaluation of Francis West, but the effect was not nearly as dramatic as that of the reinterpretation “fire rescue” statement. Thus, reinterpretation is more effective than previous methods of changing an implicit evaluation or first impression.

After these initial tests, the authors began further delving into this phenomenon in several different ways. They showed that this change in implicit evaluation is lasting, and is enhanced when it is emphasized that this new information changes the meaning of the original story. They also show that the effect is lessened when participants are required to memorize a long number. However, the main takeaway from the articles is still within the first series of experiments: The authors have found that reinterpretation can change an implicit evaluation better than previous methods.

Overall I was quite impressed by this work. The goal of the paper was clearly stated and I am convinced that they achieved it. My main complaint is that they didn’t show reinterpretation to be more effective than subtraction. It would have been nice to see what the implicit evaluation of Francis West would have been if participants were told the story was false. Another small quibble I had was the the name “Francis West” is very close to the protagonist of Dead Rising, Frank West, and I really wanted to play that game while reading the paper. However, these complaints are fairly minor and don’t call into question the main conclusions of the paper. Furthermore, these conclusions provide a viable method for changing first impressions by undermining the basis of those impressions. Hopefully, we can leverage these findings to help reduce racism, xenophobia, and other awful implicit evaluations in today’s society.

References

(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4437854/

(2) https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/114/1/37/1921740

(3) http://melissaferguson.squarespace.com/research/#ideology

(4)

(5) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16910748

(6) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/spc3.12148/abstract

About the Author: I’m a research currently living near Boston. I recently left academia to work in in industry, but I miss teaching so I decided to start writing articles on interesting discoveries in the world of microbiology. My goal is to uncover subjects that are unusual, unique, and might one day have a major impact on our daily lives. If you like this work, please consider giving me a follow: @tking77798

SteemSTEM

I’ve decided to start putting my support behind the @steemstem project and I encourage you to do the same. SteemSTEM is a community driven project which seeks to promote well written/informative Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics postings on Steemit. The project not only curates STEM posts on the platform through both voting and resteeming, but also re-distributes curation rewards as STEEM Power, to members of Steemit's growing scientific/tech community.

To learn more about the project please join us on steemit.chat (https://steemit.chat/channel/steemSTEM), we are always looking for people who want to help in our quest to increase the quality of STEM (and health) posts on our growing platform, and would love to hear from you!