Some people asked about my scientific background and that inspired me to write this post, in which I will share how I got interested in science in the first place and the steps that brought me to where I am today. Maybe it might serve as an inspiration for those who would like to kindle the love for Science in their children, siblings or family members, as well as those who are considering making a career as a natural science researcher – perhaps you are just curious to know what the path towards becoming a scientist is like!

As I had mentioned already in my previous article “Ever wondered what pursuing a career in science is like?” my interest in Science was fostered by my parents and my grandfather since I was a kid.

Even though neither of them works in the field nowadays, both my parents studied Biology. Therefore, in my home, talk about the natural world, genetics and science was always present.

My parents had a very nice collection of books about natural science; these books had big, glossy pages with amazing photographs and illustrations. Since I was very little (we are talking about 5-6 years old), one of my preferred ways of entertainment was looking through them. I was mostly looking at the pictures, but whenever I stumbled upon one I found interesting, I would read the caption and learn something.

My favorites were Cosmos by Carl Sagan, one about evolution and another about genetics. So, from a very early age, I learned about Mendel’s experiments with pea plants and how he discovered the laws of genetic inheritance, about Darwin’s trips to the Galapagos Islands, and how our planet Earth was just a tiny blue dot in the immensity of the universe.

I was fortunate to have parents who were very patient with me when it came to giving me explanations about the world around us and the way it works. They would always have a good disposition to show me things or discuss any questions I had or to provide me with materials that could help me learn what I wanted. My grandfather was the same, and along with my parents would frequently buy me science books and magazines designed for children. These books and magazines usually had a variety of experiments that you could perform with simple household items and served as a demonstration of some scientific principle.

This was a great way to learn science because by doing the experiment yourself, you could witness the result with your own eyes and also keep it in your mind in a more significant way than just reading about it in a book, because now you actually had created a fun and/or enjoyable memory about it!

One of these children’s magazines that I really loved was called “Chispa” (which means “Spark” in Spanish). It had the perfect mix of content to be really interesting for kids: short articles about some interesting fact of nature, kid-friendly introductions to scientific principles like diffraction of light, the effect of gravity and why eclipses occur, as well as fantasy/adventure short stories, comic strips and other entertaining features–I remember one about a chocolate factory, that showed how cherry-filled chocolates (my favorites!) are made.

On top of that, since I was already a mini-nerd by age 9-10, whenever there would be a chance to get a gift (for Christmas, my birthday, etc.), I would ask my parents for one of those chemistry experimental sets designed for kids and spend my afternoons performing the experiments suggested in them:

What all these resources had in common was that they didn’t make Science seem like a distant and complicated thing, but something that we could observe in our everyday life and play with – something we could get involved in and spend some time exploring and experimenting with. I believe this kind of early involvement is crucial to learn to become familiar with science and demystify scientific work.

Instead of looking at scientific work as some incredibly complicated, tedious and secretive enterprise, you start to realize that it is something that anyone could try and take part in. That is, you can train to become a scientist and make your own discoveries about the world if you want, isn’t that an amazing thought?

My high school years, and the inception of my scientific vocation.

Thanks to the early start I talked about above, Biology was always one of the subjects I enjoyed the most and excelled at during my school days. At age fifteen, I started competing in the Biology Olympiad, at first on the regional level, then state-level and finally at national level.

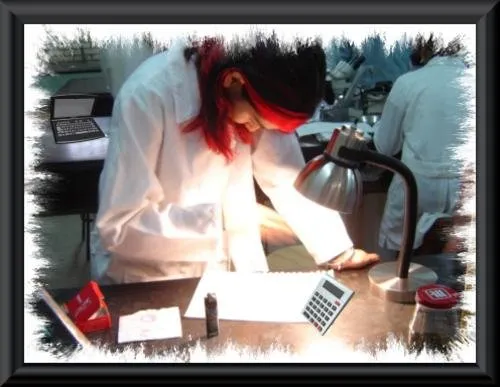

The Biology Olympiad is a knowledge-based competition in the field of Biological sciences, consisting of a theoretical exam and a practical one where you perform experiments and then analyze the data obtained. I did a lot of studying to prepare for it on top of my regular school activities. I noticed that the subjects that I enjoyed learning the most about, and that felt effortless to study, were genetics and molecular biology (with ecology, plant physiology and biostatistics being the ones that I abhorred the most).

One day my grandfather, as he used to do from time to time, sent me a copy of an article he found interesting for me to read. It was an article about genetic engineering. It had such an impact in me that I remember the exact moment when I read it: in my High school’s library, sitting on a little table facing the main desk, with some sunlight softly shining through the window.

I remember thinking it was the coolest thing I had ever heard of: using incredibly clever mechanisms, scientists could cut out little pieces of DNA using some sort of “molecular scissors” and then insert the pieces somewhere else – even in an entire different organism! In this way, they could confer new characteristics to the modified plant or animal that under natural circumstances it would never be able to possess: you could make such organisms glow, make them resistant to drugs or poison, but most importantly, this held the potential to cut defective genes and replace them with functional ones, which could cure many diseases.

It was then that I decided that I would train to become a natural scientist. More specifically, I wanted to become a Molecular Biologist, doing something related to genetics.

University: doing my time on my way to becoming a scientist.

Honestly, my University experience was somewhat underwhelming. Thanks to all my hard high school nerding to compete in the Biology Olympiad, I already knew the basics of a lot of the content I was taught in the classes.

On top, since I studied general Biology as a career, I had to deal with lots of other stuff I couldn’t care less about like the life and adventures of placton, an in-depth look into the anatomy and physiology of lower Embriophyta (which in case you don’t know, are the least exciting plants in the universe) and let’s not forget about my most abhorred subject EVER: Edaphology, or the study of soil. I can tell you there are very few things in life less exciting than sitting in a lab looking at a bunch of dirt.

For the most part, as one of my classmates put it, university more or less felt to me like “High school, part 2”.

However, there were also amazing subjects with great teachers that were fascinating and I learned a lot from, like Mathematical models (applied to Biology), Evolution, Genetics, Ethnobotany and one that I discovered just then but helped me shape my current way of thinking: Philosophy of Science.

Things start getting serious, a taste of what being a Scientist is really like: Master’s degree

After doing a summer stay in a laboratory that was part of one of Mexico’s biggest and most important research institutes, I decided I would like to do my master’s work there. Said lab specialized in programmed cell death occurring naturally during the development of mammals (when an embryo is developing, some cells must die to “sculpt” the fully formed organism that will be birthed afterwards), while also covering some topics related to how to exploit these programmed cell death mechanisms to get rid of cancer tumors, which was my area of interest.

To get into the master’s degree program offered at this institute, I had to undergo a three-hour long examination test along with the other candidates (I reckon there were about a hundred), and only the top 25 scores would be accepted as students in this very prestigious program.

I immediately felt a huge jump up in academic level as I started my master’s degree. While in my state university most of the people seemed to be there just to pass the time, here my entire group was conformed of highly intelligent, highly focused, hardworking individuals. For the first time in my life it was very evident I was no longer the “star” student, but just one of many –plus it was undeniable that there were people that were much smarter and better prepared than I was– which certainly was a though blow for my ego back then.

The work schedule was exhausting, starting with a non-stop block of intensive lessons from 8:00 AM to 12:00 PM every day, followed by lab work that usually ended any time between 6:00 and 8:00 PM. Basically we lived in the institute, which didn’t feel like such a waste since the city it was in (not my hometown!) was actually quite boring and not very inspiring.

Then I started to do my first “real” scientific experiments; I tasted my first small victories, but also quickly became acquainted with the large amounts of frustration that one has to deal with as a scientist: experiments that don’t work or get ruined, little overlooked details that can have catastrophic effects in your results, finding out that what you thought was wrong all along and now you have to start over… the struggle is real, and your patience and resilience will be tested. Add to that a pinch of crushing pressure from your boss to actually make your project work since they have grants that they have to secure and sponsors they need to respond to, and you will find yourself pulling your hair for days on end.

Even though it was incredibly tough at some points, I really learned a lot, and in the end I managed to get some results that were good enough to form part of a coherent scientific story in my lab, writing my thesis and using my master’s work as a presentation card for future recruiters.

A bittersweet experience: My PhD in Molecular Biology.

Getting the PhD position that I currently have took a lot of work. During my master’s degree I had the chance to do a three month-long research stay at the Max Plank Institute in Berlin, and as a result I made it my ambition to go back and live there in such an amazing city that hosted such amazing science. I started sending lots of applications to different labs but no one would take me (often they wouldn’t reply at all).

Then I applied for an international PhD program in one of the most important institutes for molecular biology and biotechnology in Berlin; I had to do it twice, the first time I was not selected, and the second I managed to secure my place in the program.

Said PhD program was incredibly competitive. The second time I applied, we were told that they received more than 800 applications from potential students all over the world. From those, they selected about 50 people to fly them into Berlin for personal interviews. Then, after the selection process which included presentations of our master’s work and discussions with the group leaders we were interested in working with, about 20 people were successfully accepted as part of the program.

My PhD project pretty much seemed like a dream come true: it was within the field of cancer research, with a potential direct application to finding more effective therapies for patients. The hypothesis was exciting and very clever, groundbreaking stuff. On top of that, I would carry it out in one of the biggest and most prestigious groups in the institute, that seemed to have unlimited budget. I couldn’t wait to start.

As time progressed, it became clear that this project was an enormous task that required constant troubleshooting, re-analyzing and discussion with other experts in the area. To make a long story short, the great complexity of the project –both conceptually and technically–was not evident to me in the beginning, but clearly manifested a couple of years in. It felt really overwhelming at times, and I was doing something different to most other people in the lab so I had no immediate guidance.

Unlike other PhD students, I was not under the supervision of a Postdoc for my everyday work, but had to work independently and certainly many times felt like, despite my monthly meetings with my boss, I was on my own. I had to figure out by myself why things were not working and somehow come up with a way to fix them.

At some point, my PhD life started to resemble the famous “Bad Project” parody video much more than I would like to admit:

In spite of the project dragging out for way too long due to such difficulties, in the end I managed to get some good results that were enough for my committee and supervisor to deliberate that my work could be considered “completed”. So, currently I am in the process of finishing my dissertation so I can finally start the graduation process to obtain my degree – and become Dr. Irime (yaaaaaaay!)

Not everything was gloom and doom, tough, through my PhD I had the opportunity to meet lots of amazing people, learn about incredible science that I didn’t even know existed, and constantly get intellectually stimulated and challenged. I also had the opportunity to travel frequently to many different destinations around the world, and was able to accrue some experience communicating my science to others… which brings me to my final point:

What is next?

After all these experiences, one thing is very clear for me: I love science, and I still find it fascinating and impressive as I did in the beginning. However, I can say with confidence that experimental research is not for me; if I can avoid it, I don’t want to ever hold a pipette in my hand again. The manual labor is tedious, exhausting and frustrating. I like the ideas, but I don’t enjoy the process of production of raw data.

During my PhD, I noticed that I enjoyed doing talks about my project. People responded well to my talks, and many times they would approach me after and give me very positive feedback about my performance. Same with the writing, people seem to find it clear, precise and enjoyable.

I always try to be clear and strive to not make things boring; in contrast, I have no patience for terrible speakers who manage to turn an interesting science project into a coma-inducing snorefest through ill-prepared and poorly delivered presentations. I make an effort to present complex topics in a clear and understandable way, be it in oral or written form. Looking at the state of things around us, it is clear that science communication to the general public is an aspect that is sorely needed. Thus, this is the direction in which I would like to steer my scientific career.

Epilogue

People fear what they don’t understand, and sometimes when I read about how people think about us scientists like some sort of robot-like pragmatic and reclusive machines who are paid tons of money by secret government institutions in order to produce intimidating-sounding research, I can’t help but chuckle a bit.

If only they saw us, wearing jeans and band t-shirts, talking nonsense with each other to pass the time during a tedious experiment, or stalking the conference room to see if we can score some leftover coffee and cookies… Then the revelation will ensue: Oh.my.God… Scientists are just people, like us! Shocking, I know. But also true.

We are not out there to get you, we just have interests that most of the population decided to deem as nerdy. This is not to say that there is not manipulation, ulterior motives or conflicts of interest sometimes happening within the scientific environment: science is an activity conducted by humans, and as such is vulnerable to corruption.

However, despite all of its flaws and shortcomings, just by looking around us we can undoubtedly recognize that science works. Not only it allows us to understand the world, but also to use its natural laws and principles to our benefit.

Despite our differences in points of view, I think I can safely say that we–the big majority of people in this world–are all united in our intention towards making this world a better place and improve everyone’s quality of living. Let’s work towards an open dialogue, fruitful discussions and a better understanding.

-----------------------------------------------------

Image sources not stated above: Book covers from Amazon, Children's chemistry sets from here, Beakman's world pic found on Pinterest (original source unknown).