Genetic Engineering - Building The Perfect Human

What would you give to have perfect eyesight, a faster metabolism, to be a few inches taller or more muscular? For most of history we've had to deal with the genetic hand we've been dealt, and a lot of times that's not much fun. Genetic disorders diseases and inadequacies have plagued our species for thousands of years. But what if we could change all that? The answer may be closer than we think!

After a quarter of a million years of slow natural evolution humanity's on the cusp of having the ability to edit the very building blocks of our being in the past few decades. We've developed tools that help doctors and expecting parents to anticipate any serious health conditions their child may have, such as hereditary diseases and Down syndrome. To

some people these tests already raise ethical red flags as in many cases, especially outside the United States the majority of women choose to terminate their pregnancy if the warning signs of Down syndrome are detected.

As our technology advances we'll be able to move from detection of these conditions to removal the first step down the road to so-called designer babies. The hope or concern is that soon enough we'll graduate from selecting out the bad genes to selecting in more favorable ones. This is where many people begin to cry eugenics and advocate extreme caution. Most people would probably agree that eliminating diseases like Huntington's or quality of life disabilities like poor eyesight would be a good thing and some even suspect that not editing out these genes would constitute an ethical failure in the future.

But what about giving your child a leg up on the competition by sprinkling in traits like increased height, or musical proficiency or above-average intelligence?

While the technology to do this is on its way, we're not there just yet. And it's expected to be very expensive at least. At first you might think well if you've got the money for it and it's legal. Why not you're just giving your child the best shot at a successful life?

Consider the following scenario:

A wealthy couple decide they want to enhance their baby's genes the average woman typically has 15 eggs extracted for an in-vitro fertilization procedure. Those 15 potential children will likely differ in IQ by about 20 to 30 points. The parents will be able to select the child or children with superior intelligence to carry to term.

Doesn't seem like that big of on the surface, but what happens when the top 10% of society can afford the procedure,

but the rest of the population can't? Now you have a society divided not only by the rapidly increasing wage gap,

but also by a new intelligence gap with wealthy children being far more likely to succeed than the 90 percent below them!

This would further stratify our world into the haves and have-nots with modified people only marrying and reproducing with other Modifieds. Thus keeping their gene pool more desirable the solution for this type of situation would be to make genetic modification accessible to all people. Giving everyone the ability to at least screen out disease and disabilities like poor eyesight.

But when we begin to dabble in aesthetic or additive modifications we get to the real dilemma of genetic engineering.

Just because we can do something doesn't necessarily mean we should do it! First comes the issue of deciding what this perfect human would look like if we learned anything from Germany during World War two it's that when one group dictates what features are best it can cause some serious problems! When parents can start designing their ideal babies like a piece of custom furniture there's a real danger that people will become competitive adding modifications in a never-ending quest to build the ultimate human child.

Then of course, there's the fact that our technology is rarely infallible. What happens when a couple orders a six foot four Greek god of a child and he only grows up to be six foot one?

Could they demand a refund? Would they feel cheated out of the product they ordered? How would their child feel about being considered inferior? And how would society treat him?

Then there's the international angle. China is already known for its questionable social engineering practices, such as limiting families to one child and taking children away from their parents to be enrolled in Olympic training schools, in an attempt to build future champions.

It doesn't take much imagination to assume that in a country like that, genetic modification would be seen as a very good thing.

Parents wouldn't have to worry about their one child being insufficient. They could order a smart strong handsome

male who would grow up to take care of his parents just like they'd always wanted. Olympic training schools would be packed with modified children suited to each event: Greater lung capacity and endurance for distance runners, a smaller leaner built for gymnasts, longer limbs for swimmers. When other countries use genetic modification to gain a competitive edge whether in sports or other more serious applications, what are the rest of us to do? It would be harmful to allow ourselves to be made non-competitive, but what would it cost to keep up? It would be expensive of course!

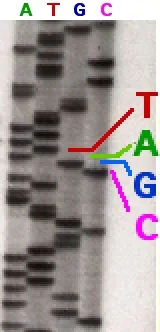

But extreme genetic engineering may also cost us some of our humanity and of course there's the potential for unforeseen health consequences to arise and modify children. DNA is incredibly complex and many traits aren't simply a one gene switch. What happens when we accidentally negate a gene that protects against the disease we have no experience with? Tinkering with systems we don't fully understand is a good way to end up in big trouble at the end of the day!

We have some important questions to consider when the technology is widely available will we have an ethical responsibility to modify our children to prevent disease or disability? Or is that just a part of being human? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.