The Purifying that paid off.

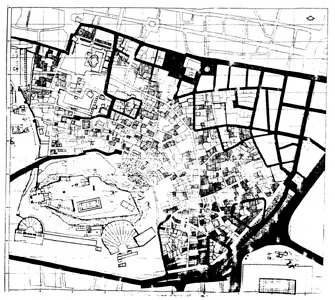

Map of the Plaka area

The final acceptance of the plan to save Plaka covered over 29,4 hectares, larger in area than proposal “D” as submitted by Professor Zivas and his team. The map shows the boundaries as proposed in this plan, extended even further to incorporate part of Monasteraki down to the railway. I spoke to Professor Zivas about the acceptance of Proposal D:

Q) Professor Zivas, this is a long process, tell me about the proposal finally accepted by the authorities for implementation.

A) Between the time of the proposals drawn in 1974 and 1975, and the rehabilitation project, there is a span of about four years. Intervention for the project began in 1979. The final decision was in the area to be detected and bigger than the plan chosen (Proposal D.¹) The final decision of all the area including Metropoleos Street, and even more, a small part of the Monasteraki square, (Flea Market) and the Roman Agora, Ermou Street and Railway, all were declared to be under protection.

The main measures approved and adopted by the government were firstly, a declaration of the boundary of the area, determined by streets such and such, all declared as a site under protection. Secondly, circulation and traffic control measures, pedestrianisation, etc., Thirdly, special code for descriptions for commercial signs, Fourth, declaration of buildings for special protection and the special buildings code for the Plaka eg: how one may build on an empty plot. Fifth and last, land use regulations, which functions may or may not be installed there and in other words not too many night club permits. For example the buildings do not have to be uniform in style since styles are so varied eg, the code is not so strict or rigid.

Q) When you say building codes were not so strict, would an ultra modern building be allowed?

A) Let us imagine we have a neo-classic house and a space in between, then another. Do we imitate? Or try to build modern buildings, respecting the style and atmosphere and rhythm and colour? The idea is not to be scenic or gentrified, the façade has to “fit in” with the remainder of the street. Buildings “under protection” were singled out as it would be impossible to change and take care of all buildings.

Q) So the codes are not that strict, it is a fascinating Subject.

A) It is fascinating and remains fascinating today because, unfortunately, it is the only example in Greece of such a detailed and extended study and implementation project. For me it’s hard to explain.

Q) It is still an on-going project, does your role remain the same?

A) From 1985 till today, there is a small group presided over by myself, four more persons, experts in public works, environmental specialists and so on, and this group has to follow the recommendations to see, consult and suggest etc.

Q) What would you say is the main problem?

A) The new commercial, touristic uses which are pressing to be allowed in – furs, jewellers, souvenir etc. This is a by-product of pedestrianisation.

Q) People will take advantage, of course, and although it’s still a “tourist trap” in a way, the tourists still love Plaka.

A) It is difficult to “do something about it”. It is provided in the land use regulations that the authorities can say one day: “OK I judge that the jewellers shops, for instance, are enough, and we won’t give any more licenses.” But you can understand how difficult it is to enforce, it’s hard to say “No”.

Q) It’s a continuous process, something you’ll probably never see the end of and certainly something that will not finish overnight. Will the small group go on convening for years, whether it changes its members or not?

A) The life of a town, or part of a town, cannot be followed by committee, life is so much stronger, life itself. With all this experience, the authorities should proceed with similar interventions in other parts of Athens historic neighbourhoods, not only in the small 40 hectares or so of Plaka, no matter how worthwhile. It is similar to Soho in London in size, (42 hectares) or Gamla Stan in Stockholm (35 hectares) or Nafplion with 40 hectares. It is useless to concentrate on one small area like Plaka only because it is evident that all the interests of the individuals, the shopkeepers etc, will be concentrated there, but if the authorities could extend all these efforts to the neighbouring districts, for example, Psirri or Metaxourgeion, or Thisseion and so on, I think that would be a good way of functioning.

Q) Are there buildings worth protecting in these areas?

A) A lot.

Since that interview in 1990, all three areas mentioned by Professor Zivas have been “regenerated”, some in part, some almost completely. Perhaps the example of Plaka made people more aware of what there is to save in a large city. It certainly was in the case of Athens.

Professor Zivas’ attitude was thast history is a living thing and in the case of Plaka, very much so. There are few areas in cities or capitals of the world which have successfully undertaken restoration of a particular quarter or section of a city and breathed new life into it. Stockholm’s Gamla Stan is one, Old Buda in Budapest is another, both fine examples of the sort of work Professor Zivas undertook.

From the first “serious pressures” from without appeared after 1950 and were mainly due to the building boom in Athens post war and the influx of population of the city. A second reason for pressure was the combination of the increasing needs of the commercial and administrative centre of the capital which touched on the boundaries of Plaka. Greece was at war and under German occupation until 1945 when its citizens underwent much hardship and starvation. Greece then had a bloody civil war until 1948.

The sharp increase in numbers of vehicles and therefore traffic was another minus to the health of Plaka, plus the encroaching tourist boom which increased the number of visitors to the district, one of the main attractions of the city and the quarter which offered pedestrians access to the Ancient Acropolis.

( )

)

The chapel of St George of the Rock.

The Plaka was, under these pressures, transformed in three ways. Functional transformation; the home, the artisan’s workshop, handicrafts and the traditional form of entertainment, trade in tourist gift shops and services. Theses factors were the cause of large numbers of the local residents to move out thereby resulting in the dissolution of the social structure of the district.

Town planning transformation; Plaka’s urban pattern was slowly being destroyed as the area was forced to accept the traffic caused by thousands of motor vehicles and to provide parking spaces for them. Noise, atmospheric pollution increased. The need for additional parking space caused the demolition of numerous houses, perhaps many of historic interest, gone forever. Some of the Plaka’s architecture wiped out for the tourist boom, in the days where people were unaware of what such a loss could mean.

The architectural transformation; the replacement of a considerable number of buildings during the two world wars, plus the changes in function of the Plaka district created this. Modest and sometimes poor quality of the buildings themselves plus poor maintenance and buildings put to uses incompatible with their original layout and scale.

Towards the end of 1974, the Ministry of Public Works, at that time responsible for area planning in Athens, decided to entrust a group of professionals under the direction of Professor Zivas, with the task of compiling a study of the overall problem. The group took two and half years to complete and form the first comprehensive analysing of the various problems besetting the district. The ultimate object of the study was to set out proposals for affective protection and preservation of the quarter.

The study group included a group of distinguished experts in varying fields², who applied basic principles which conformed with the most up-to-date and internationally acknowledged principles for conservation and protection. Together with the general conclusions reached in the study, these principles formed the foundation for the next stage.

After a period of stagnation between 1975-78, the Ministry of Housing, by then responsible for the area, entrusted a group of professionals, again under Professor Zivas, to study the measures necessary to protect and conserve the area. This new study aimed at proposing a specific strategy which would have two main targets. Firstly to ensure the broadest possible consensus for the measures and to minimize possible reaction to them, and secondly to provide possibilities for the adoption of general measures of immediate effect, whilst also making possible intervention by stages which, through a long-term programme could lead to the desired final result.

It should be pointed out that the group gave special consideration to the feeling of mistrust which had developed over two or more decades about the will of authorities to implement any programme or constant policy. The group sought to give minimum provocation to resistance to measures aimed at protection and preservation, plus “minimum disruption of life in such a central part of Athens,” Their first problem was to define the exact boundaries of the Plaka.

Adrianou street had long been a “boundary” created to protect archeological interests, in themselves important, but it became clear that acceptance of a broader area for Plaka as a uniform district constituted the first important step in the direction of its protection and conservation.

A second and important step was the “legal coverage of the existing pattern of the streets of Plaka which protects the district from any future alterations and preserves its urban form as it has been handed down to us.” It was deemed necessary to complement the fundamental functional change brought about to Plaka streets by pedestrianisation with a series of works which, on the one hand would emphasize this change, while on the other restore the street’s earlier appearance.

Every detail was taken into consideration. The services in the district were either very old or in some cases, non-existent. Renovation of water supply, drainage, electricity, town gas and telephones were recommended and by now, undertaken. The feasibility of a central underground T.V antenna cable to get rid of the awful TV antennas crowding the landscape, was looked into.

Athens the Parthenon

Natural stone slabs were recommended for use as paving, street lighting standards, replaces with exact replicas and the eventual removal of all overhead wiring to be completed. Basic legislation was drafted, and the basic precondition included that “Plaka should continue as a living quarter in the city’s life, and always remain.”

It is fortunate that the guardianship of such a delicate and essential area to the historic centre of Athens was under such a knowledgeable and dedicated individual as Professor Zivas. The result is what you see today if you decide to visit the marvellous place that is Plaka and the Acropolis in Athens.

¹ Proposal D

² First Study Group: Dr.J.Travlos, architect-archeologist, Dr (Mrs) J.Lambiti-Dimaki, Sociologist, Mrs A.Tzika-Hatziopoulou, Lawyer, Mr.P.Pamdikas, Economist, Mr.P.Pappas, Economist-statistician, architects J.Virakis, M.Grafakou and E.Maistrou, archeologists E.Spathari and A.Kokkou. Group led by Professor D.A.Zivas.

Second study group: Dr.J.Michael, architect and town planner, architects K.Ioannou-Gartzou, M.Grafakou, E.Maistrou, A.Paraskevopoulos and E.Methenitou. Civil engineer P.Keemezis and Mechanical engineer G.Kontoroupis. Traffic advisors, Professor G Yannopoulos and K.Zekos. Some of this group also took part in the first study.

The first part of this can be seen under history dated 06.09.17