In the early 18th century, when he was still resident at Cambridge University, Isaac Newton composed a new chronology of the world, one which broke radically with the Biblical timeline that had held sway in the West for more than a millennium. He later drafted a short treatise on the subject, which has remained largely unknown and unread to this day. The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended was published posthumously in 1728. This critique of Biblical chronology—at that time, the bedrock of Western history—is a startling anticipation of the Short Chronology, which I have been promoting on this blog for several years.

In the two preceding articles in this series, we looked at the first two chapters of this book, which dealt with the chronology of ancient Greek and ancient Egyptian civilization. In this article, we will look at the third chapter, in which Newton turns his attention to the chronology of the Assyrian Empire.

Chapter 3

This chapter of the The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended is entitled Of the Assyrian Empire. It is considerably shorter than the first chapter and less than half as long as the second. At the very outset, Newton repeats the now-familiar burden of his treatise:

As the Gods or ancient Deified Kings and Princes of Greece, Egypt, and Syria of Damascus, have been made much ancienter than the truth, so have those of Chaldaea and Assyria. (Newton 265)

As in the two preceding chapters, Newton is suspicious of the Classical accounts of Assyrian history to be found in the works of Diodorus Siculus, Ctesias, Herodotus, Ptolemy, and those who followed them. Instead, he takes his cue from Holy Scripture, the veracity of which he never questions, though his interpretation of it leads to a chronology that is quite different from the currently received one.

If, however, the Short Chronology is at all accurate, then Newton’s revision of Assyrian chronology may be in need itself of some revision, as we shall soon see.

Newton identifies the Biblical Pul (2 Kings 15:19) as the founder of the Assyrian Empire, rejecting any earlier Assyrian conquests as mythical:

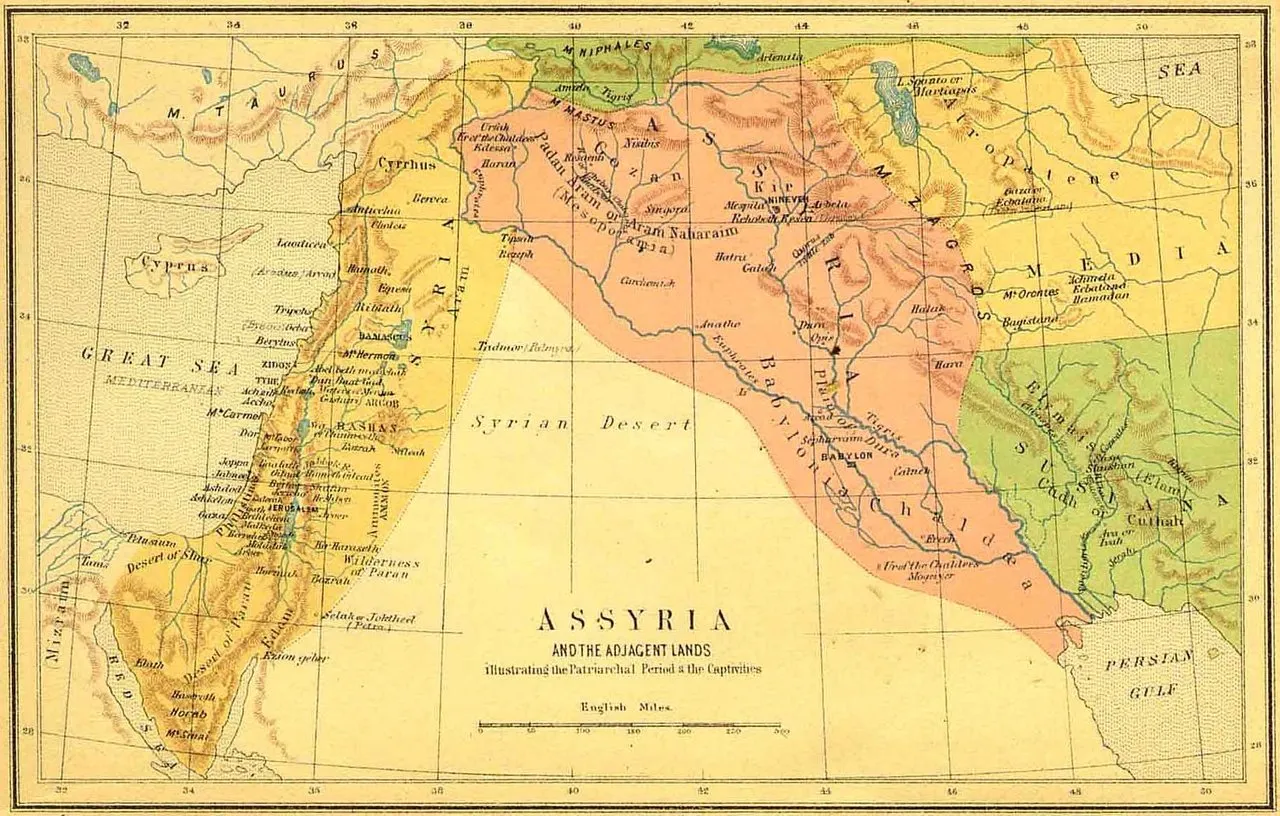

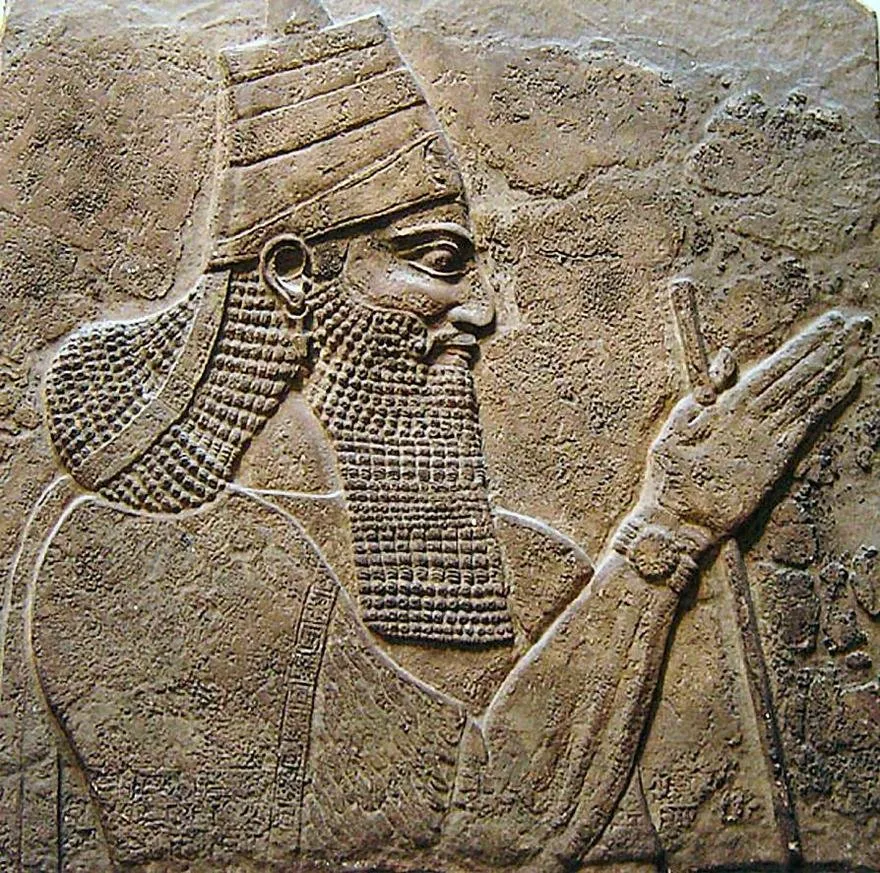

Pul, or Belus, seems to be the first who carried on his conquests beyond the province of Assyria: he conquered Calneh with its territories in the Reign of Jerboam, Amos i. 1. vi. 2. & Isa. x. 8, 9. and invaded Israel in the Reign of Menahem, 2 King. xv. 19. but stayed not in the land, being bought off by Menahem for a thousand talents of silver: in his Reign therefore the Kingdom of Assyria was advanced on this side Tigris: for he was a great warrior, and seems to have conquered Haran, and Carchemish, and Reseph, and Calneh, and Thelasar, and might found or enlarge the city of Babylon, and build the old palace. (Newton 277-278)

With the help of Classical sources—interpreted now in the light of the Biblical account—Newton proceeds to reconstruct the ruling dynasty of the Assyrian Empire. He equates the Bible’s Pul with Belus of the Classical sources:

Herodotus tells us, that one of the gates of Babylon was called the gate of Semiramis, and that she adorned the walls of the city, and the Temple of Belus, and that she was five Generations older than Nitocris the mother of Labynitus, or Nabonnedus, the last King of Babylon; and therefore she flourished four Generations, or about 134 years, before Nebuchadnezzar , and by consequence in the Reign of Tiglathpileser the successor of Pul: and the followers of Ctesias tell us, that she built Babylon, and was the widow of the son and successor of Belus, the founder of the Assyrian Empire; that is, the widow of one of the sons of Pul: but Berosus a Chaldaean blames the Greeks for ascribing the building of Babylon to Semiramis; and other authors ascribe the building of this city to Belus himself, that is to Pul. (Newton 278)

Today, Pul and Tiglath-Pileser [ie Tiglath-Pileser III] are generally regarded as one and the same figure, but in Newton’s reconstruction they were father and son. Newton also believes that Pul was succeeded in Babylon by a younger son Nabonassar. According to the conventional account, Nabonassar was not related to Tiglath-Pileser but was his vassal for the latter part of his reign. Inspired by a comment in Herodotus (p 229), Newton also suggests that the legendary figure of Semiramis was Nabonassar’s Queen. Today, Semiramis is generally identified with Sammu-ramat, an Assyrian regent who lived several generations before Tiglath-Pileser.

From all this it seems therefore that Pul founded the walls and the palaces of Babylon, and left the city with the province of Chaldaea to his younger son Nabonassar; and that Nabonassar finished what his father began, and erected the Temple of Jupiter Belus to his father: and that Semiramis lived in those days, and was the Queen of Nabonassar, because one of the gates of Babylon was called the gate of Semiramis, as Herodotus affirms: but whether she continued to Reign there after her husband’s death may be doubted. Pul therefore was succeeded at Nineveh by his elder son Tiglath-pileser, at the same time that he left Babylon to his younger son Nabonassar. Tiglath-pileser, the second King of Assyria, warred in Phoenicia, and captivated Galilee with the two Tribes and an half, in the days of Pekah King of Israel, and placed them in Halah, and Habor, and Hara, and at the river Gozan, places lying on the western borders of Media, between Assyria and the Caspian sea, 2 King. xv. 29, &: 1 Chron. v. 26. (Newton 280)

After Tiglath-Pileser there reigned in succession Shalmaneser [ie Shalmaneser V], Sennacherib, and Esarhaddon:

In the Reign of Sennacherib and Asserhadon [Esarhaddon], the Assyrian Empire seems arrived at its greatness, being united under one Monarch, and containing Assyria, Media, Apolloniatis, Susiana, Chaldaea, Mesopotamia, Cilicia, Syria, Phoenicia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and part of Arabia, and reaching eastward into Elymais, and Paraetacene, a province of the Medes. (Newton 283)

In the previous chapter, Newton identified Esarhaddon with Sargon II, whom Isaiah described parenthetically as the king of Assyria who sent Tartan to capture Ashdod (Isaiah 20:1):

And then Tartan was sent by Asserhadon with an army against Ashdod or Azoth, a town at that time subject to Judaea, 2 Chron. xxvi. 6. and took it, Isa. xx. 1. (Newton 256)

Cuneiform records indicate that Sargon II was actually the successor of Shalmaneser V and predecessor of Sennacherib. In the Short Chronology, he is equated with Darius the Great.

Newton also identifies Esarhaddon with Sardanapalus, who was the last Assyrian Emperor according to the Classical historian Ctesias—though not according to Newton:

Sardanapalus built Tarsus and Anchiale in one day, and therefore Reigned over Cilicia, before the revolt of the western nations: and if he be the same King with Asserhadon, he was succeeded by Saosduchinus in the year of Nabonassar 81. (Newton 285-286)

Saosduchinus refers to Shamash-shum-ukin, the eldest son of Esarhaddon and his successor as King of Babylon. Today, Sardanapalus is often identified with Ashurbanipal, another son of Esarhaddon, who succeeded him in Nineveh. In the Short Chronology, however, Sardanapalus is identified as Ashur-danin-pal, the Assyrian-born son of Shalmaneser III, who led a native rebellion against his father. Shalmaneser III is identified with Cyaxares II, the founder of the Median Empire (see below). Newton did not know of Ashurbanipal, who is not mentioned in the Bible or by any extant Classical source.

In the year of Nabonassar 101, Saosduchinus, after a Reign of twenty years, was succeeded at Babylon by Chyniladon, and I think at Nineveh also, for I take Chyniladon to be that Nabuchodonosor who is mentioned in the book of Judith; for the history of that King suits best with these times. (Newton 286)

Chyniladon refers to Kandalanu, a Babylonian king whose identity is still a matter of scholarly debate.

The fall of Assyria is now briefly recounted:

In the year of Nabonassar 123, Nabopolassar the commander of the forces of Chyniladon the King of Assyria in Chaldaea revolted from him, and became King of Babylon; and Chyniladon was either then, or soon after, succeeded at Nineveh by the last King of Assyria, called Sarac by Polyhistor: and at length Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabopolassar, married Amyite the daughter of Astyages and sister of Cyaxeres; and by this marriage the two families having contracted affinity, they conspired against the Assyrians; and Nabopolasser being now grown old, and Astyages being dead, their sons Nebuchadnezzar and Cyaxeres led the armies of the two nations against Nineveh, slew Sarac, destroyed the city, and shared the Kingdom of the Assyrians. (Newton 291)

Polyhistor’s Sarac probably refers to Sin-shar-ishkun, the son of Ashurbanipal who died when Nineveh was taken by a coalition of Medes, Chaldaeans, and their allies in 609 BCE (612 BCE according to modern historians).

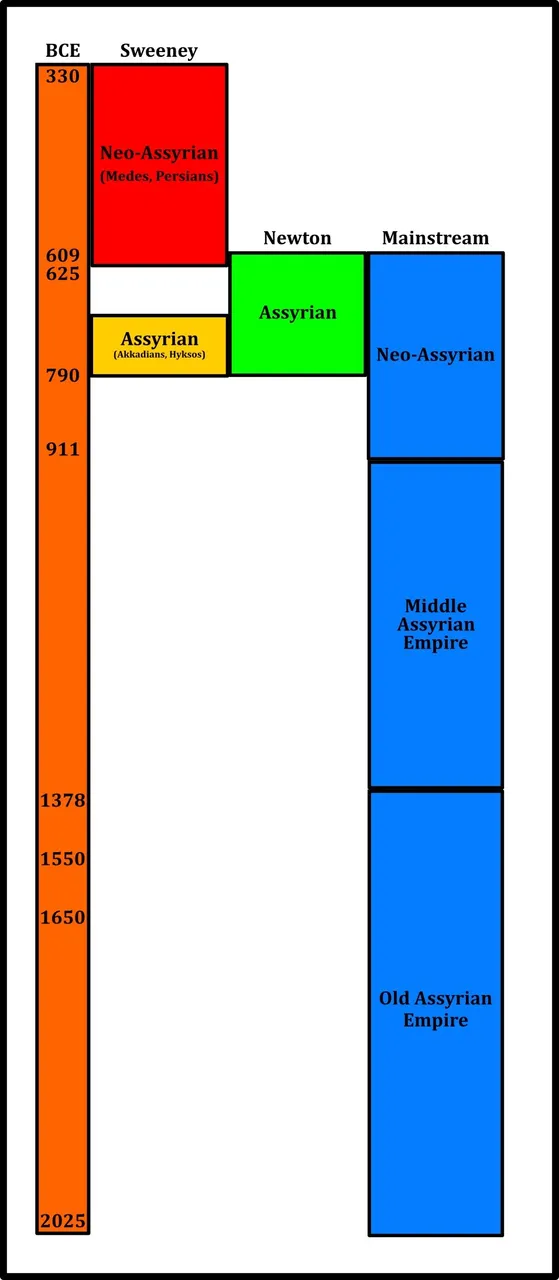

Newton places the Assyrian Empire between the years 790 and 609 BCE (Newton 34, 38). Modern historians call this the Neo-Assyrian Empire, to distinguish it from two earlier empires: the Old and Middle Assyrian Empires. But Newton and the Classical historians knew of only one Assyrian Empire, for there was only one.

Sweeney’s Model

In recent years, the Scottish historian Emmet Sweeney has been one of the most diligent promoters of the Short Chronology. In his Ages in Alignment series, he suggests that the fragmentation of the Kingdom of Solomon into two rival kingdoms—Israel and Judah—led to a confusion of Biblical chronology:

With the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel ... huge numbers of Hebrews were transported eastwards. These persons did not, as many suppose, immediately lose their identity. On the contrary, as the Scriptures themselves make perfectly clear, they continued as a distinct culture and people for many years—surviving indeed until the arrival in exile of their Judaic cousins over a century later. During these years, the exiled Ten Tribes interacted with their Persian conquerors, and some of the books of the Old Testament deal with the fortunes of these exiles under the various Persian Great Kings. However, even as the captive Israelites recorded their fortunes as exiles in Persia and Mesopotamia, the still free people of Judah also continued to keep records—records which told of their struggle for survival against the great power to the east which had already enslaved their Israelite cousins. The chroniclers of Judaic history however called this power and its kings by their Semitic names, whereas the chroniclers of the history of the exiled Israelites, living as they did in the Persian homeland, probably used the Persian names. Thus two parallel histories, one compiled by the free Jews, the other by the exiled Israelites, seem to have developed. When the Scriptures were being written in their final form, during the first century BC, the two distinct traditions were available. Clearly the use of totally different names for the same kings must have caused profound confusion, and eventually the parallel traditions were put in sequence rather than kept as they should have been, contemporary.

The misplacement of Persian history also therefore had the effect of throwing Hebrew history into chaos. (Sweeney 163)

According to Emmet Sweeney’s model of the Short Chronology, there was but one Assyrian Empire. This corresponds to what modern archaeologists call the Old Assyrian Empire, and it was identical to both the so-called Akkadian Empire and the Kingdom of the Hyksos. The Neo-Assyrian Empire of modern archaeologists is simply the Assyrian part of the empires founded by the Medes and the Persians, but misdated by about three centuries:

Not only was world history duplicated in the second millennium, as Velikovsky believed, but also triplicated in the third millennium. Yet this veritable comedy of errors had a rationale and followed its own internal logic. It was, as Heinsohn has demonstrated, constructed upon three quite separate dating blueprints. Thus the history of the first millennium, which is in fact the true history of the region, is known solely through the classical and Hellenistic sources and is dated according to these sources. A “history” of the second millennium, however, is supplied by cross-referencing with Egyptian material, and this chronology is based solely on these sources, which are dated via Eusebius/Manetho and the so-called Sothic Calendar. The final part of the triplication, the ghost-kingdoms of the third millennium, is supplied by cross-referencing with Mesopotamian cuneiform documents, and this chronology is based solely on these sources, which are ultimately dated on the basis of biblical history.

In this way the Imperial Assyrians of the 8th century BC, who are known from the classical writers, are identical to the Hyksos of the 16th century (who also supply the date for the Mitanni), who are known from the Egyptian sources, and are also identical to the Akkadians of the 24th century, who are known from the Mesopotamian sources. (Sweeney 75-76)

| Date | Neo-Assyrian | Neo-Babylonian | Mede | Persian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 625 | Shalmaneser III | - | Cyaxares II | - |

| 585 | Shamshi-Adad IV | - | Arbaces | - |

| 564 | Adad-Nirari III | - | Astyages | - |

| 559 | Tiglath-Pileser III | - | - | Cyrus II the Great |

| 530 | Shalmaneser V | - | - | Cambyses II |

| 522 | Sargon II | - | - | Darius I the Great |

| 486 | Sennacherib | - | - | Xerxes |

| 465 | Esarhaddon | - | - | Artaxerxes I |

| 423 | Ashurbanipal | - | - | Darius II |

| 404 | - | Nabopolassar | - | Artaxerxes II |

| 358 | - | Nebuchadrezzar | - | Artaxerxes III |

| 336 | - | Nabonidus | - | Darius III |

Neo-Assyrians, Neo-Babylonians, Medes and Persians (Sweeney)

Sweeney believes that the so-called Neo-Assyrian Emperors from Shalmaneser III on were actually the Assyrian names adopted by Median and Persian Emperors. Shalmaneser III was the Mede Cyaxares II. Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire, was Tiglath Pileser III—the Biblical Pul, whom Newton saw as the founder of the Assyrian Empire itself, in 790 BCE. Newton, however, distinguished Pul from Tiglath-Pileser, identifying the latter as the successor of the Pul in Nineveh, while Nabonassar was Pul’s successor in Babylon.

Following the Bible, then, Newton saw Pul as the founder of an empire—the Assyrian Empire. Following Sweeney, we see that Pul was indeed the founder of an empire—the Persian Empire.

To be continued ...

References

- Ctesias of Cnidus, John Gilmore (editor),The Fragments of the Persika of Ktesias, Macmillan and Co, London (1888)

- Leo Depuydt, More Valuable than All Gold: Ptolemy’s Royal Canon and Babylonian Chronology, in Piotr Michalowski (editor), Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Volume 47, American Schools of Oriental Research, (1995)

- Diodorus Siculus, Historical Library, Book 2, C H Oldfather (translator & editor), Diodorus of Sicily, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, LCL 279, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1933, 1989)

- Herodotus, A D Godley (editor & translator), Herodotus, Volume 1, The Histories, Books 1 and 2, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1975)

- Isaac Newton, The Original of Monarchies, Unpublished (1701)

- Isaac Newton, The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, J Tonson, J Osborn, T Longman, London (1728)

- Andrew Nichols, The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Florida (2008)

- Claudius Ptolemy, Handy Tables,

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

Images Credits

- Isaac Newton (1702): Geoffrey Kneller (artist), National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2881,Public Domain

- Assyria and the Adjacent Lands: Author Unknown, Public Domain

- The Assyrian Capital City of Assur: Véronique Dauge (photographer), © UNESCO, Creative Commons License

- Tiglath-Pileser III: British Museum BM 118900, Public Domain

- Artist’s Impression of Ashurbanipal’s Palace in Nineveh: James Fergusson (artist), Austen Henry Layard, The Monuments Of Nineveh, London (1849)

- Emmet J Sweeney: © Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (SIS), Fair Use