The Short Chronology is a radical model of ancient history developed by a number of independent researchers in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The name was popularized by one of these researchers, Lynn E Rose (1934-2013), Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University at Buffalo. Prominent also among the creators of the Short Chronology were Gunnar Heinsohn, Charles Ginenthal (1934-2017) and Emmett Sweeney. Important contributions were also made by Lewis M Greenberg, Ralph E Juergens, Clark Whelton, Irving Wolfe, Birgit Liesching and Frank Wallace.

The Short Chronology, which involves a drastic shortening of the timeline of ancient history, is a work in progress. In some areas, there is still considerable disagreement among its adherents. In other areas, there are unresolved difficulties. The creators of this model entered this field from mostly unrelated disciplines. Gunnar Heinsohn is an economist. Lynn E Rose taught philosophy. Emmett Sweeney studied early modern history. They all have one thing in common, though: to one extent or another, they are all Velikovskians. That is to say, they can be regarded as disciples of the maverick Russian scholar Immanuel Velikovsky.

Velikovsky made two significant contributions to the field of ancient history:

He revived and reinvigorated the theory of catastrophism.

He drastically revised the chronology of the ancient world.

Velikovsky may be justly called the Father of the Short Chronology. His revised model of ancient chronology provided his disciples with a point of departure—a groundwork on which to build. But they went well beyond the limits to which Velikovsky himself was prepared to go. The model that Lynn E Rose dubbed the Short Chronology involves revisions to the traditional timeline of ancient history far more radical than any envisaged by Velikovsky. Although the adherents of the Short Chronology may consider themselves Velikovskians, I suspect that Velikovsky himself would be quick to denounce them for betraying his vision.

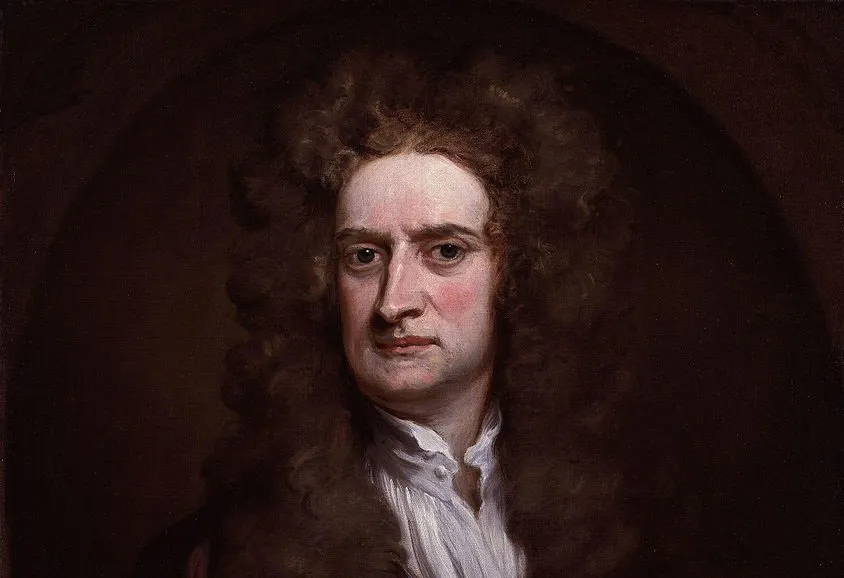

Although the Short Chronology is a relatively new hypothesis, its proponents were not the first scholars to suggest that ancient history began much more recently than is generally believed. It came as a considerable surprise to me to discover that while Velikovsky was undoubtedly the Father of the Short Chronology, no less a figure than Isaac Newton could be regarded as its Grandfather.

In the early 18th century, when he was still resident at Cambridge University, Newton composed a new chronology of the world, one which broke radically with the Biblical timeline that had held sway in the West for more than a millennium. He later drafted a short treatise on the subject that has remained largely unknown and unread to this day. The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended was published posthumously in 1728. This critique of Biblical chronology—at that time, the bedrock of Western history—is a startling anticipation of the Short Chronology.

It is easy to stop one’s ears when a psychiatrist, an economist or a professor of philosophy dares to preach on the subjects of ancient history and archaeology. But when a man of genius like Newton speaks, it were wise to listen.

The Bible

The traditional chronological framework sits on a foundation of Biblical scholarship. Modern historiography dates from the Age of Enlightenment, and most of its leading lights were secular scholars. Several were even unashamed atheists. But by the time these rationalists and freethinkers began their studies, the general framework of ancient history and its chronology had already been established by the religious scholars who had preceded them. These religious scholars—Christian clergymen for the most part—drew their inspiration from both the Bible and the historians of the Classical world. Long before modern methods of historiographical research had been developed, and centuries before the scientific discipline of archaeology had been introduced, the broad brushstrokes of ancient history were already in place.

In 1583, the French polymath Joseph Scaliger published his Opus de Emendatione Temporum, in which he “corrected” the chronology of the World. Scaliger revolutionized the science of chronology. He was one of the first scholars to apply modern methods of critical analysis to historical documents. He also used astronomical records to establish a number of significant dates and to align disparate chronologies. Nevertheless, he still accepted that the Creation of the World as described in Genesis was a historical event, placing it in the year 3949 BCE.

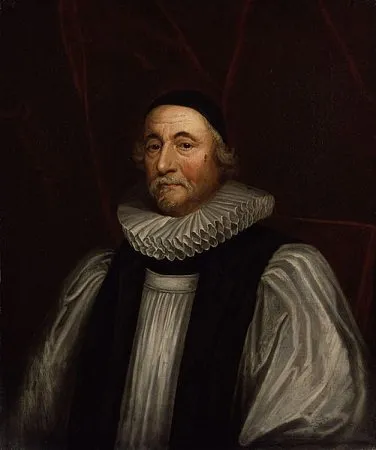

It was a compatriot of mine, James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland, who consolidated the foundations of our modern chronology. In Ireland there was already a well-established custom of compiling annals. How much the poorer our literary heritage would be without the Annals of the Four Masters, the Annals of Ulster, the Annals of Inisfallen, the Annals of Tigernach, the Annals of Connacht, the Annals of Loch Cé, and a dozen other sets of annals I could name. But Archbishop Ussher was not satisfied with treading in the footsteps of his Popish predecessors. He set himself the much more daunting challenge of compiling the annals of the whole world.

Drawing upon a wealth of written traditions—the Bible, Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius, Diodorus Siculus, Quintus Curtius Rufus, Arrian, and dozens of minor scholars—he spent perhaps ten years of his life compiling the monumental Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti, a prima mundi origine deducti, una cum rerum Asiaticarum et Aegyptiacarum chronico, a temporis historici principio usque ad Maccabaicorum initia producto. (Annals of the Old Testament, Deduced from the First Origins of the World to the Beginning of the Maccabees, Together with a Chronicle of Asiatic and Egyptian Matters), which was published in 1650. A continuation, Annalium pars posterior (The Latter Part of the Annals), appeared in 1654 and brought the annals down to AD 73. The first English translation of the complete work was published in 1658. Recently, this translation was updated for the modern world by Larry and Marion Pierce as The Annals of the World.

It was in this mighty tome that Ussher famously dated the Creation of the World to 4004 BC. Ussher’s chronology built on the pioneering efforts of his predecessors—most notably Scaliger and John Lightfoot—and cemented the Biblical timeframe in place. Since then, almost every mainstream scholar who has studied the history of the ancient world unquestioningly accepts Ussher’s timescale, more or less: civilization arose in the Near East in the fourth millennium BC, and the succession of kingdoms and empires followed the scheme laid down in his Annals of the World.

The fact is that despite the Enlightenment, the Age of Reason and the Scientific Revolution, the chronology of ancient history that is taught in universities across the globe today is barely indistinguishable from that published by Ussher in 1650. The majority of today’s historians and archaeologists may not be Creationists—they do not believe that the World was created in six days in 4004 BC—but they still place the rise of our civilization in the Near East about five thousand years ago.

The Original of Monarchies

Isaac Newton was a man out of his time in more ways than one. While he is best remembered for his pioneering investigations in the fields of mathematics and natural philosophy (ie science), he also carried out researches into alchemy, Biblical exegesis, prophecy and chronology. He was an independent thinker in the realms of religion and theology. His views on the Trinity were considered so unorthodox that a special dispensation from Charles II was required before he could be elected a Fellow of Trinity.

Newton’s interests in history and chronology were probably sparked by his Biblical studies, which can be traced back to the 1670s. At the beginning of the 18th century, he drafted a short treatise entitled The Original of Monarchies, which described the rise of several dynasties in antiquity and traced their lineages back to Noah. This was Newton’s first venture into the field of chronology.

In the first half of this work, Newton restricts himself to relative rather than absolute chronology. For example:

For the whole Assyrian Monarchy seems to have risen out of such little kingdoms as these not long before the captivity of the ten tribes. The Prophet Amos about sixty or seventy years before that captivity, thus threatens them with what had lately befallen other kingdom ... Tis true that this City [Nineveh] including the large gardens & suburbs for feeding of Cattel, was a great city in the days of Ionah that is about eighty or an hundred years before the captivity of the ten tribes. Nahum who lived after the reign of Sennacherib represents that it had been long a populous city, and Herodotus that it reigned over the upper or greater Asia 500 years. And so long perhaps it might have been one of the greatest cities in the east, but yet it grew not up before the reign of Pul to that extent of Dominion which was called the kingdom of Assyria & accounted one of the great monarchies ... Cecrops the first king of Attica was only a Captain of the forces of all the cities elected in time of danger. According to the Arundelian Marble he was made their captain or king about 63 years before Cadmus brought letters into Europe, & Theseus was contemporary to the Argonauts, being the predecessor of Menestheus who went to the war of Troy ... They [the Latins] had a king before the Trojan war but without being united under him. For about 32 years after that war Ascanius the son of Æneas built the city Alba ... etc.

But about halfway through the treatise, Newton writes:

For better understanding the ancient state of Greece & Italy, the Chronology of those times is to be rectified. ffor the Europeans had no Chronology ancienter then the Persian Monarchy. And whatever Chronology we have now of ancienter times has been framed since by reasoning & conjecture.

In that sentence lie the seeds from which his later work grew. He next warns the reader of the uncertainty of dates earlier than the Persian Empire:

Pherecides Atheniensis in the reign of Darius Hystaspis or soon after wrote a large book of the Antiquities & ancient Genealogies of the Athenians & was one of the first European writers of this kind, whence he had the name of Genealogus And by these Genealogies the Greeks estimated times past but computed not by any Æra till about the end of the Persian Monarchy. Hippias who lived in the end of that Monarchy was the first that counted by the Olympiads & was derided for it by Plato. Plutarch [Numa] saith that Hippias published a Breviary of the Olympiads supported by no certain arguments The Arundelian Marbles were composed 60 years after the death of Alexander the great & yet mention not the Olympiads, so that this Æra was not then received tho it be now reputed the principal Æra of the Greeks. The annual Archons of the Athenians may be relied on as high as the warr of Darius Hystaspis with the Greeks, but in ancienter times are set too early with great intervalls of time between them. Plutarch [Romulus, Numa] represents great uncertainty in the originals of Rome & so doth Servius [Aeneid 7:678]. The old Records of the Latins were burnt by the Gauls 64 years before the death of Alexander the great & Q. Fabius Pictor the oldest historian of the Latins lived 100 years later then that king.

It is now that Newton first suggests that the history of the world may not be as ancient as we are led to believe:

Now all nations before they began to keep exact accompts of time have been prone to raise their antiquities & make the lives of their first fathers longer then they really were. And this humour has been promoted by the ancient contention between several nations about their antiquity. For this made the Egyptians & Chaldeans raise their antiquities higher then the truth by many thousands of years. And the seventy have added to the ages of the Patriarchs. And Ctesias has made the Assyrian Monarchy above 1400 years older then the truth. The Greeks & Latins are more modest in their own originals but yet have exceeded the truth. ffor in stating the times by the reigns of those their kings which were ancienter then the Persian Monarchy they have put those reigns equipollent to generations & accordingly made them one with another about an age a piece recconing three ages to an hundred years. For they make the seven kings of Rome who preceded the Consuls to have reigned 244 years which is one with another 35 years a piece & the 14 Kings of the Latines between Æneas & Numitor or the founding of Rome to have reigned 425 years which is above 30 years a piece, & the first ten kings of Macedon (Caranus &c) to have reigned 353 years which is above 35 years a piece & the first ten kings of Athens (Cecrops &c) 351 years which is 35 years a piece, & the eight first kings of Argos (Inachus, Phoroneus &c) to have reigned 371 years which is above 46 years a piece:

Whereas according to the ordinary course of nature kings reign one with another but about 20 years a piece. So the 18 Kings of Iudah who succeeded Solomon reigned 390 years which is one with another 22 years a piece. The 15 Kings of Israel after Solomon reigned 259 years which is 17¼ years a piece. The 18 Kings of Babylon (Nabonasser &c) reigned 209 years which is 11⅔ years a piece. The 10 Kings of Persia (Cyrus &c) reigned 208 years which is almost 21 years a piece. The 16 successors of Alexander in Syria (Seleucus &c) reigned 244 years which is 15 years a piece. The 10 in Macedonia (Aridæus &c) 156 years which is 15½ a piece. The 28 Kings of England (William the Conqueror & his successors) 635½ years which is 22⅔ years a piece. The sixty & three kings of France (Pharamund & his successors) 1224 years which is 19½ years a piece. Generations from father to son may be recconed one with another about 33 or 34 years a piece or three generations to an hundred years. But if the Generations proceed by the eldest sons they are shorter so that three of them may be recconed to eighty years. And the reign of Kings is still shorter because Kings are succeeded not only by their eldest sons but sometimes by their brothers and sometimes they are slain or deposed & succeeded by others of an equal or greater age, especially in elective & turbulent kingdoms.

Using this yardstick, Newton adds up the successive reigns of kings according to various lists in order to estimate the time of the Trojan War—but only in relation to the reign of King Solomon:

Whence the taking of Troy will be about 70 or 80 years later then the death of Solomon ... At which rate the destruction of Troy will be about 90 or 95 years later then the death of Solomon ... at which rate the destruction of Troy will be about 90 years after the death of that king ... & the destruction of Troy which was one generation later was about 88 years after the death of Solomon ... Whence it follows that Troy was taken about 70 or 80 years after Solomon’s death ... which together with the four last years of that war being counted from about the tenth or twentieth year of Davids reign will place the taking of Troy about 80 years later then the death of Solomon as above.

Newton never completed this brief treatise. It breaks off with the words:

One of the first great kingdoms in the world was that of Egypt. For Pliny in recconing up the first inventors of things ascribes to the Egyptians the invention of a royal City & to the inhabitants of Attica that of a popular one. Which is as much as to say that Athens was by the Greeks accounted the first city in the world under which other cities united into a popular dominion by a Common Council & the Egyptian Thebes the first City which became the seat of a Monarchy. For Thebes was famous in Homers days when the four Monarchies & their head cities were not yet talked of. For, saith Strabo, Homer knew nothing of the Empires of the Medes & Assyrians, otherwise naming the Egyptian Thebes & her riches & those of the Phenicians, he would not have passed over in silence the riches of Babylon, Nineveh & Ecbatane. And for the same reason Memphis also & its miracles grew up after Homers days. We have shewn how the cities of Egypt united very early into small kingdoms, & how those kingdoms grew at length into one Monarchy seated first at Thebes & then at Memphys remains now to be explained.

Most of this short treatise was later incorporated into Newton’s later work, The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, which he probably began to write shortly after abandoning The Original of Monarchies. And it is to that later work that we must now turn our attention.

To be continued ...

References

- Isaac Newton, The Original of Monarchies, Unpublished (1701)

- Isaac Newton, The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, J Tonson, J Osborn, T Longman, London (1728)

Image Credits

- Isaac Newton (1702): Geoffrey Kneller (artist), National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2881,Public Domain

- Immanuel Velikovsky: Wikimedia Commons, Donna Foster Roizen (photographer), © Frederic Jueneman, Creative Commons License

- James Ussher: Wikimedia Commons, National Portrait Gallery, London, Peter Lely (painter), Public Domain

- The Annals of the World: © Larry and Marion Pierce, Fair Use

- Trinity College, Cambridge (1690): David Loggan (engraver), Cantabrigia Illustrata, Cambridge (1690), Plate XXIX (cropped), Public Domain