abject stench strange uncanny perspectives

from underneath the foot of an ant

the same but in a different light

inside out and outside in

the normality of the everyday a fictive myth

just to stay sane in a crazy world

face to face with the abject other

that challenges the walled-in borders

of a mythical detached reality

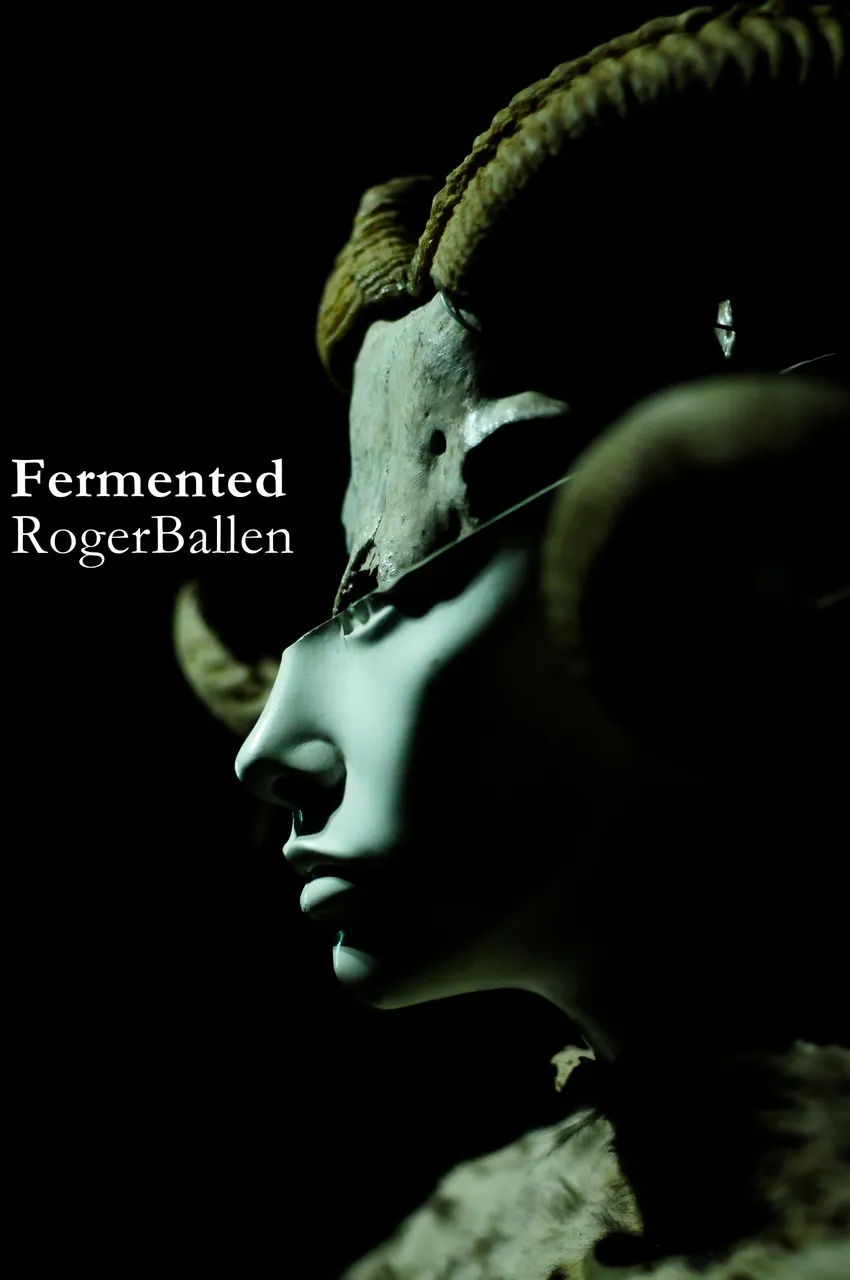

The second part confronting the uncanny and abject of what is Roger Ballen culminates in yet another strange and uncanny post. The photographs illustrate yet again the weird and unsettling art of Roger Ballen. As was the case with the previous post and this one, these images are unsettling and might deal with topics some might find upsetting. Yet this is where the power of Ballen’s art resides: in the questioning of our own reality with the confrontation of the strange and uncanny, we might come to a better understanding of ourselves. Or we might merely become more aware of the borders we construct around reality. This is also the topic that the essay (at the bottom of the post) deals with.

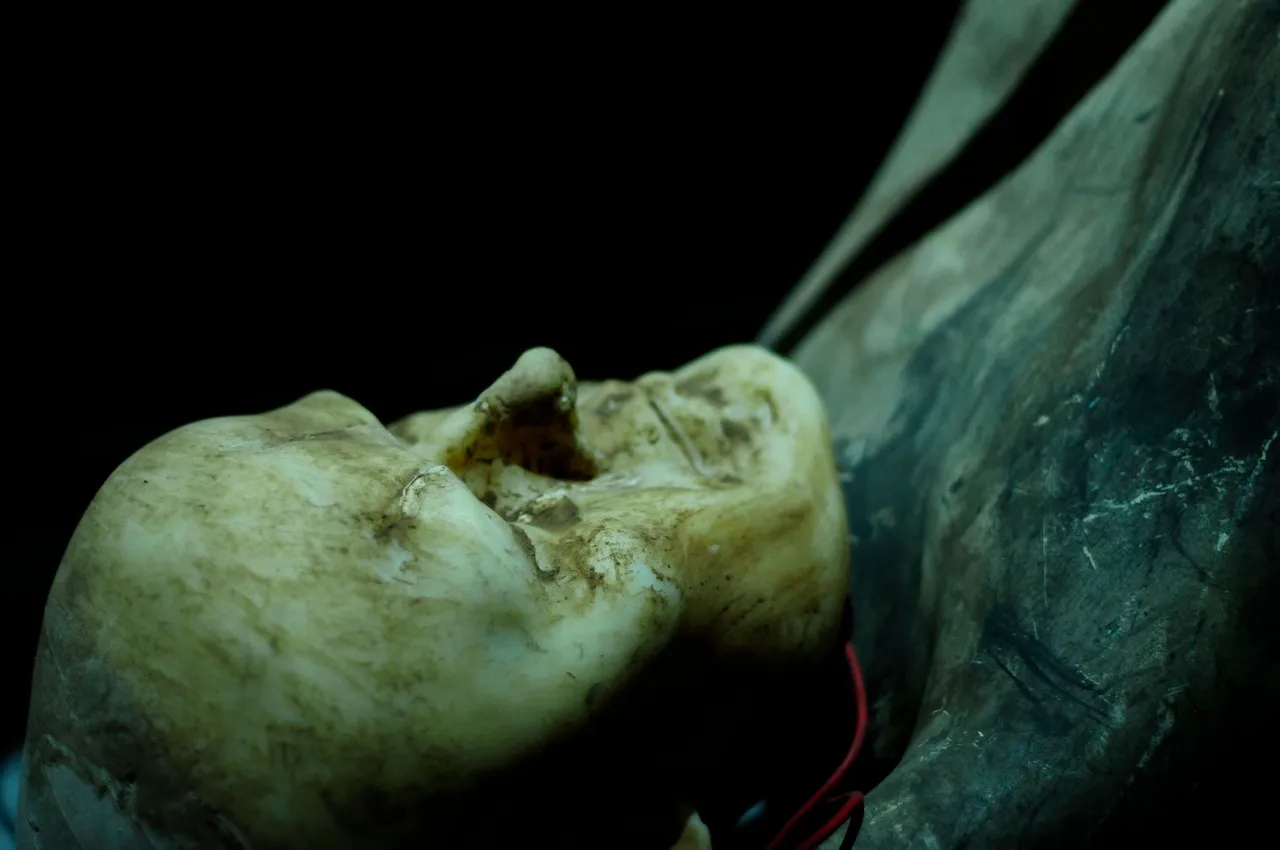

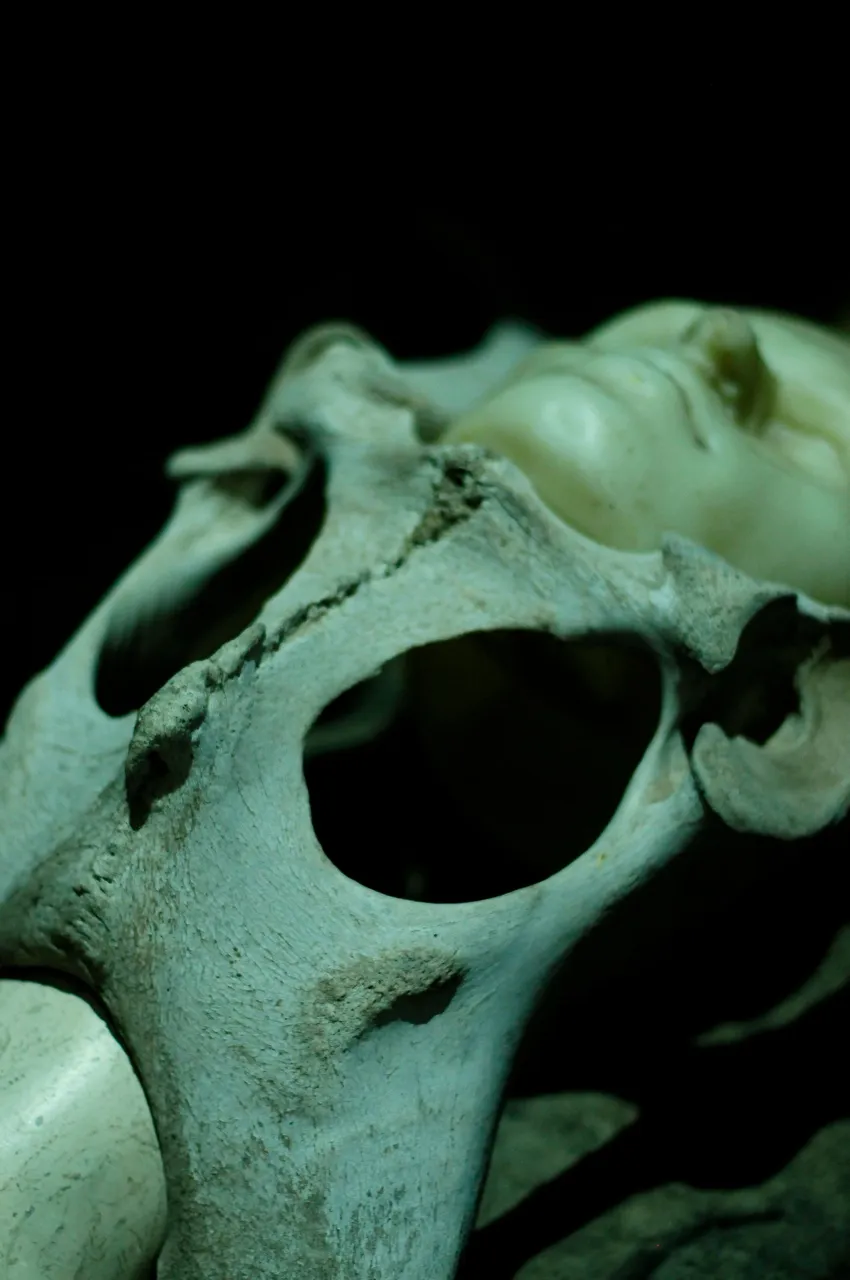

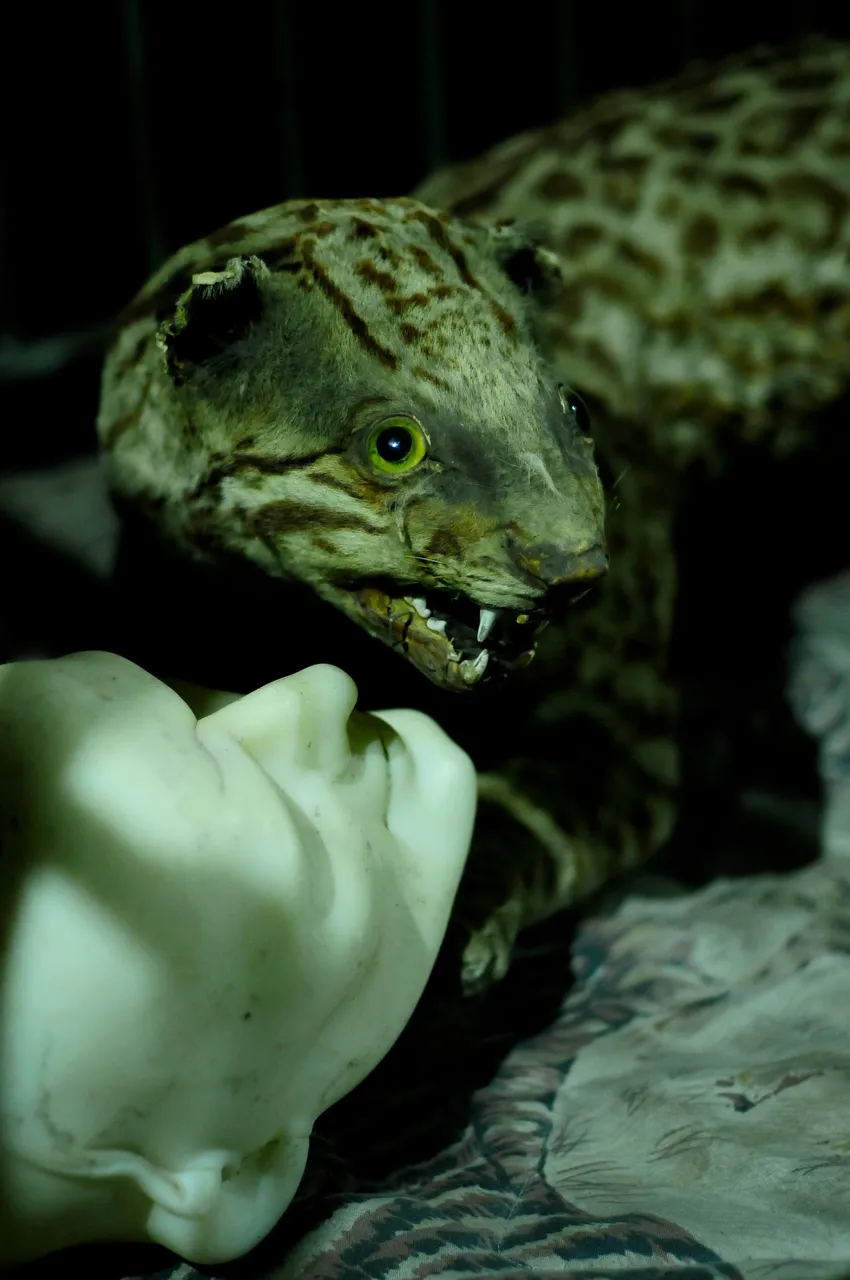

These photographs home in on the strange and the abject. Some of the lighting in this post was very good, adding to the strangeness of the overall experience, highlighting (I think) the uncanny and liminality. Liminality in the sense that these objects and art pieces reside in the “in-between spaces” of our reality. They are situated (read: locked away) in an art gallery, they are thus not part of the quote-unquote “real world”. They exist in a place removed from reality, yet not outside of reality as such. An art gallery becomes a kind of liminal space, a purgatory of artistic ideas that can never escape either the artist’s mind or the gallery itself. Ballen’s art is similar to this liminality. We see, in a safe space, the abject, the true horror, that tries to disrupt our everyday lives, but we can escape it with ease to “return to everyday life”, so to speak. We leave Ballen behind as soon as we get out of the art gallery that exists as a type of liminal space.

Before I carry on (in the essay at the bottom of this post), let me first provide you with the photographs of the strange, of the uncanny, of the abject.

(Note/Warning: The following images show content that some might find unsettling and disturbing. Please proceed with caution if you are a sensitive viewer. The essay below also deals with topics that might be unsettling and disturbing.)

Confronting the Abject

|  |

|---|

|  |

|---|

Reading Roger Ballen’s Art as Abject - A Philosophy Essay

We are drenched in familiarity. We wake up in the same bed, with the same routine, almost every day. Our lives are bordered, systematised, walled in, we are drenched in familiarity. There is nothing strange that confronts us. When something breaks down, when an object becomes “present-at-hand” opposed to “ready-at-hand” (in Heideggerian terms), when an object becomes something we contemplate in a broken state opposed to using it in a non-contemplative state, the familiar object becomes strange, unfamiliar, abject, horror. It ceases to blend into the background and stands out in a confrontational state; it presents itself to us for contemplation. The coffee machine that breaks down and therefore ceases to be familiar, becomes something of a horror, a strange object. For when it worked, we rarely contemplated it, we only began contemplating the machine as soon as it broke down, as it ceased being part of the background. As soon as it became strange, abject, going beyond familiarity, it challenges that very familiarity that structured our world.

The idea that the abject disrupts and disturbs the familiarity and structure of our world originates somewhat with the philosopher Julia Kristeva from the psychoanalytic tradition. In her work, the abject, horror, strange, does not “respect” the rules of the familiar, the structured world. The abject then becomes something that challenges the safe and familiar structure of our world, the walls we build to keep the strange out, the way we make sense of our world through rigid constructs. The abject is the strange that does not fit in these rigid boxes we made to comprehend the world. But because it does not fit, and because we stand in a contemplative relationship with it, rather than a utilitarian or pragmatic relationship, it challenges these very boxes, borders, walls, categories, we draw to stand in a familiar relationship with the world. Because we are viewing the object in a conscious and reflective state, it coincidentally causes us to contemplate them. It challenges us to think about the walls we erected, the borders we drew, the boxes we construct to make sense of the world.

When the coffee machine – which functions in a pragmatic or utilitarian way in the familiar background – breaks down, it challenges us to contemplate the borders of familiarity. This example is obviously a very tame one. The broken coffee machine as abject does not challenge the borders of our world too much, or to such an extent that it disrupts the borders. It brings us close to the borders, making us aware of them, challenges us to see the once familiar object now as unfamiliar.

Only when we are confronted with the “other” as abject, does the confrontation begin to challenge us in a way that disrupts our comfort in our world. The “other” functions as a fictive reality of that which we detest, which we want to get rid of. The “other” is the parts in our world that we cannot stand to confront, that which disgusts us and which our moral code denounces. The “other” is never something outside of us, it is never an “other” being. The “other” is always a fiction, a myth, something our subjectivity creates. We then impose this view onto “another” that perfectly matches the fictive, the myth, the creation. Colonialism is always used to explain this function of “othering”. The colonialists detested from a moral perspective a-morality. Everything that the colonialist detested was the “other”, sinful, horror. The “other” confronted the colonialist in living form as they sailed to far away lands. The African, the Indian, the Chinese, became the “other”, the personified a-morality that the colonialist yearned for. The African, the Oriental, as the “other” never was a-moral, rather, they became a-moral in the moral framework of the European Christian. The “other” was thus constructed, the African, the Indian, the Oriental became the other, the fictive myth of a-morality, what the European or the Occident detested. The European Christian created a framework in which the “other” came to life.

The “other” in this fictive myth became the abject, the very thing that challenged the familiarity of the secure way of life. The rigid borders of morality crumbled in the face of this abject other. In the colonial myth about Africans, Indians, the Occident, the colonist and the Christian European saw the face of a-morality, original sin, strangeness, horror. The rituals of Africans, similar to those of Christian Europeans (even though they will never admit this) became the face of damnation, of everything sinful, detestable, vile, dirty, taboo. The abject other does not exist, it is merely a creation from one’s own subjective experience of what one’s rigid borders keeps out, that is, the other. This is imposed onto things and people that then become “other” from our own lifeworld. My “other” constitutes the things that I find detestable from my moral framework. As I impose this “other” that I created on others, they become the “abject other”, that which threatens to destroy the rigid borders I constructed to make sense of the world. Through my own constructions, I cause the very world that had structure to collapse.

What does this have to do with Roger Ballen’s art? For me, his work symbolizes and concretises the Abject Other. His creations illustrate the very detestations, the taboos, the “otherness” we relegate to the periphery or the border. Through his art, we confront what lays outside of the borders we constructed, what our walls keep out, what our rigid structures keep at bay. His art confronts this, the abject, the other, the taboo, the strange, that which we want to keep out, that which threatens our sanctity in the secure and familiar. The objects he presents contains elements of familiarity, that which we can make sense of, but his art blends it with things that scare us, that detest us, that causes a stirring in our moral being. The use of death alongside life, the religious imagery juxtaposed against a-morality, the confrontation with the living conditions of people we relegate to the periphery. All of this challenges our borders, challenges the safety we gained from living a life without contemplating things. In Heideggerian terms, the artworks of Ballen presents us with things, objects, beings that are “present-at-hand” opposed to “ready-at-hand”. They do not blend into the familiar background with things “working”. Instead, they are “ready-at-hand”, challenging us to confront it in a contemplative state, they are the abject, the other, that we tried to wall out, border away, shift to the periphery, where we do not have to think about them.

Ballen’s art confronts us with our own morality. What is it that our morality asks us to shun? What is it that our familiarity with the world relegates to the periphery or the border or the wall that we never peek over? What lies on the other side of the other? Ballen’s art asks us to question the things that we always confronted in a non-contemplative stance. We come face to face with our demons, so to speak. The things we constructed from the confrontation with that which challenges our sanctity of familiarity, that which challenges us and which we wanted to keep out, confronts us in living form. Or life-like rather than living.

In the liminal space of the gallery, we confront the other without the fear of losing everything. Unlike the colonial experience, or the experience of the colonised of the coloniser, we do not experience a life-threatening situation. But unlike the routine and commonplace example of the coffee machine breaking, which does not challenge us in the same way, the confrontation with art that challenges our rigid borders can be life-altering. From the confrontation with the abject other in art form, we can realise that our rigid border is not so rigid, and we can realise that our world is not so secure in terms of morality. We can gain an extreme nuance that alters our being-with-others in the sense that we do not impose our moral framework on others, thereby imposing our own “otherness” on the other, creating the fictive and abject “other” that we detest. We might understand that this process is shortsighted, myopic, outmoded, outdated, and completely fictive/mythical. The other in us, relegated and imposed onto the abject “other” is what creates distance, racism, hatred, discrimination. The abject “other” is what causes sexism, moral disputes without answers, extremism. Because in the end, all abject “othering” is based on the fictive and mythical that we fear.

Confronting Roger Ballen’s art reminds us that that which scares us, that which threatens our secure sense of being in the world, is all based on the subjective constructions of what we detest in our own being. The other is rarely really the other, it is more often than not creations/myths we constructed to make sense of the world, and thereby creating the abject “other” that challenges to ruin our stability.

Postscriptum, or In the Abject we Believe | PLUS an update on the Laptop Situation

Horror movies always threaten our sense of security. The monster under our bed, the burglar wanting to get into our secure home, the alien creature threating either the world or our sense of being alone in the universe, horror always reside in and rely on our sense of the world that functions according to our structures. Horror, simply put, illustrates what happens when the world as we constructed it ceases to function as we want it to function. There is always something external to us that threatens familiarity. But this is never really something outside of us that scares us. Even though horror portrays that the alien is something external, it is always something internal. The “alien” is almost always the “other” of humanness, that which we contrast ourselves with the create the myth of our own superiority but also familiarity. The alien is our confrontation with what we perceive as unfamiliar. The alien is never something in and of itself that comes from outside our universe, it is almost always something internal to use, that which we push to the side, the periphery, as opposed to ourselves or the familiar.

The alien, in its confrontation as horror, is always a subjective externalisation of our internal fears…

In any case, I hope that these photographs caused some fear in you, or some disturbance. I loved our visit to the Inside out Centre for Arts as it again challenged my own conception of, amongst other things, art and what I find horrific, detestable, and so on. I hope that my photographs of Ballen’s art could inspire the same in you.

For now, happy photographing (and thinking about confronting our inner abject “other”) and stay safe.

All of the musings and writings are my own, unless I stated otherwise. The photographs are also my own, taken with my Nikon D300 and Nikkor 50mm lens. I got permission from the artist himself to photograph his artworks.

PS. I am writing on my laptop, which if you read my post yesterday, I had an unforeseen accident where some water managed to get onto my laptop. I think my laptop survived it, as I was maybe a little too cautious. But rather safe than sorry.