At about last year at this time, my devoted interest in the singing of the great basso profundo Kurt Möll caused YouTube to serve me Brahms's Vier Ernste Gesänge – Four Serious Songs.

Although I did not remember at the time, November 2021 marked almost sixteen years since discovering Bach's B minor Mass gave me the emotional outlet I needed to cope with my grandmother's death … music has a way of finding me when I need it the most.

Brahms's Four Serious Songs arose from his grief because of the stroke suffered by Clara Schumann, a close friend and mentor – the knowledge of her imminent death drove him to find inspiration in some of the gloomiest texts of the entire Bible. This would be his own last song cycle, for while Frau Schumann was passing away in the spring of 1896, Brahms himself knew his time was near – and indeed, the spring of 1897 marked his own death. Already, both had mourned the loss of Robert Schumann, who had passed away entire decades earlier, and some of the Schumann children.

That such music, and musicians, and friends, and mentors, and loved ones, should DIE – should DIE, leaving all things behind, after all their vitality and joy had been sapped by age and illness or both – DIE, just like those not so beloved and gifted, die like the wicked also – that no one should be spared this agony – this troubled old King Solomon, who wrote the book of Ecclesiastes in Scripture and observed that, “under the sun,” all mankind suffered the same fate, no matter how wise or foolish.

That no one might be spared, no matter how precious – the reality has grieved the heart and tested the faith of mankind, and in the first of the serious songs one can hear both Solomon and Brahms wrestling with the idea – “Denn es gehet dem Menschen wie dem Vieh,” which is translated at least on Wikipedia as “It is for the person as it is for the animal.” Me with my little German skills reads that as “Then goes mankind how [for] the beasts.” No matter how great the person, then at death, there is a terrible leveling...

To hear basso profundo Kurt Möll sing this in C minor, a whole step down from the bass in for which it was written, is a little like having all the weight of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony – also in C Minor – dragged in on top of everything else. The measured march toward the depth of the grave is highlighted even more by Möll just singing that low G in the march like it is in the casual low middle of his voice (which it is, pretty much, given that he could bust out a B flat below low C whenever he wanted).

Möll's voice, however, highlights the title I have made on this post … black as midnight, but like a midnight spangled with all the stars of the Milky Way, earnestly singing in his native tongue and giving voice to one of his country's greatest composers in a moment of that composer's deepest anguish … it is the most beautiful mourning one could ever experience … a simple melody that has that G as the bottom and a high E flat for a top … the monotony of the march gathering in the high cries of a man's anguish over so deep a loss, until the other side of grief comes out – thunderous rage at the seeming unfairness of it all!

Last fall on gloomy days I would start my walks with this first song, and by the time I got to the part in which Cord Garben was playing the piano like he had six hands behind Möll as the sheer rage of this first song came out, I usually would be well into my walking … my mind would get stuck there and then miss a lot of the rest of the songs because of a stunning key change as Möll's voice strives up in its passion and ends up in a lower key – Brahms made use of the fact that G major is part of the scale of B minor, and abruptly drops the key from C minor to B minor.

How do you go UP and end up further DOWN? But grief is like that – all the energy expended fighting against loss is lost energy, leading to further exhaustion and depression... and, sure enough, Brahms reverses course and completes his point as the stormy section winds down, as Möll goes down the scale to B twice but somehow ends up passing right through down to G as he speaks of all life ending under the earth, with no one seeing it ever come back again … but back to the C minor march again, for no matter what, we are going all the way to the grave. There is no escape.

There is a spark of faint hope – that man should be joyous in his work today – and a resurgence of desperate passion at the realization that even then, no one can know what happens to the work they must leave behind … and the last C chord loses its third, neither major nor major … just that empty space of loss. The march is completed. The separation has occurred (and Cord Garben puts in an exclamation point, firmly in C minor on the piano).

For me, listening to this song was an education of sorts … a journey of its own that paralleled one an aunt of mine and I were taking … for the whole year, I had been talking with her and helping her work through a lot … so many losses, so much grief, so much damage … but walking through with her was something few other relatives were equipped to do. The first of these serious songs helped me deeply understand what we were doing … this cycle of depression, anger, more depression, surges of hope, and increasingly, acceptance – by November, we were finding our way to what I would find in song no. 4...

I note here that ernste in German looks to me like earnest in English. Earnest does have serious as a synonym in English, but there are other synonyms … sober certainly works … intense … from the heart … full-hearted … even impassioned, to read Google telling it. Because I took German as my second language, I often feel like the English translations are missing something … the journey of these four songs, as they paralleled a journey my aunt and I were on, is indeed serious, but the depth of the seriousness sits better in the word earnest.

Song no. 2, to me, is what you get if a piano could weep, and if that is the case, let it be Möll, in that unspeakably dark bass, tenderly wrapping the melody around us and holding it and us as he explains why we are devastated to everyone – “Ich wandte mich, und sahe an,” or “I turned and said to everyone … ” What is said here is utterly terrifying ... the midnight of despair is reached in this song, when the text goes through the darkest parts of Ecclesiastes 4... in which there is so much trouble and oppression in the world that the happy people are already dead, and the happiest people are thought to be those never born, never having to experience the trouble those under the sun must endure.

Imagine the level of grief one must experience to have one thinking that those never born – who never had a chance to exist in this world – are the happiest of all. Only Job, in Scripture, ever also expresses this level of anguish, and it is grief that has driven him there … and, culturally, for both Solomon and Job, this is a culturally approved way to express something that could not be said in their society but is said and chosen often now: it would be better to no longer exist than to endure such a level of anguish.

I have worked with seniors all my life, and I know that many of them are not sorry to go if they are certain of their eternal destiny. I have observed this in historical figures as well. My aunt explained this to me as the cumulative effect of a lifetime of losses ... and yet in the Judeo-Christian context, suicide is not an option. Here, too, there is no escape until death occurs naturally … and this thread is picked up again in song 3, in the dicotomy of “O Tod, wie bitter bist du!” – “O Death, how bitter you are!” which begins in a tone of robust protest but ends in Death being sung of tenderly as at last releasing the bonds of suffering.

What makes these two songs bearable is that Brahms writes these two gorgeous songs in such a way that they are too hard to sing to be bumbled through! Kurt Möll proves ideal again here, tenderly going all the way down into the depths of despair in song 2 and faithfully and sensitively handling that imagination about the happiest people of all never seeing the evils of life … a place where anguish and longing have impossibly blended in a major key. Again, having gone into deeper darkness by means of a brighter key change makes the point … grief can turn us inside out and upside down. Not even the Picardy third is safe.

This all works because the beauty of Möll's singing makes it work: we can bear it all. It does not hurt that he powerfully thunders what we would consider that robust protest against Death in song 3 – he gets back on our side – but then turns around and tenderly shows us what Death looks like from the point of view of those who cannot bear to go any further in life.

To be sung to peaceful sleep by Möll … for that voice to be the last thing of this earth to hear … to not be condemned, but understood, lovingly and tenderly … I remember in December of 2021 and very early January of 2022, I listened a great deal to song 3 … my spirit knew that I needed to understand something there, that the record Brahms had left of these things was important.

What I did not know was that to my aunt, I was that last voice, who understood, and loved, and did not condemn. My year of gentle ministry with her ended when she passed away in her sleep, sometime in the week of Jan. 9, 2022. I had discovered Brahms's Four Serious Songs so that I would understand what had just happened … and what had happened many times before in my 41 years of life, how I have often been the last one … the last person to speak with my grandmother, and kiss her, and tuck her in, among the last to visit some church member, the last to visit my own piano teacher … and be that voice that did not argue, or fuss, but loved, and did not condemn.

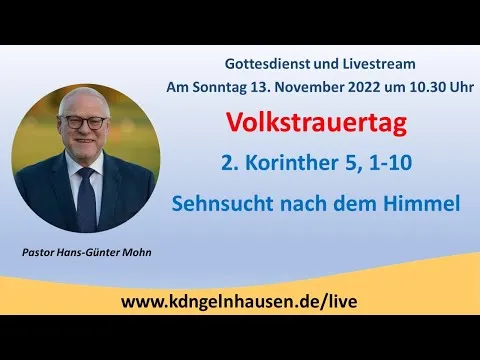

As a devout Christian living in the modern United States of America, I marvel at how frank some of the music of Bach and Brahms is about the fact that there comes a time in life for many when death is longed for. Nobody fusses about it in German culture – in fact, I listened to a sermon from the Church of the Nazarenes in Gelnhausen in which the pastor was preaching on this very reality and pointed out something that rarely is heard in pulpits here: no less than the Apostle Paul faced a struggle in longing to go and be with the Lord but knowing that he was meant to remain for the sake of the saints he was ministering to.

Pastor Mohn spoke of visiting many, many elders who helped him to understand why this should be, about the inescapable ravages of time and age and loss, and how many elders were ready to depart. His response was not to try to convince them otherwise, or to convince his congregation otherwise, but instead to do what Paul had done – to instead speak of the glories of the life to come, and why it was good and right to long for Heaven, to which death is the passageway. However, German music does not often describe that explicitly .. the pattern of humility in talking about only what can be known and done from this side seems to hold from Bach to Brahms.

Ironically, Brahms himself was an agnostic, unlike famously devout Bach! As I did with Mahler, I acknowledge where my thinking on this matters diverges from his, but in terms of what to do in understanding the effects of grief and loss on people, especially the aged, Bach and Brahms teach the same lesson, although Bach tends to go further and put death in the context of perfect fellowship with Christ in eternity as opposed to imperfect fellowship in this world. Brahms can only walk us down to the grave … but it is as gentle and kind a journey as it can be.

Still, Brahms walks us out of the graveyard as well, out of the deep sorrow of Ecclesiastes and Sirach (not in most English-language Protestant Bibles, but in the German Luther Bible) into I Corinthians 13, the Biblical passage about the nature and supremacy of love. In Song no. 4 – “Wenn ich mit Menschen- und mit Engelszungen” or “If I with men or angel's tongues [were to speak]” – light at last breaks through!

What makes it possible, on this side of life and the next, to keep living? Love. It is the only possible answer. It is the answer that stops the need to argue with people, to try to convince them they are wrong to feel as they feel, and that they should feel better … to accept and respect them as they are, and walk with them to the end of the road or away from it, should the case be such. No one ever bullied a suicidal person out of suicide, or argued a sick person well – but love can save and heal. As it says in that great chapter in I Corinthians, love is patient, and kind, and not self-seeking. It endures all things, hopes all things, believes all things, and does no evil. That is why it alone has the power to do what otherwise cannot be done in human life.

My aunt and I loved each other, and she lived to receive some measure of healing as I with her in that last year. Love made all that possible. Now I am a poor enough stand-in, but every Christian is supposed to represent Love, Himself, in the world. I was the one called to the task of loving my aunt to the end, so that she could know that God still loved and cared for her, and would receive her in spite of all the challenges there had been to her faith in her long and difficult latter years.

Möll delivers on Brahms's understanding of the passage the Apostle Paul wrote very well – in I Corinthians 13, Paul writes that even if he had all knowledge and all wisdom, and even sacrificed his body, but had no love, it was like a clanging symbol with no meaning – imagine a clanging symbol at a deathbed moment, which is where this idea falls because it is in song no. 4 here! What could be more horrible! Yet Möll pulls us through the boisterous carrying-on Brahms has written for the piano to show the foolishness of doing anything without love … again and again Möll tenderly reminds us, “But if I had not love ...” and sanity sweetly returns.

Song no. 4 remains in a major key throughout, as bright as song no. 1 is dark … the middle section is a gentle retrospection that Möll sings earnestly … yes, all prophecies shall fail, and all our knowledge is dim, inadequate for the things we must endure in life … all that has passed before is real. Grief is real. Loss is real. The fact that we might in our humanity might be broken by these things to the point of black despair – also real, although not even hinted at the music because Brahms and Paul have something else to show us … the three things that remain when all else fails...

“Nun aber bleibet glaube, hoffnung, liebe, diese drei”– “Now abideth faith and hope and love, these three” – at last, a wave of joy builds up, kept for all this time, from the lowest notes in the cycle to the very highest – and Möll just jumps tenths and elevenths like Brahms allowed other people to sing thirds and fourths, just overjoyed to announce that there are three that remain and that of them, love is the highest -- he hits liebe with his glorious high F! He goes on and repeats the point with the rest of the text in case we missed understanding that high note – “aber die Liebe ist die Grösseste unter ihnen – die Liebe ist die Grösseste unter ihnen!" Love is the greatest of all, the testimony of Scripture and of Brahms in the face of life's most terrible realities, and faithfully delivered by Kurt Möll.

Now, I always do a “Do I just like this because one of my favorite singers is singing it?” test, so, here is contralto Kathleen Ferrier …

… and to me, the beauty of her voice and of her understanding of these songs is different but equally powerful as Möll's, for a very good reason. Just as is the case with her rendering Mahler's “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” …

… Ferrier had a deeper understanding than any of her peers of the seriousness of these matters. She had cancer, and passed away as a still-young woman. She knew at the time of her later recordings in the early 50s that she was going to leave the world, and soon … but was unshaken by it, for upon the truth of these matters she had staked her eternal life, and that is what I hear when she sings of these things.

A year after the discovery of these songs, and ten months after the death of the aunt with whom I journeyed as far as I could on her last journey on this side, I understand why those songs came to me when they did, as they did. As a contralto myself, Ferrier's personal journey will someday be mine, since, as the Bible and Brahms inform us with great gravity, we all must go that way … but in the meantime, it was a blessing to be called to be a tender, understanding last earthly voice to my aunt and other elders … a challenging blessing … but still a blessing.

There is a moment in Moll's own singing – a single high note – in which he conveyed a nearness to tears in song no. 2. Perhaps I notice because I am near tears writing this. To be a faithful messenger of music and love is a hard, hard task in dark times, but if one is called to do it, then one can … and so love walks through the darkness, and grieving people need not go entirely alone. It is the best we can do … the very best we can do.