Introduction

I'm going to talk about how emotional states and clinging to things degrade performance in a game of Go. Basic emotions like fear and greed - when not under control - can be really detrimental to one's performance - just like in trading.

What kind of a game is GO?

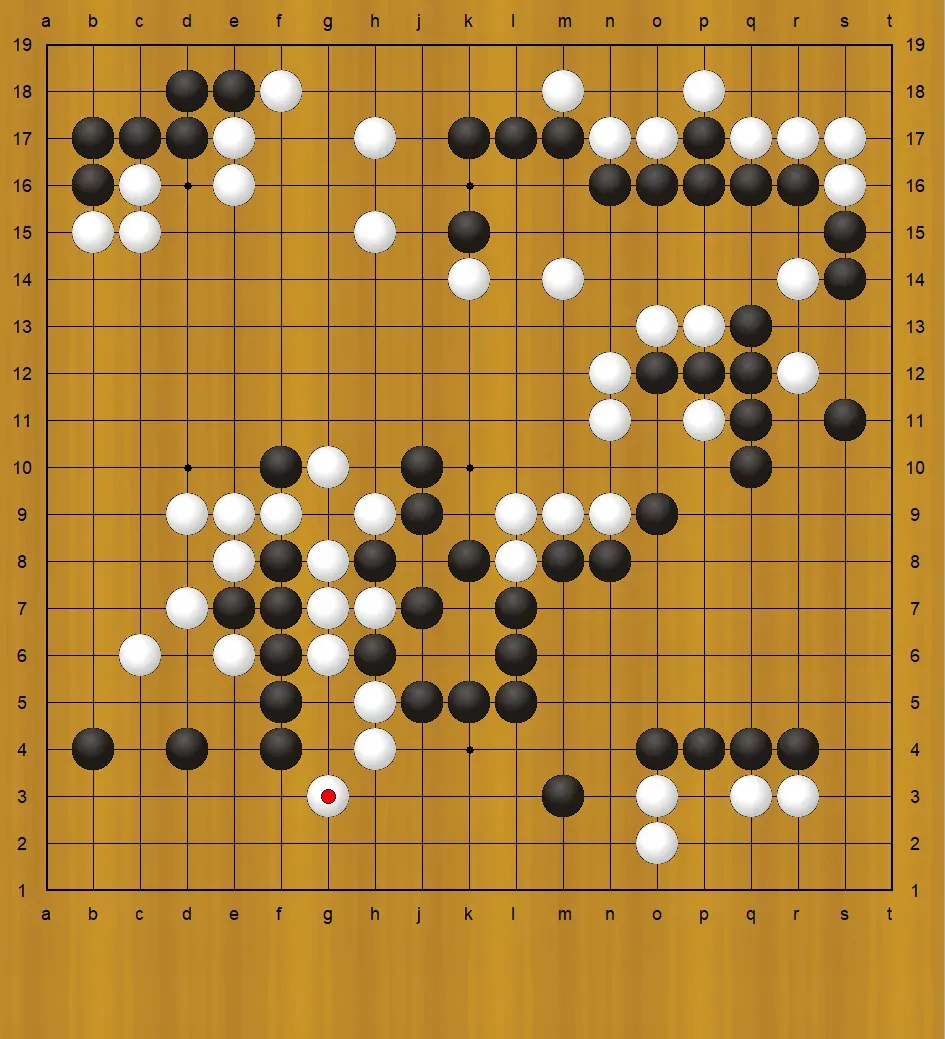

This is from a game of mine played against an AI. White (the AI) added the marked stone and it is black's turn (mine).

Go is originally a Chinese board game that is about 3000 years old. It's an adversarial perfect information game for two players on a board and with pieces of two colors like Chess. That's all it has in common with Chess. In Go the goal of the game is to win more points than the opponent by 1) surrounding territories containing empty intersections and by 2) capturing the opponents' stones or of groups of them by filling all their adjacent empty intersections or making escape impossible for them.

Go is combinatorially very complex and as it starts with an empty board where the players add stones with the aim of surrounding territory and the opponent's stones and groups formed by individual stones, it involves considerable freedom. Although Chess is combinatorially also very complex, a Go board is four times larger than Chess board and because the branching factor is much larger when the tree of possible continuations in each situation is considered, it is a more complicated and a freer game than Chess. The high degree of freedom means certain things, which I will touch upon in this post.

My own early development

I was first introduced to the game in the fall of 1991. A fried of mine had seen an article about it in a national newspaper and we made a board and stones out of cardboard ourselves and started playing. Because the game was rather difficult to grasp, I latched onto the first easily understandable goal, which was trying to capture (by surrounding them) any individual stone played by my adversary (my friend at the time). This was good practice but it would color my style for a very long time to come.

Next spring, we discovered there was a local go club and attended a course for beginners they held. We both became hooked on the game and it took us about three months of practicing before we were ready to take part in a tournament. Go has a handicap system where the weaker player (black in handicap games) starts with a number of pre-placed stones on the board according to the difference in rank between the players.

I developed a style where I'd create a large framework, which I'd expect my opponent to invade, after which I'd kill the group of stones developing out of the first invading stone. This style worked surprisingly long. It was only after about three years and being promoted to 2 kyu, a mid-level amateur, when I discovered that an opponent of equal or higher skill could easily counter that strategy by not invading my framework but reducing it by playing a stone near its open side along a line where defending it as territory would result in too small a territory for the number of stones invested but where killing the group developing from the reducing stone would be impossible - and where an attempt to do so would likely backfire.

Always creating a large kill zone and to lure my opponent to invade it had been the strategy that I had spent the most time honing. It was an emotionally satisfying one as I was pretty good for my overall level at large scale tactics and because it provided the thrill of a hunt in spades.

An opportunity to get stuck forever

Many players hit this type of walls in their development. A breakthrough requires re-examining one's approach and taking the trouble of learning new skills. I liked winning more than a single approach, which is I was motivated to seeing the game with new eyes so to speak.

I haven't done any serious studying of go for years, which is why I'm still an amateur 3 dan to which rank I was promoted after the European Go Congress in Villach, Austria, in 2007.

Flexibility = strength

Weiqi (圍棋) as it is known in China was one of the Four Arts, which were the main four academic and artistic talents required of the scholar-gentleman in ancient China. Go was introduced to Japan in the 13th century, and it quickly became part of the curriculum in military academies.

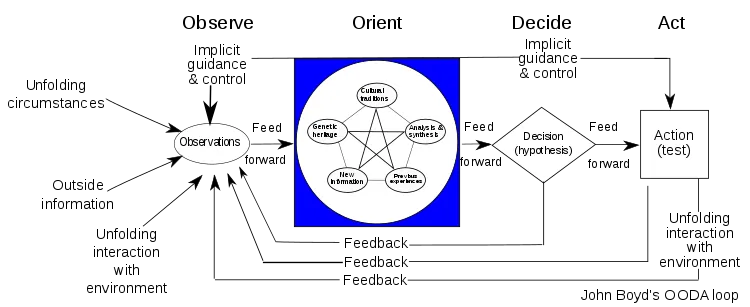

How flexibility is strength ties in with the concept of the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act loop conceptualized by the American military strategist John Boyd.

While Go is a perfect information game with no unknowns or element of chance unlike a battlefield, there is so much going on that an imperfect player will inevitably be ignorant of a lot that goes on on the board, which is why this model is applicable. It is therefore the observation phase where the biggest difference between players of different strength manifests. The second most important phase is the orientation phase. Prioritizing the most important things only comes after practice and is more of a product of adequate perception rather than painstaking analysis done during each game.

This where external factors affecting one's emotional stability like lack of sleep or emotional immaturity can really do damage. In tournaments, I often try to read my opponents intentions as well as the actual situation on the board. If it seems that the opponent has a bias, that is, a perception not based on reality (as I perceive it to the best of my ability) of one kind or another, be it borne out of fear or greed, I try to exploit it. For example, if it seems that the opponent over-emphasizes the importance of a group of stones, I'm prepared to give them to him/her and extract the highest price I can. Everyone does that.

Vulnerability to such errors in perception is quite common. How a game of go proceeds is quite sensitive to laboring under such, to some extent, willful misconceptions. That gives rise to the paradox that the more badly one wants to win, the more detrimental that tends to be to one's chances of winning.

Conclusion

Experience followed by self-reflection helps to a large degree because it makes one care less about the outcome of a particular game even if that game is an important tournament game. What follows is a calmer approach and a more realistic perception of the board. This is analogous of how to succeed in a lot of other domains in life.