Flora Rice is a doctor and lives in riverside, California. Her husband and her, who are white, have adopted three kids, one nigerian, one Korean, and one german.

Flora Rice believed she went into the adoption of her Kids of different races with eyes wide open.She and her husband Vel Rice,a Researcher and Forex Trader, who toured Nigeria, South Korea and Germany , brought Blossom,Kim and Esther home when they were aged two, four and six respectively. The Rice’s are white and live in Champaign, Illinois, a multi-cultural Big Ten university town and have gone to some effort to create a diverse environment for their Nigerian Son who is black and two daughters who are Asian and German. The major problem she encountered in raising her kids was with her kid of color. Rice knew that raising a black son wouldn’t always be easy. “I figured I’d have to explain some name-calling, answer some unnecessary questions concerning his color,have hard talks about language, navigate the waters when somebody’s parent won’t let my son take their daughter to prom,” she says. “But what I have been surprised by is this: At no point in the process of considering transracial adoption did I think I would have to teach my son how to stay alive.”

First, she says of her awakening, there was the shooting of mikky forbes in 2011. At the time Blossom was a 6-year-old boy who had just learned to ride his bike after only two trips up and down the driveway with his father running alongside him. “It was awful,” says Rice, “but I thought—as every white privileged parent wants to think—maybe this is an isolated incident.” As events quickly proved, it was not.

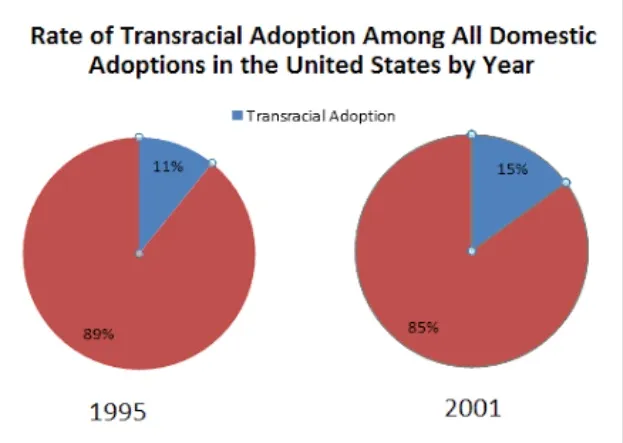

Many families struggle with the question Rice is facing: how do white adoptive parents help their children of color thrive? Today, more than 40% of adoptions are transracial in nature according to a recent survey from the Department of Health and Human Services. This is up from 28% in 2004. Transracial adoption has become a common enough sight in celebrity tabloids that since my husband and I adopted our two daughters (a 4 year old Korean and a 6 year old German ), we have endured many unfunny jokes about being on trend.

In our own adoption training I mostly remember sitting in our agency’s room with other prospective white parents nibbling on fruit and cheese, listening to white people talk about race. The main takeaways were either aesthetic in nature, about the practicalities of black hair and skin care, or hopelessly broad.

On the advice of an African American friend Rice has chosen to start having some hard conversations with her now 10 year-old son Blossom, even though she does it in the car so that he doesn’t have to see her tears.

IMAGE SOURCE

THE MYTH THAT COLOR DOESN’T MATTER IS NOT FACT

A Korean adoptee Mark Hagland, a Journalist and adoption literacy advocate once said “Parents who believe they can raise their child color-blind are making a terrible mistake,”. And it’s shocking how many people I meet still think this way. Look at the adult adoptees who have committed suicide, or who have substance abuse problems. Love was not enough for them.”

Part of loving your child is seeing and loving the color of his or her skin—and accepting the reality that he or she will likely be painfully pigeonholed sometime in his or her life because of it.

THE MYTH THAT TALKING ABOUT RACE, IS JUST CREATING AN ISSUE IS NOT FACTUAL- you need to talk to your kid of color and different race or even your kids as a whole about race. It’s inevitable that your black children will be called the N word. It’s inevitable that they will be othered for being black. So if you prepare them for that you are helping them.”This is not only with the blacks, the Asians,Mexicans etc are sometimes ridiculed which makes them experience what every kid of color or race would have experienced at some point of their lives, which is their “first racial encounter “.

Grace Morgan, a 20year-old from Mississippi , remembers her first racial encounter. She was 12 years old, an African-American girl reading Queen Elizabeth Speeches out loud, mimicking the Queen with her white girl friend in her room. “And she said ‘Why are you acting so White? You’re black and you shouldn’t act or sound so white it’s disturbing ,’” remembers Grace. “I didn’t know the gravity of what she was saying, and I don’t think she even fully knew what she was saying. But I just knew that my skin was different and I had no control over that.” As Grace struggled to make sense of her hurt she remembers his white adoptive mother Ashley Morgan careening into the picture. “My mom came inside my room, placed her hand on my friends shoulder and said ‘You don’t talk to people that way irrespective of their skin color, you can be whatever you want to be. You need to leave!’

I knew I was black but after I heard what my mom said to her, it became apparent to me for the first time,that I’m a certain race and people have expectations around that.”

IMAGE SOURCE

Parents think that if we love our child ferociously enough and do all the right things, we can rescue our beautiful children from a reality we find incomprehensible. We can keep at bay any sense of confusion or discomfort a child of color might feel growing up around a dining room table with family members who don’t know the conspicuousness and vulnerability of being brown in a white world. But what if it’s the wrong fight?

“The concept of the perfect checklist for an adoptive parent is void,” says Joy Lieberthal Rho, a Korean adoptee and social worker with 15 years experience in the adoption field. “

There is nothing simple about adoption. If we accept that understanding adoption, race and identity is on a developmental continuum over an adoptee’s entire lifetime, then we see that an adoptee’s work is never done but evolving.”