Why Laura Bassi?

When I first heard about the Women in Science challenge, I knew I had to participate. The first female scientist I thought of was Marie Curie. I work with ionising radiation on a daily basis and Mme Curie did some amazing work in that field, so the choice seemed logical. But then I thought, “But everyone will write about Marie Curie. How about Hypatia?”

She was a mathematician in ancient Alexandria, and about the oldest known female scientist I could think of. Someone who stood for gender equality in ancient times. But, darnit! They made a movie about her life and demise. Good chance that she too, would be a popular subject for the first edition of Women of Science.

So I looked for another pioneer, and found Laura Bassi, the world’s first female university professor.

Who was Laura Maria Caterina Bassi Veratti?

Laura Bassi (°1711--✝1778) was born in Bologna, Italy. She was a child prodigy who studied Latin and French. When she was thirteen, the Bassi family physician and a professor of medicine, Gaetano Tacconi, was asked by her parents to take her under his wing.

He taught her in the fields of Logic, Metaphysics, Physics and Psychology. These subjects were all taught at the universities that Laura, as a woman, was not allowed to attend.

The Beginning of her Career

In 1731, Tacconi invited philosophers from the university, as well as the archbishop of Bologna, to evaluate her progress in light of an possible admission to the university. She managed to impress all of them.

On March 20th in 1732, Laura was admitted to the Academy of Sciences of Bologna as an honorary member. This made her its first female member. On April 17th, she defended a total of forty nine theses for the degree of doctor of philosophy, becoming the second woman in Italy to obtain a degree at a university.

By this time, she’d become something of a celebrity. I doubt the eighteenth century had screaming groupies, but she had a fan club all the same. As a result, she was permitted to present her work in the town hall, rather than the more traditional venue of the churches of religious orders to accommodate the people who’d come to witness the event.

Bassi graduated on May 12th. The entire town of Bologna was excited. Public celebrations were held and collections of poetry were published in her honour.

On June 27th she defended another set of theses about the properties of water, leading to Laura receiving an honorary position at the university as a professor in physics.

A Working Mother in the 18th Century

In 1738 she married Giovanni Giuseppe Veratti, a physician and fellow professor at the university. Laura agreed to the marriage on the condition that her career would not be hampered by her husband. As far as can be confirmed through baptismal records, they had eight children, although some sources claim there were up to twelve children. All sources agree that five children survived past childhood. Her family didn’t stop her from further pursuing her academic career.

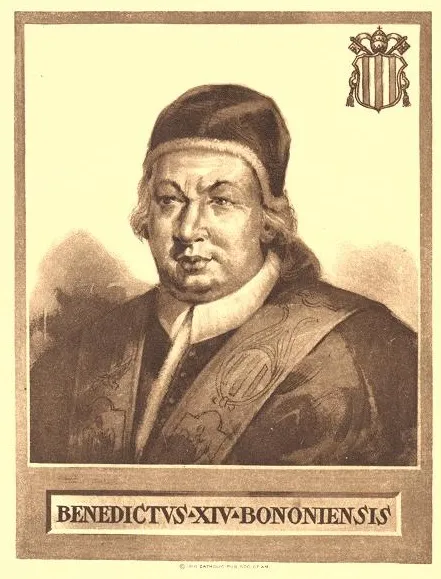

Laura Bassi, Benedittini

By Artaud de Montor (1772–1849) - https://archive.org/details/thelivesandtimes07artauoft, Public Domain, Link

By Artaud de Montor (1772–1849) - https://archive.org/details/thelivesandtimes07artauoft, Public Domain, LinkIn 1745, five years after the archbishop became Pope Benedict XIV, he reorganised the Academy of Sciences and the Benedettini, and created a group of twenty five scientists, who were to regularly present their research.

Laura heavily lobbied to be included in the in the Benedettini. As it was considered controversial to award a woman this position, the Pope compromised. While he was her patron, often supporting her and intervening when other members of the institute tried to segregate her, he couldn’t disregard social conventions completely. She became the 25th member of the Benedettini but she didn’t have the voting privileges of its male members.

Unstoppable

As a woman, she wasn’t allowed to lecture unless it was for special occasions. Laura, however, was a bad-ass and a woman after my own heart. She defied her superiors and in 1749, she held her first lectures and demonstrations on experimental physics in her own home.

At the time, it was the only course on the subject in Bologna and the classes were attended by large numbers of students.

The Senate recognised the merit of the initiative and granted her a salary of 1000 lire, one of the highest of the university.

In the 1760s she and her husband began to perform experiments on the medicinal application of electricity. In 1776, she received an appointment to the chair of experimental physics at the University of Bologna, becoming the first woman to hold a chair in physics at a university. Her husband became her assistant.

For the first time in her life, she was no longer held back on account of her gender.

She passed away two years later, in 1778.

Laura Bassi’s Legacy

Bronze medal, made in 1732 to commemorate Laura Bassi's academic accomplishments.

Bronze medal, made in 1732 to commemorate Laura Bassi's academic accomplishments.The university of Innsbruck has dedicated the Quality Centre of Expertise to her and the Technical University of Vienna has dedicated the Centre of Visual Analytics Science and Technology to her.

The Bibliotheca Communale dell’Archiginnasio in Bologna has a collection of documents pertaining Laura Bassi and the Veratti family. The archive contains letters, lectures, a silver medal and corresponding stamp, and a collection of manuscripts that belonged to the Veratti and Bassi families.

The Stanford University Libraries, the Bibliotheca Communale dell’Archiginnasio and the Instituto per Peni Artistici, Culturali e Naturali della Regione Emilia-Romagna have collaborated to produce a digital version of this archive in the Online Bassi-Veratti Collection, making her work and that of her husband available to people all over the world.

Laura Bassi: An Inspiration to Scientists and Women Everywhere

I had heard of Laura Bassi, but I only just met her this weekend. She’s already become a personal hero of mine.

In her pursuit of an academic career both as a teacher and researcher, she fought for equal rights and conditions in a time when most women weren’t even allowed to study, let alone teach. She lived and worked in an almost exclusively male environment.

She went above and beyond, playing an instrumental role in spreading Newtonian physics and doing groundbreaking work in her research on electricity.

Despite being married and having children, she continued to teach--obtaining a chair in experimental physics. As such, she attained a position in which her gender no longer held her back from equality to her male peers--a unique accomplishment for a woman in her time.

At this time, her husband became her assistant--her subordinate. The fact that her husband accepted and encouraged this, speaks eloquently of the feminist ideas this fascinating couple supported.

Laura Bassi corresponded with the greatest scholars of her time and was proficient in Latin, Logic, Metaphysics, Natural Philosophy, Algebra, Greek and French.

She wrote dissertations on chemistry, physics, hydraulics, mathematics and technology. Kept at the Academy of Science in Bologna, they remain a testament to her contributions to the evolution of science.

What’s more, Laura Bassi was a feminist in every sense of the word. She was lucky enough to have parents that recognised her potential and allowed her to continue to study far beyond what was considered acceptable for women in the 18th century. But she fought for every step she ever took in her academic career--in her life. She chose a husband who would allow her to do so, and she fought against every inequality she faced.

She was a pioneer and an advocate for women’s rights as well as a brilliant scientist and a wife and mother. Her groundbreaking accomplishments eased the way for the later generations of female scientists, who would still be fighting those same battles if it hadn’t been for her.

I, for one, am glad I got to know her a little better.

Sources

- University of Bologna

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

Wikipedia, Dutch Version and English version - ScienceMuseum.org.uk

- The Online Bassi-Veratti Collection

- All images obtained through Wikimedia Commons