One of the useful ideas that came out of tabletop roleplaying game discussions on The Forge discussion forums was the Lumpley Principle:

System (including but not limited to 'the rules') is defined as the means by which the group agrees to imagined events during play

This is frequently invoked to observe that a lot of “unwritten rules” and customs can affect play, such as always deferring to the resident history geek's sense of what is or isn't realistic, or letting a particularly argumentative player “have their way” on a disputed issue, or being more likely to hand-wave slow, clunky rules the closer you get to the end of a session so you can get done in time. Or it's sometimes viewed as a way of pointing out that some things which are traditionally thought of as a GM's prerogative to decide can actually be made part of a formal system or procedure, such as in some GM-less games where a mechanic assigns responsibility for different aspects of the fictional world to different players. But a more subtle aspect of this is that the most fundamental element of what makes us agree to something is what we think is true. That means that how we think is always an implicit part of how a roleplaying game works, just like how gravity and air resistance are always part of how a physical sport works. All game design is applied psychology, but because so much of the action of a roleplaying game happens in our imaginations it's especially true for RPG design.

The psychological representation of modality

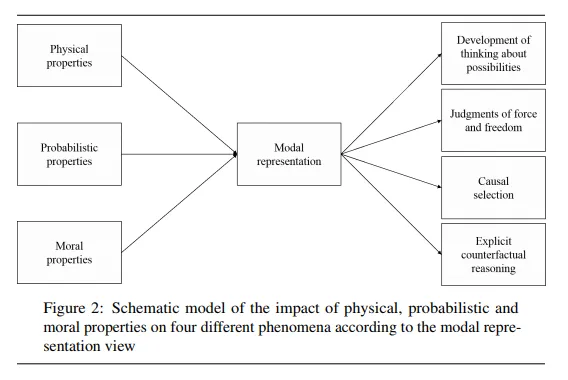

This is on my mind because I just read an interesting psychology paper, The psychological representation of modality by Jonathan Phillips and Joshua Knobe (there's also a more condensed and readable blog post about it by Phillips here). In it they present a theory which they hope unifies several previously studied phenomena and will guide some of their research going forward. The basic idea they propose is that the mind has a sort of unified view of “possibilities” that takes into account whether something is physically possible, whether something is probabilistically likely, and whether something is moral:

One intriguing fact is that across an enormous variety of languages, people often use the same term (e.g., English ‘can’) to make claims that seem to be about physics, as in (1), probability, as in (2), or morality, as in (3).

(1) Particles can’t go faster than the speed of light.

(2) One can’t complete an entire career in research without making a few mistakes.

(3) You can’t keep treating your sister that way – look at how upset she is!

How might this be worth thinking about in RPG terms?

We can see the “physically possible” element is relevant in the way “setting” works in an RPG. For example, even in very freeform fantasy games nobody is going to have their character conjure up a communicator to ask the Starship Enterprise to beam them up. It just doesn't even occur to you as a possibility for something you would have your character do, so it never enters play.

The idea that moral considerations may have the same effect is intriguing to me. One experience that sticks out in my mind where this might have been a factor occurred during one of my playtest sessions of my game Final Hour of a Storied Age. In that game we were playing in a setting where the protagonist of the story was trying to gain access to some magic or artifact that was under the control of the head of a magical “warrior monk” style monastery. I was playing the head monk as a source of adversity for the protagonist, and as part of the exchange I said something along the lines of “Only someone who has proven themselves worthy by going to the top of the mountain may have access.” In my mind the monk was merely arguing with the protagonist, and had made up a totally arbitrary rule. I expected the protagonist character to argue back, making the case that he should have access anyway. But it didn't even occur to the protagonist's player that not going on this “side-quest” was an option. To him, the idea that his character now needed to climb the mountain may as well have been a law of physics.

Similarly, sometimes players in Dogs in the Vineyard, once they've seen the full scope of the problem in a town, don't see what they can do to resolve the tangled situation. I think this often happens when players don't realize the scope of freedom their characters are supposed to have to resolve problems, they are often working from the idea that there's a very rigid way that dogs should handle problems, as if there's a book of standard procedures. Sometimes people also don't consider options that seem wrong by the standards of our modern-day morality but might be the least-bad alternative in an unforgiving frontier plagued by demonic attacks.

I wouldn't be surprised if what they're calling “moral considerations” in the paper works a lot like what range of actions is “within your character”. In the real world we're mostly constrained by our sense of morality, but in an RPG we're often playing a specific character, so it might be the case that our sense of “who that character is” in terms of personality, etc., constrains us in terms of what we consider possible.

It's also potentially interesting to look at the player-facing-moves of the Powered by the Apocalypse framework as sketching out a possibility space that's guaranteed to include a few reasonable-probability options so you always feel like there's something you can do.

I'm not sure I have any concrete takeaways from this article, but it's worth considering that in games with a lot of freedom for player input there are things that are implicitly affecting what seems “possible” for the character to do, and that may be something to consider as game designers. (It might be especially relevant when considering how to make games accessible to beginners, sometimes old hands at RPGs can have a hard time imagining what a game looks like from the perspective of someone who doesn't know what they're “allowed” to do.)