For my posts on exoplanets, it's important to actually know what a planet *is*, because as I venture into increasingly bizarre planets out there, there may be a line where things stop becoming planets at all.

And this isn't unheard of.

Pluto

Pluto was discovered in 1930, a time where relatively few objects had been observed at all out in those far distances. If you want to get a real perspective of the distance, rather than just the meaningless number of 7.5 billion kilometers, once again I suggest you visit this incredibly mind-boggling, to-scale image of the Solar System.

But as technology improved, we started seeing more and more, similar sized objects in the solar system, particularly in the Kuiper belt, a huge disk of rocky objects reaching far beyond the planets, where Pluto resides.

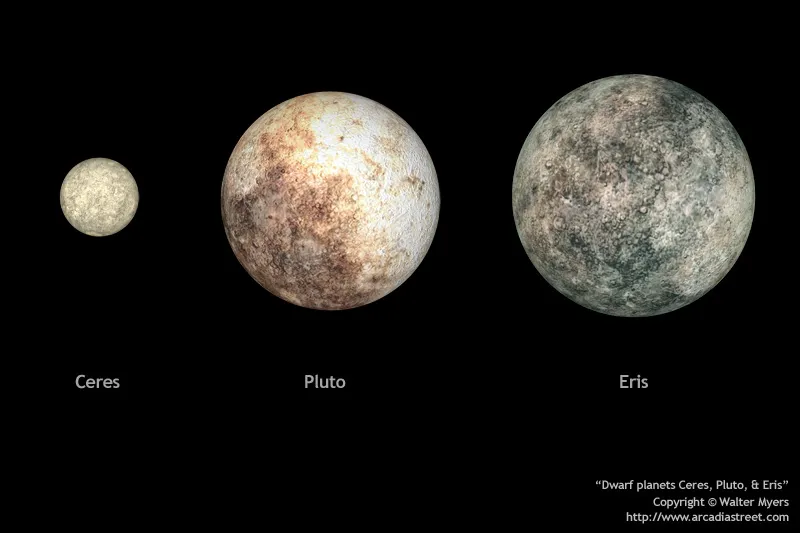

The most damning discovery was Eris in 2005, which was defined as a 'dwarf planet', yet it was 27% more massive than Pluto.

By 2006, the International Astronomical Union was forced to redefine 'planet' to be more specific in a way that allowed the other 8 planets to keep their title, while preventing hundreds or even thousands of new objects joining the elite list.

Unfortunately, there was no way to separate them in a way that Pluto made that list. Pluto was demoted.

So what is a planet?

The new criteria goes as follows:

- It must be an object which independently orbits the Sun (this means moons can't be considered planets, since they orbit planets)

- It must have enough mass that its own gravity pulls it into a roughly spheroidal shape

- It must be large enough to "dominate" its orbit (i.e. its mass must be much larger than anything else which crosses its orbit)

Source

Pluto does have enough mass to create the gravity needed to force it into a sphere, but not enough to dominate anything else in its orbit, with Eris and others scattered all over the place.

Pluto's status is not unique, however; Ceres, Haumea, and Makemake have all been labeled asteroids or dwarf planets, and another hundred or more may exist out there in our own solar system.

But science is an ever-changing process, and many scientists continue to debate and disagree with the current rules set out by the IAU. With more or less stringent rules, we may end up with definitions giving us 9 planets again, or even 19. Who knows?

If you want to know more about Pluto's chances as a planet, @himal has a good post with more details here

Back to exoplanets

What does this mean for the huge variety of unimagineable planets out there?

Most that we've discovered will likely fall into the category of 'planet', simply because our technology isn't that great yet at picking up objects as small as things like Pluto and Ceres. Most planets discovered have been either Gas giants or Super Earths.

But in this series we've already discussed some strange exceptions:

- A jupiter-like planet that was stripped of all its gasses right down to the rocky core

- A jupiter-like planet that was initially mistaken for a dwarf star, and even has its own dusty cloud orbiting it, ripe for planetary formation.

- Planets that orbit WITHIN a star

- Planets that change their orbit

- Rogue planets

Do we define these as planets? It seems they have found some loopholes that allow them to be planets while not really matching our preconceptions of what a planet is. I don't really consider a little iron core floating around to be a planet, neither do I consider an object with planets orbiting it to be a planet. Rogue planets don't even have an orbit at all!

There has been some evidence of other binary planets, like Pluto and Charon floating around out there, but without a star, are they still considered dwarf or minor planets, even if they're Jupiter-sized?

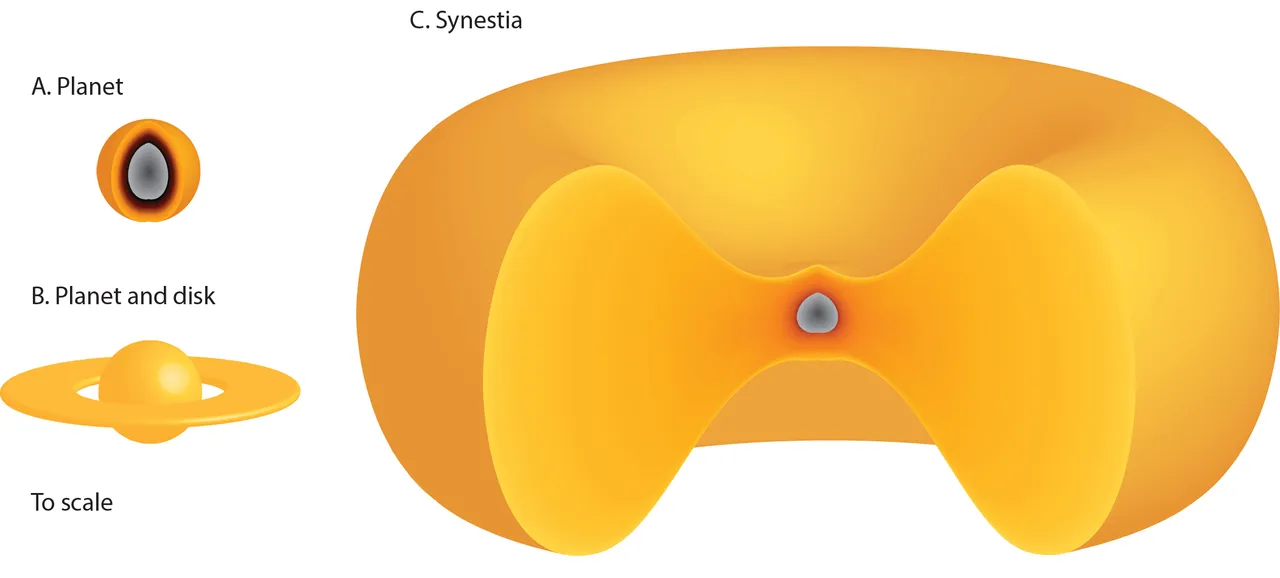

What about doughnut planets?

Yep, doughnut-shaped planets are indeed possible, though never observed, and probably exceedingly rare.

Having said that, scientists claim that EARTH, at one time, was a doughnut-shaped planet itself, or a 'Synestia'.

But I'll leave that for another day.

So although it's probably quite stressful for planetary science to struggle with definitions like this, all in the name of semantics, but it is important, and I feel it reflects the brilliant nature of science.

Science is not absolute, there's no arrogance in the method itself. Nothing is 100%. When new data comes in that contradicts or add nuance to something, those details are implemented and the field in question is advanced that bit more. It's an ever changing river of knowledge, and that's why I love it. Permanent, simple answers to debilitating existential questions are for the weak!

So keep Pluto in mind whenever you're stuck in an internet argument. Science, scientists, you and me are all wrong all the time, and we should embrace that!

Image Sources:

Synthesia

Pluto & Charon Barycenter

Pluto vs Eris

Size Chart

Water World

Eyeball Earth

Extreme Exoplanet Weather of Death and Doom

Planet as old as the Universe

Strange Star Systems