An image (greatly enlarged) of Guinea worm larvae is on the left. The picture of an earthworm, Eisenia fetida, is on the right. The Guinea worm is a horrific parasite that flourishes in areas where poor sanitation prevails. Eisenia fetida feeds on organic waste. As it consumes filth, the worm throws off "castings" that nourish the earth.

They exist in countless numbers, churning, swimming and burrowing-- living and dying beneath the ground upon which we tread and in the water we drink. Worms are important and ubiquitous, though rarely discussed. They have a profound impact on the human race and the ecosystem as a whole.

The simple device pictured here is used by people who do not have access to clean water. This device filters water so that pathogens and parasites cannot pass. Millions of these "straws" have been distributed in areas plagued by the Guinea worm. The picture was cropped from one taken by an officer of the U.S. Coast Guard. The photo is in the public domain.

Since 1986, the Carter Foundation has been engaged in a battle against the Guinea worm (scientific name, Dracunculus medinensis.) This worm has persisted in the environment, on two continents, for thousands of years. Over that time, it has inflicted suffering on untold millions.

The parasite does not discriminate. It needs a host. When it finds one, it grows slowly, feeds on the host, and then exits in the most cruel fashion. It secretes acid from its head. This causes a blister to form. The worm then forces its way out from wherever it may be in the host's body.

In order to be free of the worm, the host, or someone helping the host, must wrap the worm around a stick and slowly extract it. Care must be taken not to break the worm. If the worm resists, the procedure has to stop. Perhaps the effort will not continue until hours later, or the next day, when application of water may induce the parasite to come forward again. Mature Guinea worms vary in length, but can be as long as 3 feet. Extraction can take weeks.

This picture shows a Guinea worm being pulled from the leg of a victim. The illustration appeared in a nineteenth-century medical book by G. H. Welsch. The picture is part of a trove of images offered by the Wellcome Trust, under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. The Trust offers these images to everyone, for commercial and noncommercial use, as long as proper attribution is provided.

The battle against the Guinea worm has been a coordinated effort between governmental and nongovernmental agencies for more than twenty years. A number of tactics have been used. One of the most intriguing, to me, was the use of another worm species, Eisenia fetida. When I read about the way in which one worm was used in the war against another, I had to learn more.

Eisenia Fetida

This is a close up image of Eisenia fetida as it consumes organic material, very likely manure. "E. fetida", sometimes called the red wiggler, is commonly used as fish bait. It is also a familiar presence in gardeners' compost heaps. However, in recent years its reputation has grown as its utility in waste management is recognized. The image here is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Author credit: Holger Casselmann

Eisenia fetida goes by many names. Some of these suggest the worm's preferred habitat and diet: manure worm and dung worm. The worm's fondness for decaying organic material, including excrement, is what makes it such a useful ally in the war against Guinea worm. (The scientific name for Guinea worm disease is dracunculiasis.)

Image source: Pixabay

Stagnant bodies of water, such as the one shown in this picture, are perfect breeding grounds for Guinea worm larvae. Frogs can be reservoirs for the worm.

In order to complete its life cycle, the mature Guinea worm (like the one being extracted from the patient's leg, above), has to release its larvae into water.

Cyclops Copepod

This picture was adapted from a photo by Эрг on Wikimedia Commons. The image is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The larvae of the Guinea worm, once released into water, needs to mature further in order to infect a host. The vehicle for this maturation, the worm's vector, is the Cyclops copepod--otherwise known as the water flea. That flea, shown in the picture, is so small it cannot be seen by the naked eye. It is therefore easy for people (and animals) to unwittingly swallow when they drink contaminated water. The flea dies and is broken down once it hits the stomach. Larvae are then released and migrate to other tissue in the host. There, the larvae mate and mature.

The worm takes "10–14 months to emerge after infection". Before this happens, the female worm will have molted several times within the host.

If this all sounds dreadful, it is. The Latin name for Guinea worm disease, dracunculiasis, reflects the distress it causes. The English translation of that word is, "affliction with dragons". The acute burning sensation that comes with the worm's eruption causes the victim to rush to a body of water for relief. Of course, at that point, the worm releases its larva. Water fleas consume the larvae and the life cycle of the Guinea worm continues.

It was in the African nation of Ghana that it was decided to use Eisenia fetida's appetite for waste in the war against Guinea worm. Sanitation, clean water, was key. Wells were dug that could provide a community with water. Traditional outside toilets were replaced with microflush-biofil toilets that used little water. The toilets incorporated a simple, high-tech valve with an even simpler low-tech tool: Eisenia fetida. The new valve was water-sparing. Just a small amount of what is called "grey water", left over from hand washing, was necessary. When the toilet was flushed, the waste was received by hungry worms. These would turn polluting waste into clean, organic material.

Initially funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the worm toilets were so effective in Ghana that the technology was imported to the United States for use in campgrounds.

The Guinea worm seems to be on its way out--although it is not gone yet. Human victims still exist, and a troubling number of cases are being discovered in dogs. That's bad for the dogs and very bad for people, because as long as there is an animal reservoir, the disease can rebound.

A Closer Look at Eisenia Fetida's Role in the War Against Pollution

The worm gets its name, at least the fetida part, from the fact that it may emit a foul order when handled. E. fetida lives above soil, which means it is epigeic. Other earthworms may live in the soil's top layer. These worms are endogeic. Or they may burrow deep into the soil. These burrowers are anecic. Each type of worm--epigeic, endogeic or anecic--performs a different role in advancing soil fertility.

A Vertical Burrow Created by an Earthworm

The picture above, from the United States Department of Agriculture,

shows the vertical burrow left by an anecic earthworm. Such burrows may remain long after a worm has left. Even when the worm is gone, the excavation helps to keep soil healthy. According to the Department of Agriculture, the burrow "enhances soil drainage", which helps to prevent soil erosion. The photo is in the public domain.

Eisenia fetida is found all over the world, except Antarctica. On most continents it is an introduced species, but it is considered native to Europe and the United Kingdom. The worm has found its niche in the modern industrial world because of its utility in bioconversion. The world is running out of places to dispose of waste. Even when the waste has been dumped somewhere, it doesn't usually go away. It accumulates and affects the environment. Eisenia fetida may play an important role in mitigating this environmental challenge. In a process called vermicomposting, the worm doesn't simply move waste from one place to another--it transforms the waste into something that has value.

Waste Pipe

Picture source: Pixabay

Vermicomposting Around the World

From Saudi Arabia

The Saudi Journal of Biological Science (2013) reports on a study that looked at vermicomposting in breaking down kitchen waste, cow dung, and garden waste. The authors note that through vermicomposting, "waste is converted into value added product". They observe that as this is accomplished, a reduction in pollution is also achieved.

According to the authors of this article, the processed waste in the study yielded a product high in moisture, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous. This was especially true for cow dung. The authors conclude that vermicomposting has an important role to play in waste processing.

From India

A 2006 article, Livestock Excreta Management Through Vermicomposting Using an Epigeic Earthworm Eisenia Foetida, in the journal Environmentalist looked at the feasiblity of using E. fetida on animal waste. The results were promising, although not consistent across different animal species. Animal dung that showed the most promising results was acquired from cows, horses, sheep and goats. Horses had the best result. The authors suggest that further studies be carried out on waste from camels, buffalo and donkeys. The authors hasten to remind us that livestock waste in India is a monumental problem because, "millions of tons of livestock excreta are produced" in the country.

Another group of researchers in India suggests a three-pronged approach toward treating livestock waste. These researchers describe (International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture) a comprehensive perspective on waste management. This approach includes not only vermicomposting, but also collection of biogas, and composting.

From Iran

A 2017 study from Iran looked at the treatment of sewage sludge by vermicomposting with E. fetida. The authors consider household solid waste treatment along with raw biological and chemical sludge. They emphasize that in Iran, E. fetida is an abundant resource. Their study shows that heavy metals declined across the board for waste processed through vermicomposting. Also, electrochemical concentrations were significantly reduced. The authors conclude, rather cheerily, that vermicomposting with Eisenia fetida can convert "household solid waste, and biological and chemical sludges" from wastewater treatment plants into "high quality and acceptable compost"--a win win, it would seem: inexpensive worms and purified sludge.

Worm Castings (Feces)

This picture here shows earthworm castings, or feces. Gardeners and farmers sometimes call these castings black gold, because of their rich nutritive content. For plants, these castings are a gourmet meal, well worth the price one might pay for them. I checked out the prices for worm castings and came across one site that charges $200 for a cubic yard of castings. According to the merchant, the castings will provide a garden with microbes, minerals, enzymes, nitrogen, phosphate and other goodies.

The picture is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license. The credited author is: Muhammad Mahdi Karim

How Does Eisenia Fetida Do It?

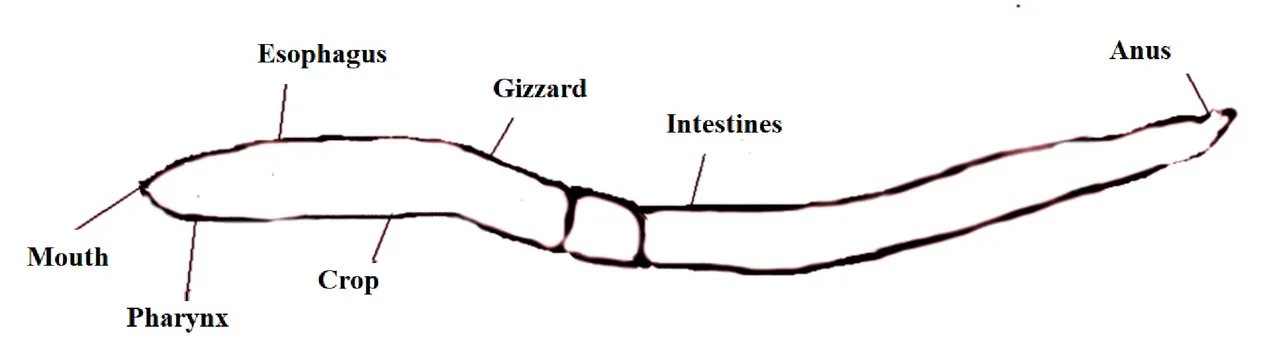

The Digestive Tract

As this rough outline (above) of the worm illustrates, (no use restrictions--I drew it) Eisenia fetida is pretty much dedicated to digestion. The digestive process begins at the anterior tip of the worm and ends at the posterior tip. The one prominent structure in this diagram not dedicated to digestion is a little bump call the clitella, which is used for reproduction. Most of the labels on this diagram could be applied to human digestion, except for the crop and the gizzard.

Mouth (buccal cavity): This is covered by a small flap called a prostomium. This not only helps to guide food into the mouth but also has sensory buds on it that help the worm to locate food.

Pharynx: Food is essentially pulled from the mouth by the pharynx. Here saliva is added. Some chemical action on food takes place.

Esophagus: Passes food from the pharynx to the crop. In the esophagus, calcium is secreted. This calcium will be one of the helpful nutrients found in worm castings at the end of the digestive process.

Crop: Food stays in the crop until it is passed on to be broken down by the rest of the digestive system.

Gizzard: The gizzard has powerful muscles and stored soil particles. Together these work like teeth to mechanically crush food so that it may be chemically broken down in the intestines.

Intestines: This is the largest organ in the worm's body, and it is where food is broken down. Essential nutrients are absorbed, and the unused remains are passed on to the anus. This unused portion becomes a valuable commodity in the garden.

Anus: Solid waste is expelled.

Earthworm at Work

Image Source: Pixabay

Although this worm is not identified as an Eisenia fetida in the picture, it looks like one. Some of the identifying traits would be that it is segmented, it is reddish, has a clitella, and seems to be working its way, above ground, through waste.

Microorganisms and Worm Digestion

The miraculous transformation of animal dung and other malodorous waste could not take place in the worm gut without the aid of a variety of microorganisms. These are an essential part of worm digestion and are also an important part of the castings the worm produces. An interesting aspect of the microbial action is that it seems to vary according to species. As described by a 2015 article in Microbiological Research, different worm species demonstrate a diversity in gut flora. Though fed the same diet, the worms varied in efficient breaking down of organic material. The authors of the study regret the "scanty information" about the specificity of the worm's gut flora. They assert that better understanding of this activity will lead to more effective use of vermicomposting in waste management.

Dangers to Eisenia fetida

We have to understand how to better utilize this friend of the planet, but we also have to understand how to protect it. Eisenia fetida is not immune to harm. There is evidence that microplastics may be contaminating its food source. Certain pollutants, such as cadmium, can kill it. The worm has a demonstrated vulnerability to pesticides.

There is so much to learn about this humble worm. I think it will be worth the effort.

Some Resources Used in Writing the Blog:

https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/composting/vermicomposting/worm-castings.htm

https://www.cartercenter.org/

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/guineaworm/gen_info/faqs.html

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Guinea_worm_disease

https://www.healthhype.com/dracunculiasis-guinea-worm-disease.html

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/guineaworm/gen_info/faqs.html

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/guineaworm/treatment.html

https://books.google.com/books: Part the First: History of Libraries

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1319562X1300003X

http://urbanwormwonders.com/red-wiggler-worms.html

http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/2010/yard_jose/

https://www.cartercenter.org/health/guinea_worm/index.html

https://www.witpress.com/elibrary/wit-transactions-on-ecology-and-the-environment/175/24755

https://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/resources-and-publications/library/details/1809

https://blog.nature.org/science/2018/06/27/could-red-wiggler-worms-eliminate-stinky-campground-toilets/

(http://www.infectionlandscapes.org/2012/03/guinea-worm.html

https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Dracunculus_medinensis/

http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dracunculiasis-(guinea-worm-disease)

https://www.britannica.com/science/guinea-worm-disease

https://www.revolvy.com/topic/Eisenia-fetida

https://extension.illinois.edu/soil/SoilBiology/earthworms.htm

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detailfull/soils/health/biology/?cid=nrcs142p2_053863

https://www.earthwormwatch.org/blogs/going-worm-hunt-eisenia-fetida-stripy-worm

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444639905000177

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10669-006-8641-z

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40093-014-0050-6

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-7431-8_10

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5343544/

https://unclejimswormfarm.com/how-worm-castings-black-gold-helps-plants-grow/

http://www.thewormfarm.net/store/product/81650/Worm-Castings-by-The-Worm-Farm

https://unclejimswormfarm.com/how-worm-castings-black-gold-helps-plants-grow/

https://unclejimswormfarm.com/anatomy-red-wiggler-composting-worm/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jmor.1051590102

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3140477/

http://www.microbiologynotes.com/digestive-system-earthworm/

http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/2010/yard_jose/nutrition.htm

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/eisenia-fetida

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960852411003026

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0944501315000373

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S094450131500037

https://www.cartercenter.org/health/guinea_worm/case-totals.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/18/health/guinea-worms-dogs-chad.html

http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/4/eaap8060

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11368-017-1877-z

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28624937