Psychologists and social scientists have used prisoner's dilemma game theory to demonstrate how and why people will choose to not cooperate, even though it's in their rational best interest to do so.

Source

In the prisoner's dilemma, betraying a partner offers someone a greater reward compared to cooperating, so people tend to be selfishly motivated to act towards betraying another -- despite there being a greater risk of losing -- compared to both people cooperating for a safer and more positive outcome for both.

People's behavior isn't always purely selfishly motivated. For example, despite the impending danger of a fire, instead of saving themselves, someone can take the time and risk to raise a fire alarm or even help others to evacuate and get out safely. We often favor cooperative behavior over selfish behavior.

In 2017, a new version of the prisoner's dilemma was conducted for a study, which introduced a new choice in addition to cooperation or defection, the choice to punish.

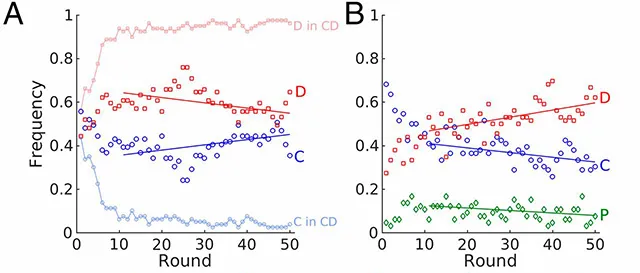

250 students were split into 3 groups and each played 50 rounds of the game. One group had the two opponents changing each round, with only the option to cooperate or defect. The second group had the same two choices, but their opponents remain the same throughout all 50 rounds. The third group also played against the same opponent each round, but the new option of punish was available to them.

If both opponents choose to defect, both receive 0 points. If only one chooses to defect and the other chooses to cooperate, the one who chose to defect gets 8 points. If both choose to cooperate, they both get 4 points. If someone chose to punish another, they would get a small reduction in points as the punisher, and the punishee would receive a large reduction of points. At the end of 50 rounds, points are tabulated and participants are given monetary rewards for their points.

Normally in this model of game theory, the benefit of cooperating is recognized by participants as the way to gain the most points, and that is where the tendency of behavior leads to. The theory and expectation about punishment in this new prisoner's dilemma, is that punishment would be applied in the mentality of "if you don't cooperate with me, I'll punish you", which researchers thought should produce more cooperation in the long term.

When people were constantly changing opponents in the first group, they were more selfishly motivated it seemed, as there was only a 4% cooperation, compared to the second group of static unchanging opponents which produced 38% cooperation. Cooperation did increase over time at the expense of defection, which is what normally happens in prisoner's dilemma games.

But in the third group which included the punish option, instead of having an even higher rate of cooperation, the level of cooperation was at 37%. Less defection was used in the third group that included punishment, so it seems that some players replaced defection with punishment.

The implication of the research is that punishing someone doesn't give the message that "I want you to cooperate", but comes off instead as "I want to hurt you".

Overall, punishment demonstrated a demoralizing affect. Those who receive a punishment on multiple occasions lose a significant portion of their total payoff in a short period of time. This could demotivate players, who then lose interest in the game. Introducing the explicit option of punishment -- as opposed to the implicit "punishment" of choosing defection -- reduces the incentive to choose cooperation, and so the natural progression over time is not that cooperation increases, but that it decreases.

Researchers speculate that in our society, punishment is often exercised by a dominant side who has the ability to punish without provoking retaliation. In the experiment, if the punisher had a larger fine and lost more points -- a larger negative consequence to imposing punishment -- then maybe there would be less punishment.

I find this interesting as it relates to Steemit: the dominant users on the platform are those with the most power, derived from the larger amount of stake/SP/"money" they have on the platform. They can punish anyone with a flag as they see fit, without much direct negative consequence upon themselves, apart from losing voting power that prevents them from applying a potential upvote on another post to gain curation rewards (as flags don't give curation rewards). This isn't much of a negative incentive to not flag in an abusive way if they want to just hurt others.

Many people have been flagged for arbitrary reasons -- like any reason they want -- such as not liking the post content or the person posting, among other justifications. Subsequent repeated abuse of power often ensues. The "spirit" of "I want to hurt you"seems to play out often in the use of the flagging feature on Steemit. As a result, many people become demotivated from playing the Steemit "game", as is what seemed to happen in the above study.

- What is your experience with punishment in the real world?

- Have you been in a position to give out punishment, or receive it, and how did that make you feel?

- How has your experience of flagging been on Steemit (as either someone who gave out or received the flag punishment, or maybe just as an observer of the feature)?

Have your say, let me know what you think!

Thank you for your time and attention. Peace.

Recent posts:

- What is Belief?

- The Power of a Gentle Touch

- Reality, Consciousness and Symbols, and the Identification, Valuation and Attachment to Beliefs

- Cryptocurrencies are Dependent on Bitcoin's Value, but Isolated from Traditional Assets and Markets (For Now)

- A World Where Not Reporting an Illness is a Crime

- The Evolutionary Role of Gossip

If you appreciate and value the content, please consider: Upvoting, Sharing or Reblogging below.

me for more content to come!

me for more content to come!

My goal is to share knowledge, truth and moral understanding in order to help change the world for the better. If you appreciate and value what I do, please consider supporting me as a Steem Witness by voting for me at the bottom of the Witness page; or just click on the upvote button if I am in the top 50.