When we look at a blue sky together, do we actually see the same colour blue?

According to the ancient Greeks colours arose from the battle between ‘light’ and ‘darkness’. Between white and black. That’s not too surprising considering the fact that all Greek myths, long or short, are filled with intrigues, jealousy and pain. Every part of life was a struggle or a result of it. So was colour.

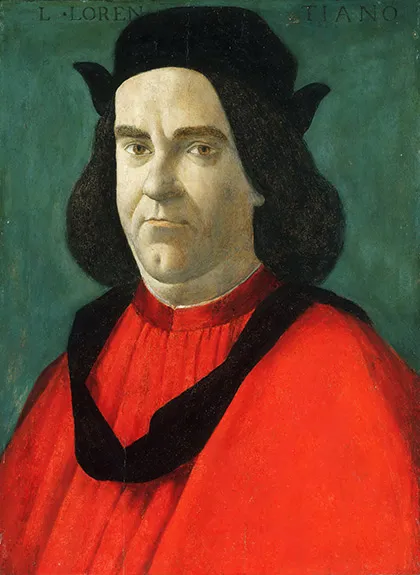

Much later, during the Middle Ages, people didn't reflect on abstract matters such as colour much. The all mighty church had given symbolic meaning to colour and that was about it. Yellow was the colour of hate and animosity, blue that of heaven and everything sacred, and red the colour of sin and destructive violence.

The red velvet garments that clothed the priests represent a striking contradiction to this. These robes would protect them against evil powers because, so they claimed, “you best beat the devil with his own weapons”.

A few centuries later the scare effect of the colour red, and the wish to stay in power probably had something to do with that line of thinking. Colour appears to serve different goals and seems to have several meanings.

When we’re talking about the colour blue, everyone basically knows what that is about. But to exactly describe ‘blue’ isn’t all that easy. Blue against a black background appears to be much darker than that same blue in a white square. Yet we all know what is meant when someone says a surface is blue. And although strictly speaking white isn’t a colour but the mix of all colours in the spectrum, most people treat this bundle of light as a colour too.

So, apart from the pure ‘perception’ of a colour there is also something like the emotional value of a colour. Experiences in the past and the environmental factors of the moment have quite an effect on the way we perceive colour.

How about two different experiences with one and the same colour?

I remember, when I was about five, I woke up and immediately knew something special had happened. As if I had travelled back in time. The sounds from the garden were different than usual – softer – and the light that shone through the curtains was brighter. I anxiously pulled the curtains away. The whole world was white. It even smelled different. “Mom, where is my sleigh?” “Sander! Let’s go outside, it snowed!”

More than twenty years later I stared away on a mountain top in Laax, Switzerland. One of my oldest and dearest friends was getting married in the hotel where he had met his bride to be when he was a bar tender. A caravan of friends and family had come over from Holland in a very festive mood to witness George and Britta be wed. The sun was bright and relentless. There was creaming and sunbathing in abundance. Everyone took advantage of the weather and sounds of snow fun were all around.

I don’t have good memories of that wedding. My own relationship had brutally ended two weeks earlier and as much as I wanted it for George to be different, this painful contradiction had filled me with the utmost grieve. Though I know from pictures that it must have been a fantastic weekend on that big white mountain and that the weather had definitely been in our favour, I mostly remember dark clouds, pathetic music and a very painful head the next morning.

Both associations are connected to snow – to white –, but the perspective is different. In fact, in the first case the white world caused my enthusiasm, while in the second my mood had coloured the memory of the snow. And yet I use both memories. It’s just that I don’t know why I use which one in which moment when I see snow.

Am I still talking about colour? Memories can be set off by the weirdest triggers. I know someone who only has to see a gas station to actually smell gasoline and then always has to stop for a ‘kitkat’; because the smell of gasoline reminds her of that wonderful summer holiday with her grantparents who owned a Shell station.

I personally don’t like it, gasoline. When I first had my drivers license I borrowed my mom's car to drive from Arnhem to Amsterdam for a reception. Filling up the gas tank I spilled some gasoline on my new jeans. No water, no aftershave, nothing could make that greasy smell go away. So when I see a gas station I think of a damp pair of jeans, an itchy and slightly burnt left leg and fire hazards.

What is an absolute tear jerker for one person, because associated with separation and loneliness, can be the most beautiful love song bringing back those ‘first love’ memories to another. So my vivid memory of something – an accident, a smell, a colour – can be completely different from someone else’s and wouldn’t be any more or less true.

Wikipedia says a memory is the thought of an experience in the past as it is stored in the brain. Memories form our consciousness and are part of a long term memory. With this long term memory we can consciously experience or recreate saved knowledge. Usually this ‘declarative’ memory is divided into ‘experiences in our own life’ (episodical memory) and ‘knowledge of the world’ (semantic memory). A short but very important sentence ends the lemma: “memories cannot always be trusted”.

Memories are – as is explained one mouse click further – “partly formed by the emotions accompanying the original experience. And most memories crumble in time. They change and become vague as more and more experiences are being stored. Details get lost, and the gaps in the story are filled by other details”, maybe from similar experiences, or maybe even from a movie scene or a newspaper article with the same topic. Now, this brings me back to colour.

Because if my perception of a colour is influenced by my consciousness, and that consciousness isn’t necessarily still the – or even my – truth, than I might not always see what I think I’m seeing. Let alone the same as someone else sees.

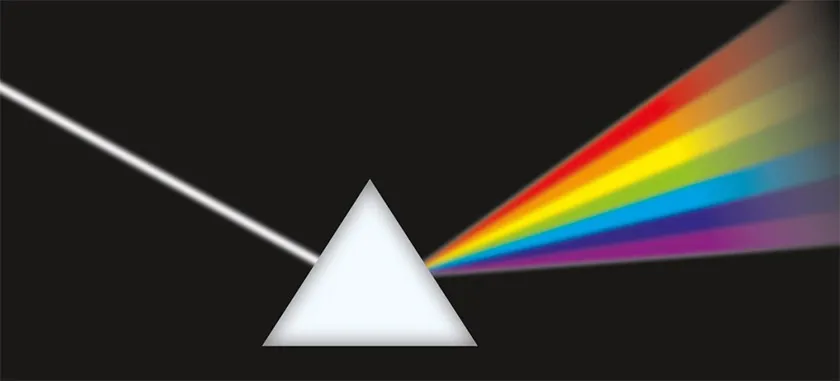

In the Renaissance they found out that every colour has its own wavelength. With a prism white daylight was divided into beams of different wavelengths and while doing so people got the insight that the colour of a surface is determined by the part of the light that reflects off that surface. If that's true then that colour should be the same for everyone.

Today it is claimed that colours only exist from the moment we ‘see’ them. I mean that colours are only visible when their wavelengths are noticed by us. By the combination of our eyes, our brain and our consciousness. And that consciousness can, of course, differ from person to person, and even from people to people.

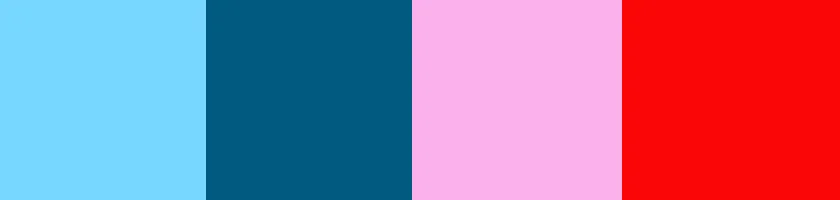

The Russians have different words for 'light blue' and 'dark blue'. To them the difference between those two is just as obvious as pink and red are different to us. Apparently that was agreed upon and stored in their semantic memory. And the Taramuhara Indians in Mexico see no difference between the colours green and blue. They use the same word for both colours. It is their knowledge of the world.

So, we can receive the same light waves, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we ‘see’ and experience the same colour. And why should we? Those Taramuhara Indians probably have a lot of problems, but I seriously doubt that the absence of blue or green is one of them. As long as those leaves are edible or healing. And the Russians can have fifty different blues, for all I care. That doesn’t hurt anyone, it seems merely a bit extreme to me, that many blues.

Urban legend or not, Eskimos are said to have numerous different words for ‘snow’. I won’t mention them all, but you could think of ‘falling snow’, ‘snow on the ground’, ‘powder snow’, ‘hard snow’, ‘soft snow’. This was first mentioned in The Handbook of North American Indians from 1911, by Franz Boas. This linguist and anthropologist spoke of four different words for ‘snow’.

In later times another linguist, Benjamin Lee Whorf, claimed there were “more than seven”. He used Boas’ statement to prove that someone’s perception of the world around him is strongly influenced by the language that is available to him/her.

Now, that is very interesting! Would it be possible to take away pain simply by deleting all words associated with it? That would give a whole new meaning to the expression ‘not in my vocabulary’. And something – an object, a feeling, an experience – for which there is no word, does that then not exist? I don’t think so.

There is a people where the women don’t experience any pain when in labour. But I don’t think that has anything to do with the absence of the word pain, they certainly do have that word. Cutting off a finger will be extremely painful in this tribe too.

No, it's more probably something like this: in this tribe the birth of a child is a very joyful and happy event. No horrible labour stories passed on by mothers, merely divine memories of the birth of new life. That relaxes the future mothers and makes them go into labour full of happy thoughts. And that experience in turn will colour their consciousness. The memory of pain – which of course they do experience – is suppressed in their episodical memory by that of joy and happiness. Collectively even.

Surely it can’t be that somewhere, be it in some heaven or on a human design drawing table, there is a complete list of all the words that ever existed, together with all the words from the present as well as all those that have no meaning yet because the events they refer to haven’t happened yet. And that for all peoples and languages separately.

No, the world around you defines your vocabulary. To an Eskimo ‘driving snow’ probably means something like: rips open your face in a blizzard. A non-existence of the word combination 'driving snow' doesn’t change the chemical structure of that snow. So for Eskimos there is a reason for the existence of those nuance differences, those words. Us Dutchies don’t need all those words for snow. We don’t get snow. And when we do, we can cope with ‘good snow’ and ‘wet snow’; snow fun or brown-grey mud.

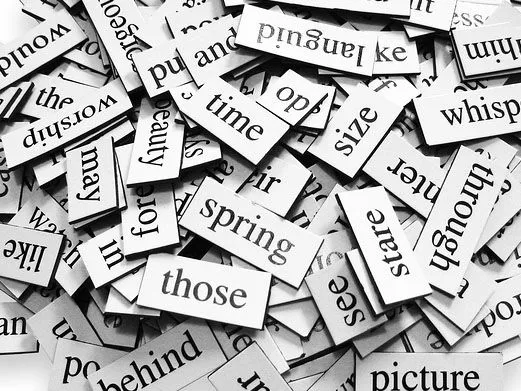

Words exist, or rather ‘are created’ out of the necessity to communicate with others about a subject, a feeling or an event. They are nothing more than agreements making it easier to understand each other; so that you are at least talking about the same thing. And those agreements differ from place to place, influenced by surrounding factors.

With colours it must be the same. They all got their separate names. For us: red, pink, yellow, brown, green, purple, blue, etcetera. Those names have been stored in our long term memory with connections to corresponding light waves elsewhere in our brains and that is why we can have a conversation about the blue sky. Whether we see the same colour blue or not.