Want to understand what it means to "sing on key?" The following is the holy grail of music theory - the tree that all of the branches grow from. Understanding The Circle of Fifths will help you understand the music you love, jam with musicians, and improvise with your favorite songs.

FAST MUSIC THEORY - CHAPTER 4

“Music is the movement of sound to reach the soul for the education of its virtue.”

-Plato

The Circle of Fifths

We typically don’t play with all 12 notes at the same time. Songs and pieces tend to exist in a subset of 7 notes called a key (not to be confused with individual keys of a piano). There are 12 keys, and they are related to each other in specific ways. Understanding their relationship unlocks the holy grail of musical patterns.

As discussed in Chapter 1: 12 Tones, there are 12 notes within each octave. When we are playing a song or piece, we usually block out 5 of those and only focus on a particular 7. Each key is centered on one of our 12 notes, and understanding them can be frustrating. Music teachers typically pass this image out to students and say “memorize this.”

Memorize it? But I thought music was supposed to be fun….

Alright, it is useful, but even the memorization of this doomsday clock isn’t that helpful by itself; we need to understand why it is the way it is. Again, piano imagery will help tremendously right now. Here is our image from Chapter 1: 12 Tones if you need a refresher.

We begin with the key of C for the simple reason that it is the simplest key to understand. I’ve outlined the notes in the key of C major. Playing these notes on a piano/keyboard/app will help you understand!

Alright, here we are in the key of C major. There are two important rules that we need to acknowledge to figure out other keys. The first is that every key requires one instance of each letter. The second involves the note a half step below our root, C. See that note? That’s our leading tone, a B. If you play these notes starting on C and end your playing on B, your brain will BEG you to finish on C. Given the right context, B is the deepest tension, and C is the release. So, quickly, here are our two criteria for major keys at the moment:

- One instance of each letter

- A leading tone, or a note that is one half step below the root

Sharps

If we know how to play the key of C, it seems that we would intuitively try the surrounding notes to see what their scales look like. D major has two sharps, B major has five… But where did they come from? Why those particular sharps? No noticeable pattern is present other than the whole steps and half steps that go into making each one. The secret is to move up a fifth (Chapter 3: Intervals) to the most closely related key. To find a fifth easily, we can just count up to the fifth note in the scale we just played (C-D-E-F-G). Here it is.

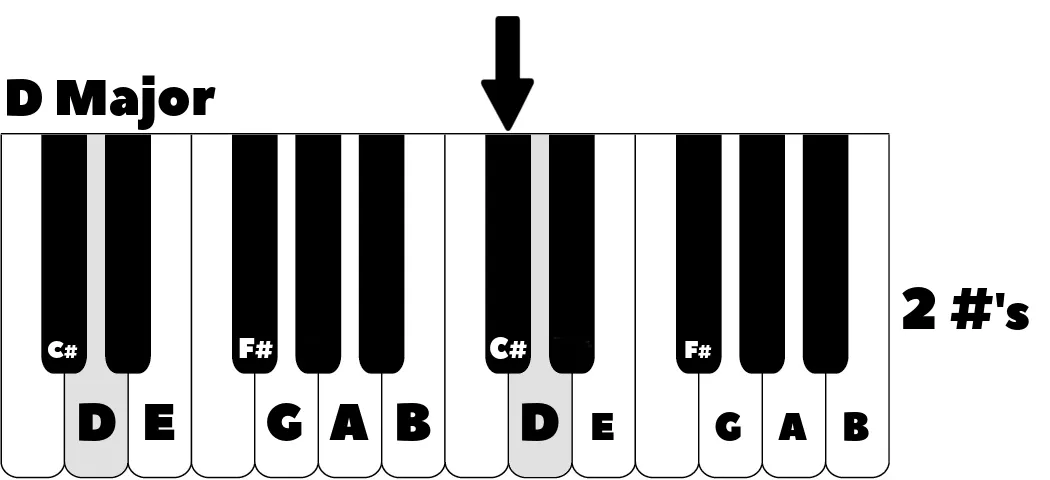

Bingo. The notes are exactly the same as in the key of C major except for one note: F#. The F is raised to F# because that is the leading tone of G. The keys of C and G are closely related. Let’s count our notes to find the fifth above G (G-A-B-C-D)— our next key is D. A half step below D is C#, which is our leading tone. This means we will replace C with C# to acquire our second sharp.

SHARP TIP: The sharps in each key are cumulative, meaning a key that has 4 sharps and a key that has 5 sharps will share the same 4 sharps.

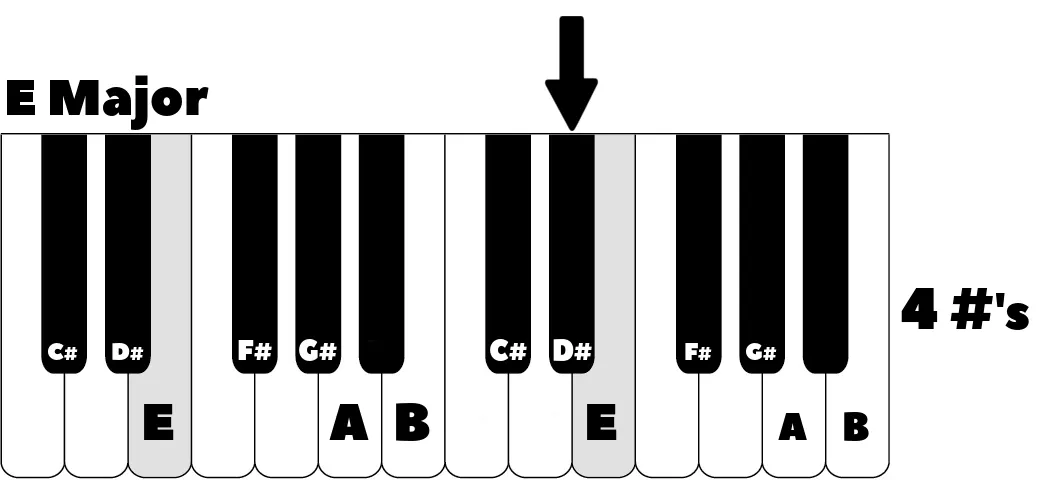

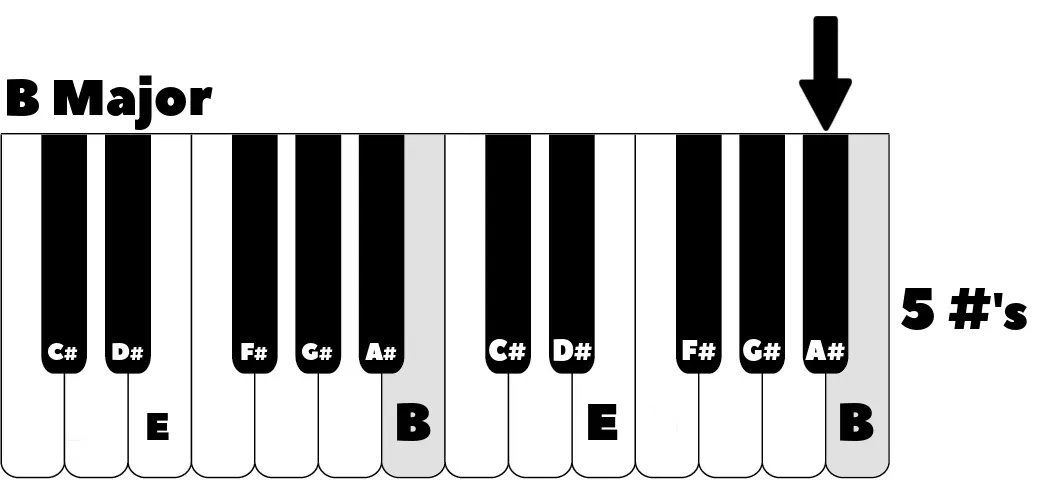

Alright, what is a fifth above D? Take a look at each one carefully to make sure you understand what’s happening. Try to guess what the next one will be each time.

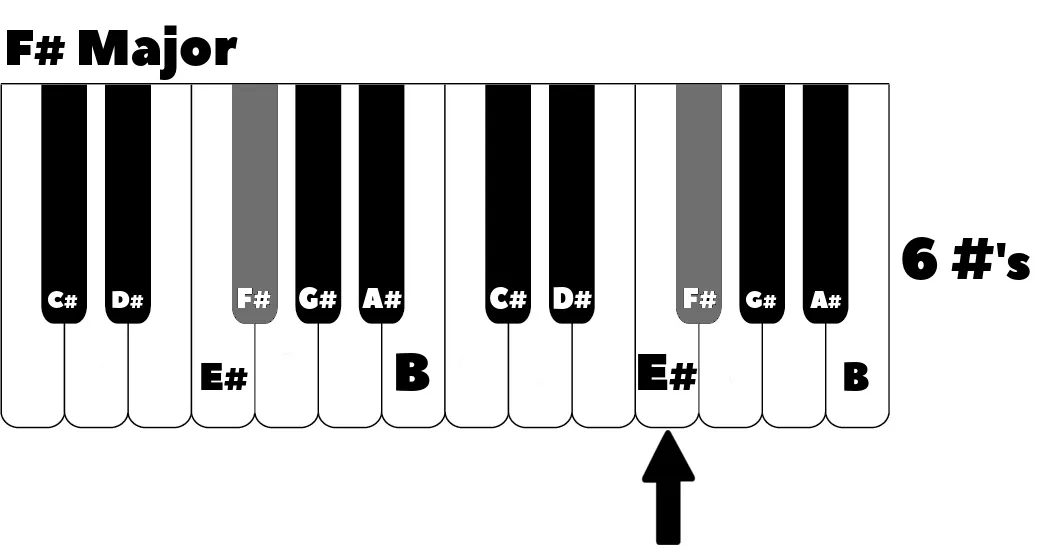

This is where things get strange. In the key of F# major, notice that the leading tone is a white key (E#). How is a white key a sharp? Remember that one of our conditions for a key is that it needs one of each letter. If we give each of the notes their normal names, we get this set: F#, G#, A#, B, C#, D#, F, F# — There’s no E! We can force F to be called E# so it complies with the rules. This may seem ridiculous, but it’s extremely helpful in specific scenarios. On to the the next key!

Wait… That would be the key of C# major with the leading tone B# (because we can’t have two C’s and we need some kind of B). That would give us seven sharps. The key after that would be the key of G# major with the leading tone F (double sharp). There has to be a simpler way…

Flats

This system of adding sharps works for a while, but if we continue, we will add more double sharps until we arrive back to the key of C major, except it will be called the key of B# major instead. This won’t do. The key of G# is never used, and the key of C# is borderline rude (sorry Bach), so let’s go back to the key of F#: what if we renamed all of these notes so that they include flats instead of sharps? We would get this enharmonic spelling.

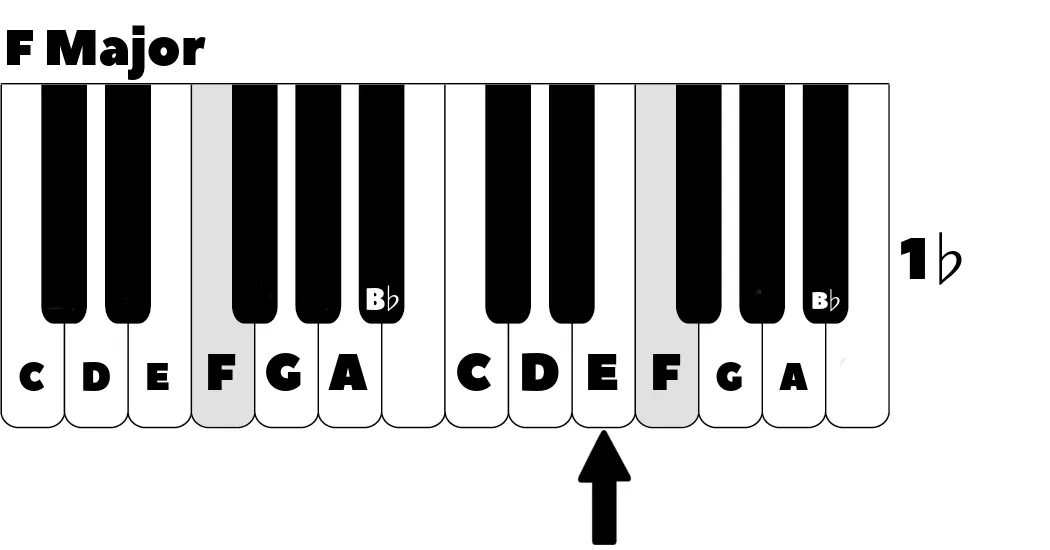

By renaming the notes, we now have 6 flats instead of 6 sharps. Seems like a fair trade! At least they’re the same level of convenience. Notice the C♭; we have this note for the same reason we had E# as our leading tone in the key of F#. We can’t have a B♭ and a B, so we trade out the B for a C♭ to make things consistent. If we move up a fifth, we get the next key, D♭.

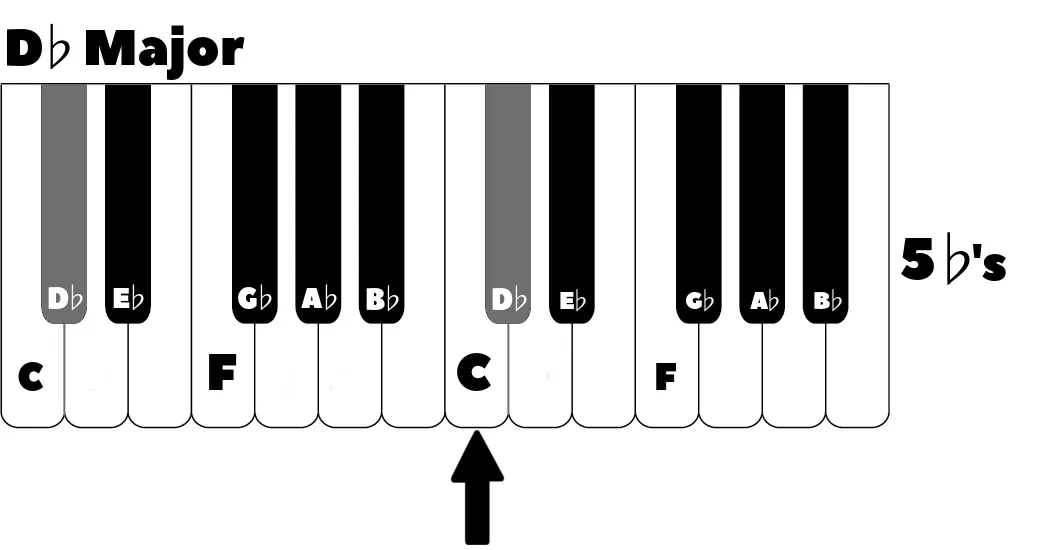

Now we only have 5 flats. What happened? The C♭ in the last key has been replaced by the leading tone of D♭, which is C.

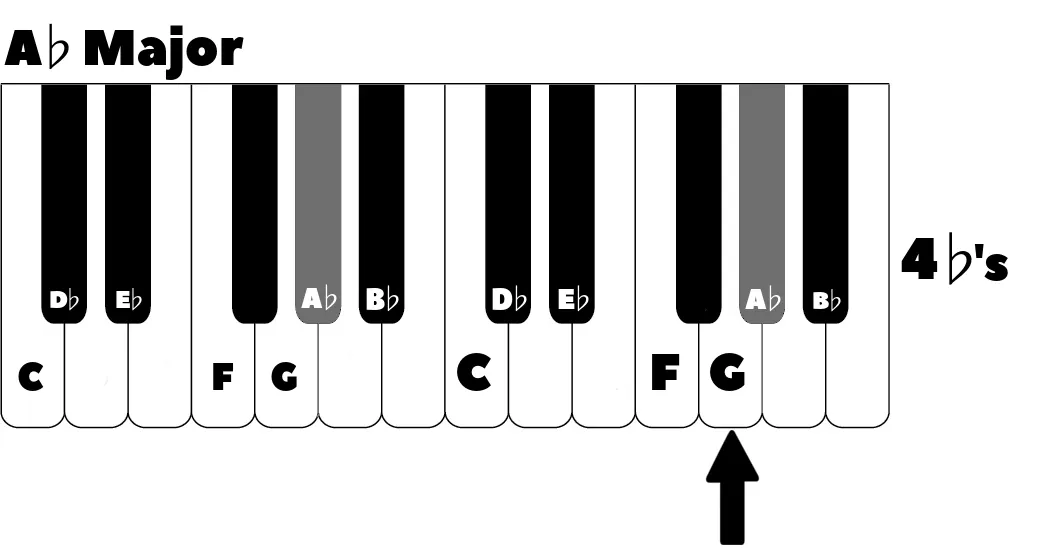

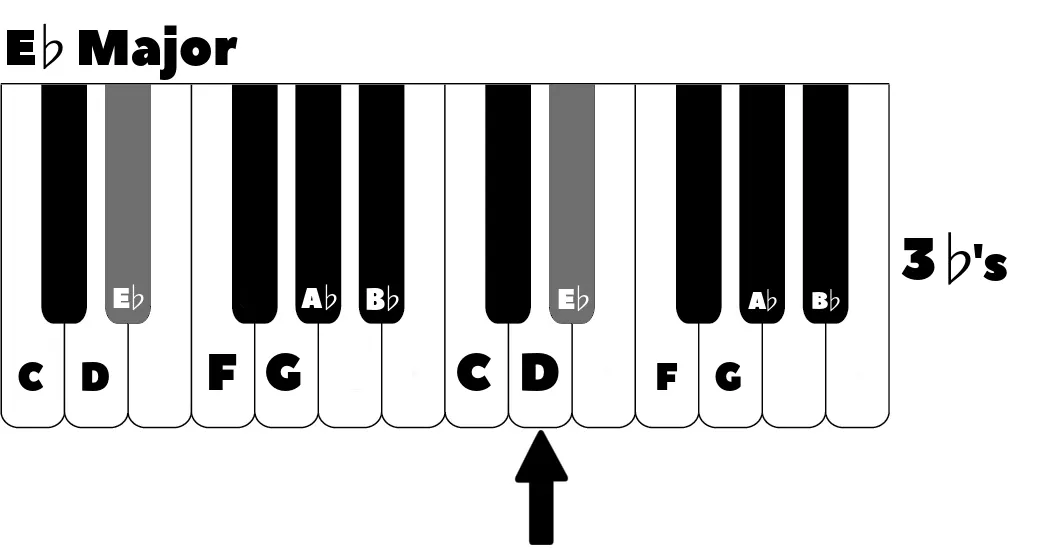

We’ve lost another flat! Our G♭ has been replaced by G. See the pattern? The process that creates sharps is the same process that eliminates flats! Let’s keep it rolling.

Welcome back! We’re at the beginning again.

Memorizing this whole thing is a feat. However, memorizing the process that makes this whole cycle happen is not difficult. Practice making each key by yourself. In just a few weeks, you’ll be able to maneuver all of the keys in order in less than 5 minutes. I’ve tucked a quick overview of this whole process into the end of this chapter.

Conclusion

The Circle is much more respectable when you realize that it is a representation of nature more than an exercise in mental vanity. The tones that humans around the world have grown to love are based on natural phenomena like the overtone series and directly imply this system. In fact, the first system of its kind was contained within Grammatika, a treatise that was written by composer and theorist Nikolai Diletski in the 1670’s before the fame of classical composers you hear about today like Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. Any music that is considered “tonal” is paying its respects to this system. An understanding of the Circle of Fifths is a gift that keeps on giving.

Keys are represented in written music in a specific way. The beginning of each piece or song includes a set of sharps or flats. For our purposes, all you really need to do is count how many of either there are and compare that to this circle of fifths chart. Are there four sharps at the beginning? You’re in the key of E major.

… Or you’re in the key of C# minor. More on this in Chapter 7: Modes.

KEY TIP: Some songs and pieces change keys in the middle, sometimes often and sometimes not. This is called modulation. Remember, a song is not necessarily bound by the key it is in.

Circle of Fifths Cheat Sheet

- Each key needs one instance of each letter A-G.

- Each key needs a leading tone, or a note that is one half step below the root.

- Begin in the key of C. It’s the simplest! No sharps or flats.

- Travel in fifths. Your next key is the fifth note of the key you just played.

- Add sharps as leading tones.

- When you get to the key of F#, play that key and then switch it to the key of Gb. Now you can continue.

- New leading tones will now eliminate flats one by one.

- Continue until you arrive back at the key of C.

Any questions? Ask in the comments! Thanks for reading, Steemit!