The first two paragraphs of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake take us on a tour of the master bedroom of the Mullingar House in Chapelizod, a village on the outskirts of Dublin, where the novel is set. There are seven stations in this memory palace. The opening paragraph comprises a single sentence (actually the second half of a single sentence), and each of the seven stations is alluded to by a word or phrase in that sentence. The second paragraph comprises seven separate clauses or sentences, one for each of the stations:

| Station | First Paragraph | Second Paragraph |

|---|---|---|

| Faucet | riverrun | Sir Tristram ... penisolate war |

| Basin | Eve | nor had topsawyer’s rocks ... all the time |

| Fireplace | Adam’s | nor avoice from afire ... thuartpeatrick |

| Door | swerve of shore | not yet, though venisoon after ... isaac |

| Window | bend of bay | not yet, though all’s fair in vanessy ... nathandjoe |

| Commode | commodious vicus of recirculation | Rot a peck ... arclight |

| HCE in Bed | Howth Castle & Environs | rory end ... on the aquaface |

What is particularly significant about this pattern is how clear it is: there is an obvious one-to-one relationship between the stations in the bedroom and the phrases or clauses that represent them on the page. This is because the elderly innkeeper—the novel’s only real character—has not yet fallen asleep. We can see these objects clearly as though the room is illuminated and we are still awake. We do not need to rely upon our ears, eyes of the darkness (RFW 012.09).

But the third paragraph changes all this. It opens with the words The fall, and it is at this moment, I believe, that the landlord falls asleep. It is precisely 11:32 pm on Saturday 12 April 1924. Like the first two paragraphs, the third paragraph also takes us on a tour of the bedroom, but the seven stations are no longer clearly illuminated. It is difficult to make them out, and two or three of them are now all but invisible.

The fall It is a bit of a stretch to see this as a reference to the faucet. Water does fall from a faucet, but, still ...

bababa The sound of water going down the plughole in the sink? Another long shot.

? The fireplace seems to have vanished. Perhaps the reference to Christy’s Minstrels, a name once shared by several black-and-white minstrel troupes in the 19th century, is meant to evoke the black faces of chimney sweeps, but this is another long shot.

well to the west The door is in the northwest wall of the bedroom, so this one makes sense.

at the knock out in the park Through the bedroom window, which is in the northeast wall, the Phoenix Park can be seen. So this too makes some sense.

oranges have been laid to rust upon the green The commode, which conceals a chamber pot, symbolizes death and decay. The phrase laid to rest and the word rust reinforce this theme of putrefaction. Later in the novel (RFW 088.01-09), the kitchen midden, or rubbish tip, in the backyard will be closely associated with oranges and orange peel.

devlins first loved livvy HCE and ALP in bed. devlins first can be glossed as Dublin’s Fürst (German: Fürst, prince). Note that the first two paragraphs ended with HCE in bed alone, whereas now he is joined by his wife ALP (Anna Livia Plurabelle = livvy). In the real world in 1924, the landlord is a seventy-year-old widower, so he is alone in bed. But in his dreams he is still a married man of thirty, with his wife at his side. This is further confirmation that he is still awake in the first two paragraphs, but has fallen asleep by the end of the third paragraph.

The Fall

The first two paragraphs of Finnegans Wake are primarily concerned with space and time. The opening sentence answers the question: Where are we? We are in a bedroom in Dublin. The second paragraph answers the question: When are we? We are back at the beginning of a story that has already been told many times before. The third paragraph answers the question: What is that story about? And it wastes no time in answering that question: Finnegans Wake is about the fall of man. We are also told the name of that man, the Everyman of our story: Finnegan.

The popular Irish-American ballad Finnegan’s Wake, from which Joyce took the name of his novel, recounts how a drunken Irish labourer, Tim Finnegan, while working on a building site in an American city, falls from a ladder and breaks his skull. Assumed dead, he is taken home to be waked. During the wake, a riot breaks out over who loved Tim the most. In the commotion, some whiskey splashes on Tim’s lips and he comes back to life. The word whiskey derives from the Irish name of this drink: uisce beatha, which means water of life.

Another popular faller is Humpty Dumpty, who is clearly alluded to in this paragraph. Perhaps the most famous depiction of this figure is in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1872). Carroll—both the man and his works—looms large over Finnegans Wake, though Joyce always claimed that he had never read him until people pointed out the similarities between the two writers after the publication of the first fragment from Work in Progress:

But the most obvious, and the most important, of Joyce’s verbal borrowing from Carroll is the portmanteau-word. Carroll’s invention of this is undisputed, and it is Humpty Dumpty ... who defined it first: “Slithy means lithe and slimy. Lithe is the same as active. You see it’s like a portmanteau—there are two meanings packed up into one word.” Joyce, however, was seldom content with just two meanings. In fact he seems to have aimed at packing as many meanings as possible into every single word. Humpty Dumpty himself, for example, is a symbol of the Fall of Man—he fell off a wall! He also signifies resurrection—an Easter egg! His name may be taken as meaning up and down ... This connects him with Vico’s cyclic theory of history. He is also one facet of H.C.E. He sometimes seems to be Finnegan. He is the cosmic egg of Egyptian mythology ... And in addition to all this he is the city of Dublin, and sometimes represents all Ireland. (Atherton 126)

Here, however, there is little more than a fleeting reference to the character in the nursery rhyme, so I will leave Lewis Carroll for another day.

Giambattista Vico

I have previously described how much of the underlying philosophy in Finnegans Wake was informed by the work of the 18th-century Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico. Curiously, in yet another of those serendipitous Wakean convergences, Vico once fell from a ladder and was left for dead, only to make a miraculous recovery. He has left us an account of this incident himself in his autobiography:

Giambattista Vico was born in Naples in the year 1670 [recte 1668] to honest parents of good repute. His father was of a sanguine humour, while his mother’s was quite melancholic: each contributed something to the character of their son. As a child, he was high-spirited and impatient of rest; but at the age of seven, he fell head first onto the ground from the top of a ladder, and remained motionless and unconscious for about five hours. The right side of his skull was fractured, though the skin was not broken. The fracture caused a large swelling. The boy lost so much blood as a result of the many deep lancings he required that the surgeon, observing the broken cranium and considering the duration of the coma, gave the following prognosis: that the boy would probably die, but if he survived, he would be an idiot for the balance of his life. But by the Grace of God neither part of his prediction came to pass. (Vico 1, my translation)

Thunder

While we are discussing Vico, we might as well deal with one of the best known and most notorious features of Finnegans Wake: the ten thunder words, the first of which makes its appearance in this paragraph:

“The fall”, and the strange polysyllable following it, introduce us to the propelling impulse of Finnegans Wake. The noise made by the thumping of Finnegan’s body tumbling down the ladder is identical with the Viconian thunderclap, the voice of God’s wrath, which terminates the old aeon and starts the cycle of history anew. (Campbell, Robinson & Epstein 29)

The rainbow, symbol of God’s grace, figured prominently in the first two paragraphs. Thunder, symbol of God’s wrath, is closely related to the rainbow, in the sense that both signify the end of one Viconian cycle and the beginning of the next. Joyce borrowed the rainbow from Genesis, but the thunderclap is Vico’s:

377 Of such natures must have been the first founders of gentile humanity when at last the sky fearfully rolled with thunder and flashed with lightning ... this occurred a hundred years after the Flood in Mesopotamia and two hundred after it throughout the rest of the world ... Thereupon a few giants, who must have been the most robust, and who were dispersed through the forests on the mountain heights where the strongest beasts have their dens, were frightened and astonished by the great effect whose cause they did not know, and raised their eyes and became aware of the sky. And because in such a case, as stated in the Axioms, the nature of the human mind leads it to attribute its own nature to the effect, and because in that state their nature was that of men all robust bodily strength, who expressed their very violent passions by shouting and grumbling, they pictured the sky to themselves as a great animated body, which in that aspect they called Jove, the first god of the so-called gentes maiores, who by the whistling of his bolts and the noise of his thunder was attempting to tell them something. And thus they began to exercise that natural curiosity which is the daughter of ignorance and the mother of knowledge, and which, opening the mind of man, gives birth to wonder ...

689 At length the sky broke forth in thunder, and Jove thus gave a beginning to the world of men by arousing in them the impulse which is proper to the liberty of the mind, just as from motion, which is proper to bodies as necessary agents, he began the world of nature ...

734 The natural theogony above set forth enables us to determine the successive epochs of the age of the gods, which correspond to certain first necessities or utilities of the human race, which everywhere had its beginnings in religion. The age of the gods must have lasted at least nine hundred years from the appearance of the various Joves among the gentile nations, which is to say from the time when the heavens began to thunder after the universal Flood ...

1097 Let us now conclude this work with Plato, who conceives a fourth kind of commonwealth in which good honest men would be supreme lords. This would be the true natural aristocracy. This commonwealth conceived by Plato was brought into being by providence from the first beginnings of the

nations. For it ordained that men of gigantic stature, stronger than the rest, who were to wander on the mountain heights as do the beasts of stronger natures, should, at the first thunderclaps after the universal Flood, take refuge in the caves of the mountains, subject themselves to a higher power which they imagined as Jove, and, all amazement as they were all pride and cruelty, humble themselves before a divinity. (Vico §377, §689, §734, §1097)

Vico invokes the thunder—especially the first thunder after the Universal Flood—about thirty times in his opus magnum, The New Science. The rainbow, however, does not interest him.

As Campbell & Robinson noted, Vico’s thunder is at once (1) the cause of man’s fall from a state of rude nature into civilization and (2) the sound-effect of that fall. It is the voice of Jove.

The first of Joyce’s hundred-letter thunderwords is not only an onomatopoeic representation of a thunderclap, it is also a babel of multilingual thunderbolts. Joyce concocted it from at least thirteen different words for thunder in thirteen different languages. The opening syllables—bababad—connect the word directly to the Tower of Babel and the Confusion of Tongues. They also sound like the word bad being spoken by someone with a stutter: b-b-bad. In Finnegans Wake, stuttering symbolizes sin and guilt. HCE regularly betrays his guilty conscience by stuttering. Joyce was happy to learn that Lewis Carroll stuttered—as did Charles Stewart Parnell, another important character in Finnegans Wake.

Osiris

As the landlord of the Mullingar House lies abed, his head is situated in the southeast of the bedroom, while his toes are pointing to the northwest. The image of the portly gentleman lying beneath the bedclothes in this particular orientation is an important one to which I will return in a future article. It will be especially significant from RFW 006.01 on. In Ulysses, Leopold Bloom adopts a peculiar orientation when he goes to sleep. He and Molly lie in bed in opposite directions:

In what directions did listener and narrator lie?

Listener, S. E. by E.; Narrator, N. W. by W.: on the 53rd parallel of latitude, N. and 6th meridian of longitude, W.: at an angle of 45° to the terrestrial equator. (Ulysses 870)

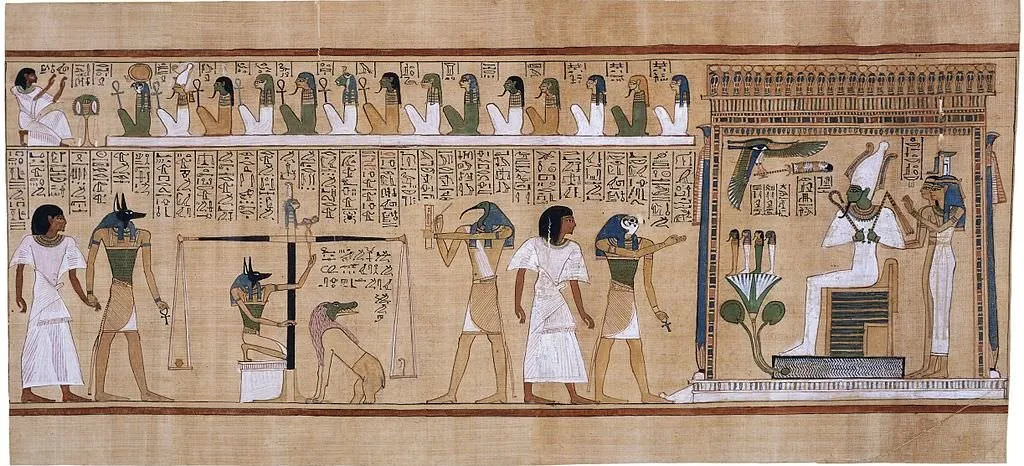

The quest for Finnegan’s toes reminds one of the story of the Egyptian god Osiris:

Osiris was a wise and beneficent king, who reclaimed the Egyptians from savagery, gave them laws and taught them handicrafts. The prosperous reign of Osiris was brought to a premature close by the machinations of his wicked brother Seth, who with seventy-two fellow-conspirators invited him to a banquet, induced him to enter a cunningly-wrought coffin made exactly to his measure, then shut down the lid and cast the chest into the Nile. Isis, the faithful wife of Osiris, set forth in search of her dead husband’s body, and after long and adventure-fraught wanderings, succeeded in recovering it and bringing it back to Egypt. Then while she was absent visiting her son Horus in the city of Buto, Seth once more gained possession of the corpse, cut it into fourteen pieces, and scattered them all over Egypt. But Isis collected the fragments, and wherever one was found, buried it with due honour; or, according to a different account, she joined the limbs together by virtue of her magical powers, and the slain Osiris, thus resurrected, henceforth reigned as king of the dead in the nether world. (Chisholm 50)

Osiris is an important character who turns up frequently in Finnegans Wake. It is fitting that both he and Lewis Carroll should appear together in this paragraph: Atherton was probably the first to note that references to Lewis Carroll in Finnegans Wake are frequently interwoven with references to Ancient Egypt (Atherton 132).

One of Osiris’s epithets, Wenen-nefer (The Ever Perfect One) gave rise to the names Onuphrius and Onofrio, which are sometimes Anglicized as Humphrey: HCE stands for Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker. Osiris is also known as The God at the Top of the Staircase (Budge xxv)—but he never fell down and broke his skull!

And it need hardly be pointed out that the Osiris-Isis-Seth triangle is yet another variant of the Shaun-Issy-Shem triangle in Finnegans Wake.

There may also be a reference here to an Irish genesis myth, The Slaying of the Mata, in which the dismembered body of a mythical beast gives rise to the Irish landscape—including, significantly, the ford of hurdles at Dublin, from which the city derived one of its names: Áth Cliath [Ford of Hurdles].

Áth Cliath: When the men of Erin broke the limbs of the Matae, the monster that was slain on the Liacc Benn [The Stone of Benn] in the Brug Maic ind Óc [Newgrange], they threw it limb by limb into the Boyne, and its shinbone (colptha) got to Inber Colptha (the estuary of the Boyne), whence Inber Colptha is said, and the hurdle of its frame (i.e. its breast [= ribcage?]) went along the sea coasting Ireland till it reached yon ford (¬áth); whence Áth Cliath is said. (Stokes 329)

According to Roland McHugh’s Annotations to Finnegans Wake, there is an allusion to the Mata in the final chapter of the book (FW 609.06 = RFW 476.18), which McHugh glosses thus:

Mata: 7-headed tortoise; offspring of Eve and the Serpent (McHugh 609)

No source is given for this. In Irish mythology the Mata is usually described as a giant sea-turtle with several heads (typically four), but I have not come across any source which identifies it as the offspring of Eve and the Serpent.

One Thousand and One Nights

There are ten thunderwords in Finnegans Wake. The first nine have 100 letters each : the last has 101 letters. The total, then, is 1001, which is undoubtedly a reference to the Thousand and One Nights. This is the title of a loose collection of Middle Eastern folktales. In the frame story of the collection, the tales are recounted at night by Shahrazad (or Scheherazade) to her sister Dunyazad, while the Sultan Shahryar listens spellbound. In Finnegans Wake Shahrazad and Dunyazad are the two personalities of schizophrenic Issy, and HCE is the Sultan, who overhears Issy talking to herself at night. Remember, Issy’s bedroom is above HCE’s and her voice is channelled to him down the chimney flue:

Shahrazad and Dunyazad: The sister heroines of the Arabian Thousand Nights and One Night, who regaled King Shahryar with their endless story cycle, and thus distracted him from his cruel design to ravish and slay a maid a night ... Their bedside tales correspond to ALP’s letter and Finnegans Wake itself. (Campbell, Robinson & Epstein 55 and fn)

The Salmon of Knowledge

The word oldparr obviously refers to Old Parr:

”Old Parr” was the nickname of Thomas Parr (1483-1635!), of Shropshire, who lived to be one hundred and fifty-two years old. (Campbell, Robinson & Epstein 29)

But parr is also the name for a stage in the life-cycle of the salmon:

- Alevin Newly hatched salmon

- Fry Young salmon

- Parr Juvenile salmon

- Smolt Adolescent salmon that are ready to go to sea

- Grilse Adult salmon that have returned to the fresh water to spawn after one year

Every schoolchild in Ireland has probably heard the story of Finn MacCool and the Salmon of Knowledge. It is one of the Boyhood Deeds of Finn mac Cumhail and tells how Finn came to acquire the wisdom of the famous Salmon:

Now it is to be told what happened to Finn at the house of Finegas the Bard. Finn ... went to learn wisdom and the art of poetry from Finegas, who dwelt by the River Boyne, near to where is now the village of Slane. It was a belief among the poets of Ireland that the place of the revealing of poetry is always by the margin of water. But Finegas had another reason for the place where he made his dwelling, for there was an old prophecy that whoever should first eat of the Salmon of Knowledge that lived in the River Boyne, should become the wisest of men. Now this salmon was called Finntan in ancient times and was one of the Immortals, and he might be eaten and yet live. But in the time of Finegas he was called the Salmon of the Pool of Fec, which is the place where the fair river broadens out into a great still pool, with green banks softly sloping upward from the clear brown water. Seven years was Finegas watching the pool, but not until after Finn had come to be his disciple was the salmon caught. Then Finegas gave it to Finn to cook, and bade him eat none of it. But when Finegas saw him coming with the fish, he knew that something had chanced to the lad, for he had been used to have the eye of a young man but now he had the eye of a sage. Finegas said, “Hast thou eaten of the salmon?”

“Nay,” said Finn, “but it burnt me as I turned it upon the spit and I put my thumb in my mouth.” And Finegas smote his hands together and was silent for a while. Then he said to the lad who stood by obediently, “Take the salmon and eat it, Finn, son of Cumhal, for to thee the prophecy is come. And now go hence, for I can teach thee no more, and blessing and victory be thine.” (Rolleston 113-114)

In later centuries, Finn was recast as an Irish giant, and it is in this guise that he figures most prominently in Finnegans Wake. We will be meeting him again.

First Draft

The first-draft version of this paragraph does not shed much light on the final version. There are, however, a few oddities about it that deserve mention:

The story of the fall is retailed early in bed and later in life throughout most christian minstrelsy. The fall of the wall at once entailed the fall of Finnigan, and the humpty hill himself promptly sends an inquiring one well to the west in quest of his tumptytumtoes. The upturnpikepoint is at the knock out in the park where there have been oranges on the green always & ever since the Devlin first loved liffey. (Hayman 46)

This first draft already incorporates a few second thoughts. After tumptytumtoes. Joyce began to write:

Two facts have come down to us

But he crossed this out and replaced it with:

Their resting

He was obviously going to write Their resting place, but he crossed out what he had written and immediately replaced it with the version given above.

What two facts did Joyce have in mind? Note also that it is the fall of a wall that causes Finnegan to fall, unlike Humpty Dumpty, who falls off a wall, while the wall remains standing. Finally, note how Joyce spells the name Finnigan. Is this a typo? Joyce wrote this draft in October 1926. Surely by then he had settled on Finnegan as the definitive spelling?

References

- James S Atherton, The Books at the Wake: A Study of the Literary Allusions in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale IL (1959, 2009)

- E A Wallis Budge, The Book of the Dead: An English Translation ... of the Theban Recension, Rutledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, London (1909)

- John Francis Campbell, The Celtic Dragon Myth, John Grant, Edinburgh (1911)

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, Edmund L Epstein (editor), A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, New World Library, Novato CA (2005)

- Hugh Chisholm (editor), Encyclopaedia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume 9, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1911)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin TX (1963)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, Ulysses, Penguin Books, London (1992)

- T W Rolleston, The High Deeds of Finn and other Bardic Romances of Ancient Ireland, Thomas Y Crowell Company, New York (1910)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Whitley Stokes, The Prose Tales in the Rennes Dindsenchas, Revue celtique, Tome XV, Librairie Émile Bouillon, Paris (1894)

- Giambattista Vico, L’Autobiografia, Giuseppe Laterza & Figli, Bari (1929)

Image Credits

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

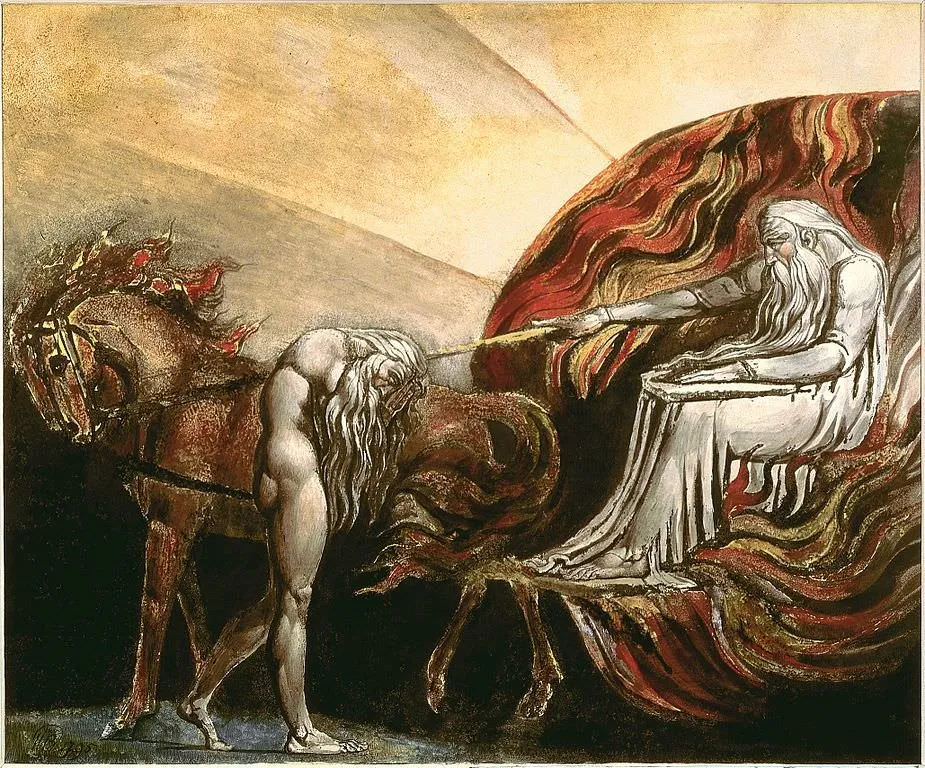

- God Judging Adam; Wikimedia Commons, William Blake (artist), Public Domain

- Giambattista Vico: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- The Confusion of Tongues: Wikimedia Commons, Gustave Doré (engraver), Public Domain

- The Judgment of the Dead in the Presence of Osiris: Wikimedia Commons, Book of the Dead of Hunefer, British Museum, Public Domain

- Scheherazade: Wikimedia Commons, Édouard Frédéric Wilhelm Richter (artist), Public Domain

- An Bradán Feasa (The Salmon of Knowledge): © Declan Killen, Fair Use

Video Credits

- Adam Harvey: DON’T PANIC: it’s only Finnegans Wake – thunderword #1, Standard YouTube License, Fair Use

Useful Resources