Researchers from Singapore, Germany, China and other countries have found that the body of embryos is able to suppress the immune response in response to foreign agents.

Despite the fact that the mother and embryo organisms are separated by the skin, there is a continuous exchange of nutrients between them. If the fetus has a developed immune system, the antigens coming from the amniotic fluid or blood should theoretically cause the corresponding reactions. However, in practice such an immune response does not occur. Clarification of the mechanism can help in the development of transplantation methods, the therapy of embryonic and multipotent stem cells, as well as gene therapy, to avoid a crisis of rejection. To fill the gap, the authors of the new work studied antigen-presenting cells of embryos and adults.

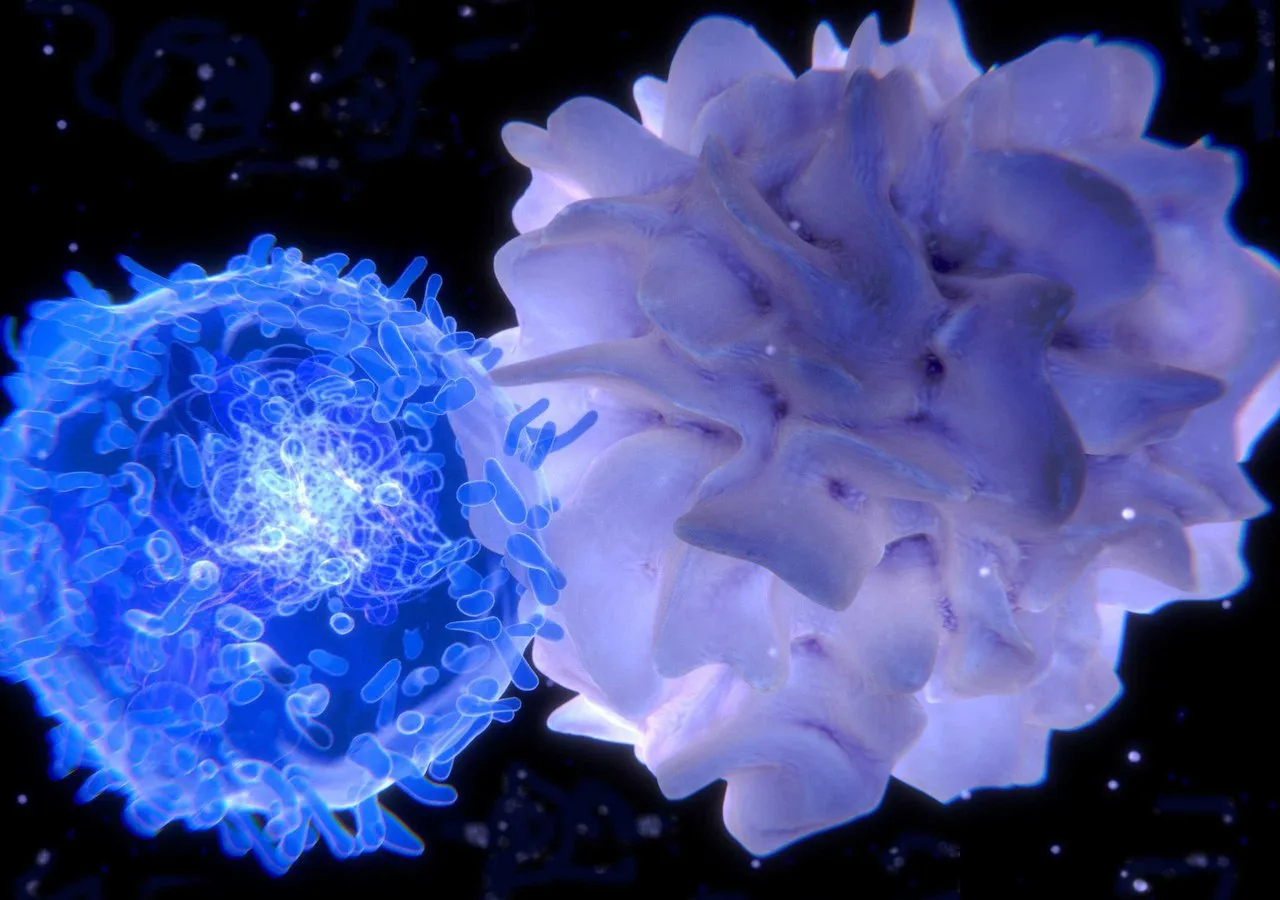

For a long time, the lack of an immune response was due to the primitive functioning of the immune system of embryos. In particular, the degree of development of dendritic cells remained unclear - along with B-lymphocytes and macrophages, they capture the antigen by endocytosis or phagocytosis, after which they represent a fragment of the agent located on the membrane, T-lymphocytes. With successful recognition, the latter trigger an immune response, destroying similar antigens and damaged cells of their own organism. The results of the analysis showed that, contrary to the dominant hypothesis, dendritic and T-cells of embryos are capable of an immune response already at the 13th week of pregnancy.

So, according to experiments, the immunity of the fetus, like that of adults, can capture foreign agents and represent their fragments to T lymphocytes. However, after that, their body activates regulatory T cells - they modulate the response power through effector lymphocytes. At the molecular level, such an adjustment, in the case of dendritic cells, is mediated by the production of the enzyme arginase-2, which by suppressing the level of L-arginine suppresses production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Curiously, the excess of this protein positively correlates with miscarriages. Nevertheless, the expression of over three thousand genes of dendritic cells in infants and embryos is different.

In addition to the potential for transplantation and gene therapy, clarifying the mechanism for suppressing the immune response in the fetus can help in studies aimed at minimizing the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. According to statistics, excessive immune reactions of embryos lead to miscarriages in 40 percent of cases. It is suggested that, for example, intrauterine infections may increase the likelihood of response. To clarify this mechanism, as well as to suggest ways of preventing such undesirable reactions, the authors intend to further study. Previously, risk factors for pregnancy included passive smoking before conception, listeriosis and diet.

The article was published in the journal Nature.