I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the twenty-eighth installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5 | Ch 6 | Ch 7 | Ch 8 | Ch 9 | Ch 10 | Ch 11 | Ch 12 | Ch 13 | Ch 14 | Ch 15 | Ch 16 | Ch 17 | Ch 18 | Ch 19 | Ch 20 | Ch 21 | Ch 22 | Ch 23 | Ch 24 | Ch 25 | Ch 26] and every few days I'll post another chapter. From the back cover:

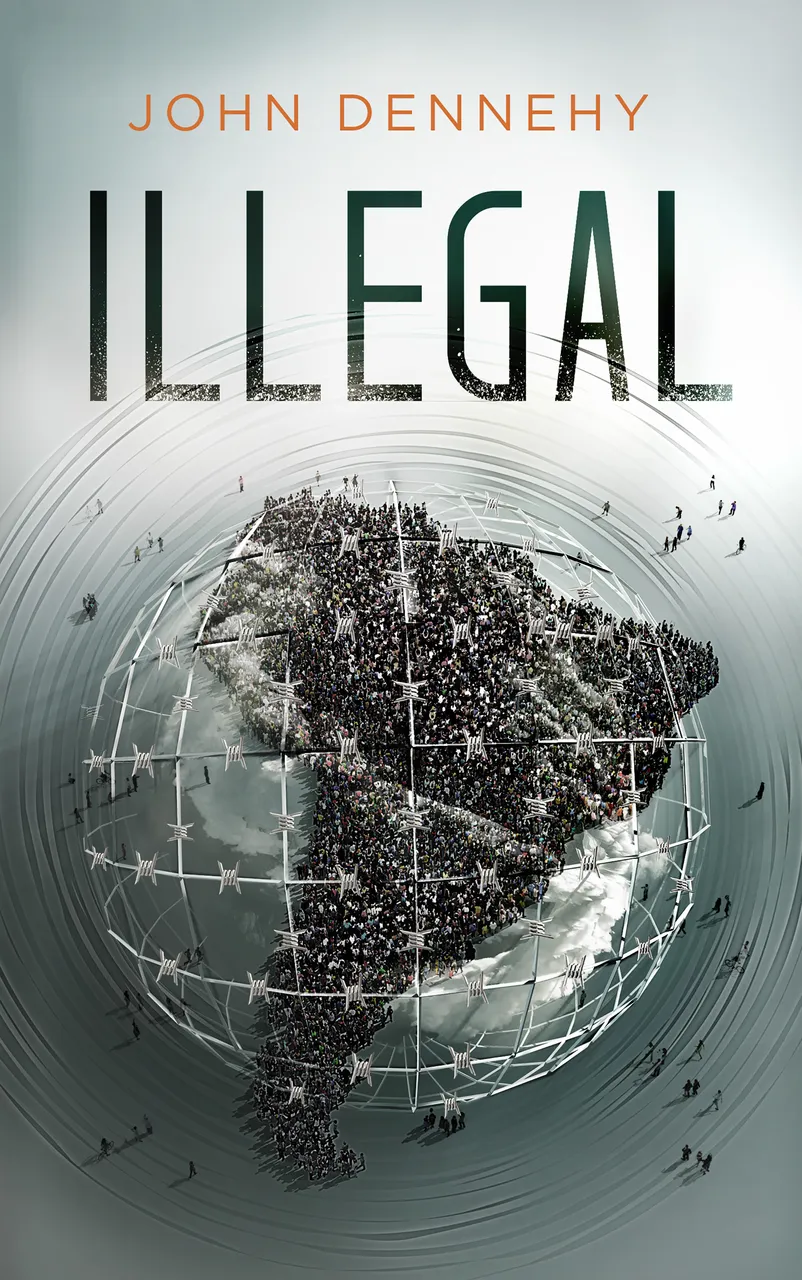

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

--

Crossing Four March 29, 2007

Giving Up on Hope [Chapter Twenty-Eight]

I could argue that I got deported at a bad time, but there’s no good time to be forced to leave your home. Everyone who is deported is already dealing with a myriad of other issues, just like any other person. Whatever problems I had before became magnified, and much of what made me happy drifted deeper into the cracks.

A few weeks after I got back from my January crossing, there was one particularly disturbing incident. I had just returned to the downtown apartment Lucía and I were renting when I heard the doorbell and the loud screech of tires. By the time I reached the door there was no one outside and no cars in sight, but there was a shoebox on the step. The shoebox was crushed, with a tire mark across it. A bright red liquid oozed out of the torn cardboard sides. Curious, I opened the box: inside was a dead and badly disfigured guinea pig. It looked like they had run over the box while the animal was trapped inside, still alive. Blood had splattered on the sides of the box and the animal’s intestines poked through the torn skin and fur. The front lip was peeled back and ripped from its face, revealing a handful of broken teeth and slashed gums.

I wanted to vomit and cry at the same time. I felt horrible, and a dozen paranoid thoughts raced through my mind. Is this because I’m American? Is it someone I know? Do they know that guinea pigs are pets in my country? Did they know I was home? Are they watching me? Did the same people leave the dog shit on the step yesterday? Will they come back?

The anti-American sentiments I had dealt with before had been annoying though bearable—but the mutilated guinea pig was the breaking point. After I went back inside and collected myself, I fell into a state of depression and waited for Lucía to come home. But when I told her what had happened, she didn’t seem to care. She didn’t understand why I was so upset.

“I live here, that’s why. This is my home,” I shouted at her. “People spit on me in the park and leave dead animals at our door and you don’t even care.” And for the first time I started to seriously think that maybe this wasn’t my home, that maybe Lucía wasn’t the woman for me, that maybe the dream was just fantasy.

That same week, while I still clung to the idea that things would work out with Lucía and me, with Ecuador and me, I walked past a protest in the park. A hundred youths, faces covered with bandanas, were blocking the road while a group of riot police lined up a block away. The police were putting on their gas masks; the protesters were collecting pieces of pavement and rocks for a counterattack. After I passed the protesters and had my back to them, I heard one yell after me.

“¡Fuera Yankee!—Yankee go home.”

I turned around and looked in the direction the voice came from.

He said it again. It was the tall one with the red bandana. I turned and walked straight for him. A crowd gathered to watch what would happen.

“What did you say?” I asked.

“Yankee go home,” he repeated, though with less confidence in his voice.

I laughed but did not smile, did not break eye contact. “You don’t like my country because it treats Ecuador unfairly. Because it doesn’t know your nation but it makes assumptions about it. Because it thinks all of Latin America is the same, thinks all Ecuadorians are the same. Because it thinks it knows you, but it’s ignorant.” I paused. “You’re the same. I live here. I work here. And the U.S. government does not represent me anymore than Lucio represented you. You’re the same as the U.S; you’re part of the problem.”

The man with the red bandana responded in a voice so low that I barely heard him above the noise of the protest, “I’m sorry. I didn’t know.”

I turned my back and walked away. At the time I felt proud, but what if the roles were reversed? What if the protest was in the United States and had anti-immigrant undertones? What if one of the protesters shouted at an Ecuadorian walking by or a Muslim woman in a hijab and that person confronted the crowd?