Un mundo que solo valore lo "práctico" se vería privado de la capacidad de análisis crítico, la innovación y la comprensión de las complejidades del ser humano y la sociedad.

Saludos humanistas a toda la comunidad. Esta es mi participación en la iniciativa Las Humanidades: ¿Están en crisis o son una opción educativa? En la que tomaré como eje central la relación entre la ciencia y la filosofía.

Invito a participar en esta iniciativa a todos los amigos/as de las humanidades.

Enlace

Enlace

A world that only values the "practical" would be deprived of the ability of critical analysis, innovation, and understanding of the complexities of human beings and society.

Greetings humanists to the whole community. This is my participation in the initiative Humanities: Are they in crisis or are they an educational option? In which I will take as the central axis the relationship between science and philosophy.

I invite all friends of the humanities to participate in this initiative.

Link

Link

El “hacer” bien las cosas es siempre lo más fácil. Una de las plagas de la vida moderna es, en efecto, la muchedumbre de incapaces o de bárbaros que dominan las técnicas y adquieren por ello una peligrosa responsabilidad social. […] Lo difícil, lo importante, no es ejecutar las técnicas, sino saber plantear los problemas que haya detrás y juzgarlos con espíritu científico, que sólo se adquiere con cultura.

Gregorio Marañón. La medicina de Nuestro Tiempo. 1954

Presentación

En este micro-ensayo sobre la relación entre ciencia y filosofía tomaré como inicio lo que no es la ciencia.

"The 'doing' things right is always the easiest. One of the plagues of modern life is indeed the crowd of the incapable or barbarians who master the techniques and acquire thereby a dangerous social responsibility. […] The difficult, the important thing, is not to execute the techniques, but to know how to pose the problems behind them and to judge them with scientific spirit, which is only acquired through culture.

Gregorio Marañón. The Medicine of Our Time. 1954

Introduction

In this micro-essay on the relationship between science and philosophy, I will start by what is not science.

La ciencia no es un monolito

La ciencia es una obra colectiva que se desarrolla y avanza de forma no lineal, en la cual las nuevas ideas chocan con las pasadas y se imponen no sin dificultades. Escribía Ortega y Gasset, algo así como, que hasta el sabio más sabio prefiere creer en su error antes que en la verdad de otros. Un buen ejemplo de este fenómeno, es el recorrido de la Teoría General de la Relatividad (TGR) durante las dos primeras décadas de su formulación.

Uno de los personajes más populares de la historia es un científico, Albert Einstein. Transcurrido un siglo desde la publicación, en 1915, de la Teoría General de la Relatividad, su imagen se mantiene como un icono pop, junto a otros como Marilyn o Van Morrison.

Siendo esto cierto, quizás nunca te hayas preguntado por qué Einstein no recibió el premio Nobel por la Teoría Geneal de la Relatividad. De hecho, fue galardonado con el Nobel en 1922, por otro motivo, por las investigaciones que confirmaban la naturaleza cuántica de la luz y la dualidad onda-partícula.

Science is not a monolith

Science is a collective work that develops and advances in a non-linear manner, in which new ideas collide with the past and impose themselves not without difficulties. Ortega y Gasset wrote, something like, that even the wisest sage prefers to believe in their error rather than in the truth of others. A good example of this phenomenon is the journey of the General Theory of Relativity (GRT) during the first two decades of its formulation.

One of the most popular figures in history is a scientist, Albert Einstein. A century after its publication in 1915,of the General Theory of Relativity his image remains an iconic figure, alongside others like Marilyn or Van Morrison.

This being true, you may never have wondered why Einstein did not receive the Nobel Prize for the Geneal Theory of Relativity. In fact, he was awarded the Nobel in 1922, for another reason, for research confirming the quantum nature of light and wave-particle duality.

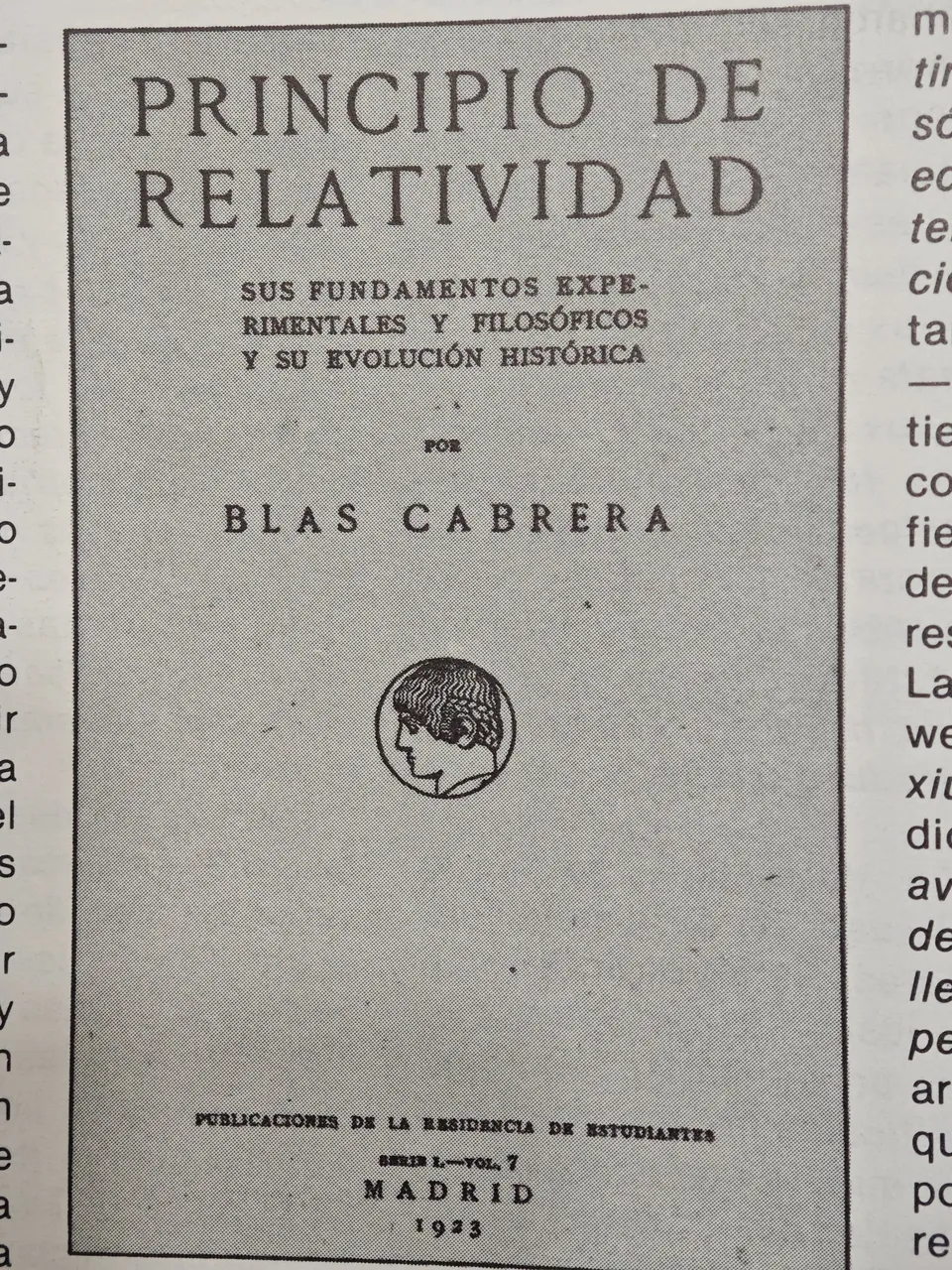

Una Historia de la Teoría General de la Relatividad

Tal vez pueda parecer sorprendente, pero la TGR en los años 30 del siglo XX era una teoría en retirada. Así lo refleja, uno de los colaboradores y amigo de Einstein, B. Hoffmann (1972):

En 1936 [Einstein] recibió un duro golpe. Tras larga y penosa enfermedad había muerto Marcel Grossmann, sin cuya fiel amistad quizá no hubiera florecido nunca el genio de Einstein. Se estaban rompiendo los lazos con el pasado. Además, hacía tiempo que había desaparecido el interés inicial por la teoría general de la relatividad. Entre los físicos era una teoría en retirada. Sin embargo. Einstein siguió trabajando.

En 1922 el matemático francés Paul Painlevé puso de relieve en “Le Petit Pariesien”, tanto la división de los científicos con respecto a la TGR, como la duda sobre el recorrido de la teoría:

Entre los sabios, unos claman al milagro, otros a la ilusión. Los fundamentos de la nueva doctrina, ¿serán indestructibles, o serán profundamente modificados, o incluso, no se tratará tan sólo de una fase creadora de la ciencia moderna cuyos resultados terminarán en los marcos clásicos? Un futuro próximo lo dirá.

Ese mismo año, Einstein es invitado por la Academia de Ciencias de Francia a participar en una sesión. No acude a la cita, al descubrir que la mayor parte de los miembros de la Academia habían decidido abandonar la sala con su llegada como protesta en contra de la TGR.

En Alemania, Lenard, Premio Nobel en 1905, pasa a ser uno de los mayores opositores de la teoría de la TGR.

Entre 1920 y 1922, Emile Picard, secretario de la Academia de la Ciencia de Francia, y Paul Painlevé, miembro de la Academia y presidente del Consejo durante la guerra, mostraron sus dudas sobre el valor de la TGR.

En 1921, el magnate Henty Ford publica en un semanario de su propiedad, Dearborn Independent, que Einstein ha plagiado:

¿Es Einstein un plagiador?- Escribía H. Ford de forma acusatoria.

Eduard Guillaume, físico y matemático suizo, anunció en 1922 el propósito de “demoler la teoría de Einstein”.

En diciembre de 1919, la Royal Astronomical Society decidió conceder a Einstein su medalla de oro de 1920. Sin embargo, la oposición de una gran parte de los miembros de la Sociedad postergó la entrega de esta medalla hasta 1926.

A General Relativity Theory Story

I t may seem surprising, but in the 1930s, General Relativity Theory (GRT) was a theory in decline. This was reflected by one of Einstein's collaborators and friends, B. Hoffmann (1972):

In 1936, [Einstein] suffered a hard blow. After a long and painful illness, Marcel Grossmann passed away, whose loyal friendship may have been crucial for Einstein's genius to flourish. The ties to the past were breaking. Moreover, the initial interest in general relativity theory had long since faded among physicists. However, Einstein continued working.

In 1922, the French mathematician Paul Painlevé highlighted in "Le Petit Parisien" both the division among scientists regarding GRT and doubts about the course of the theory:

Among the wise, some cry out for miracles, others for illusions. Will the foundations of the new doctrine be indestructible, deeply modified, or perhaps only represent a creative phase in modern science whose results will fit within classical frameworks? The near future will tell.

That same year, Einstein was invited by the French Academy of Sciences to participate in a session. He did not attend the meeting after finding out that most members of the Academy had decided to leave the room upon his arrival as a protest against GRT.

In Germany, Lenard, Nobel Prize winner in 1905, became one of the main opponents of the GRT.

Between 1920 and 1922, Emile Picard, Secretary of the Academy of Sciences in France, and Paul Painlevé, a member of the Academy and president of the Council during the war, expressed their doubts about the value of GRT.

In 1921, tycoon Henty Ford publishes in a weekly newspaper he owns, Dearborn Independent, that Einstein has plagiarized:

Is Einstein a plagiarist?- wrote H. Ford accusingly.

Eduard Guillaume, a Swiss physicist and mathematician, announced in 1922 his intention to "demolish Einstein's theory".

In December 1919, the Royal Astronomical Society decided to award Einstein its 1920 gold medal. However, opposition from a large part of the Society's members delayed the awarding of this medal until 1926.

Los hechos tangibles

En esos años, la TGR chocaba con dos fuerzas opuestas, la tradición y el empirismo.

Henri Bouasse (1866-1953), es un ejemplo de ésto, siendo un feroz partidario de los hechos tangibles frente a las "intuiciones" de Einstein. También será un radical defensor de la física de Newton. H. Bouasse juzgaba que todo descubrimiento en el campo de la física debía de encajar en el mundo de Newton para considerarse científico.

Entre los años 1923 y 1939, escribirá Ortega y Gasset “Meditación Sobre la Técnica” y entre sus capítulos se encuentra uno dedicado a la “bronca en la física” (1937). Meditación que recoge el desacuerdo y la “bronca” entre las dos escuelas que durante unas tres décadas compitieron por la hegemonía en el mundo de la física.

Explica Ortega que la física moderna, la de Einstein, se parece cada vez más a la geometría, el experimento y la observación del objeto a estudiar no existen, han desaparecido:

… lo que es más sorprende aún, se obtienen por simple inferencia de la lógica matemática , nuevas leyes. El experimento, la inducción, no aparecen en forma alguna.

Las propias palabras de Einstein, pronunciadas durante la celebración oficial del sesenta cumpleaños de Planck, aclaran todavía más el nuevo rumbo que había tomado la física en el siglo XX:

La tarea suprema del físico es llegar a unas leyes universales y elementales a partir de las cuales se pueda construir el cosmos por pura deducción. No hay un sistema lógico para llegar a esta leyes; sólo la intuición, basada en una inteligencia comprensiva, nos permite acercarnos a ella…

Volviendo al texto de Ortega, la otra escuela que compite con la “intuición” en la ciencia es el empirismo. Esta otra forma de entender la ciencia, aparece perfectamente recogida en el ensayo de Ortega mediante el testimonio de un periodista escandalizado por el nuevo curso de la física:

El primer paso en el estudio de la naturaleza debe ser la observación y no deben admitirse principios generales que no sean derivados de la inducción a que se somete la observación.

Es decir, para los empiristas, la ciencia no puede inferir nada más allá de lo que percibimos, de nuestras sensaciones.

Visible Facts

In those years, the GRT clashed with two opposing forces, tradition and the empiricism.

Henri Bouasse (1866-1953) is an example of this, being a fierce supporter of tangible facts over Einstein's "intuitions". He will also be a radical defender of Newtonian physics. H. Bouasse is of the opinion that every discovery in the field of physics must fit into Newton's world to be considered scientific.

Between the years 1923 and 1939, Ortega y Gasset will write "Meditation on Technology" and among its chapters is one dedicated to the "argument in physics" (1937). The meditation captures the disagreement and "argument" between the two schools that competed for dominance in the world of physics for three decades.

Ortega explains that modern physics, Einstein's physics, is increasingly resembling geometry, experiments and observations of the object under study do not exist, they have disappeared:

… what is even more surprising, are obtained by simple inference of mathematical logic, new laws. Experiment, induction, do not appear in any form.

Einstein's own words, spoken at the official celebration of Planck's sixtieth birthday, further clarify the new direction physics had taken in the twentieth century:

The supreme task of the physicist is to arrive at universal and elementary laws from which the cosmos can be built by pure deduction. There is no logical system to arrive at these laws; only intuition, based on comprehensive intelligence, allows us to approach them...

Returning to Ortega's text, the other school that competes with "intuition ” in science is empiricism. This other way of understanding science, is perfectly reflected in Ortega's essay through the testimony of a journalist scandalized by the new course of physics:

The first step in the study of nature must be observation, and no general principles that are not derived from the induction to which observation is subjected should be admitted.

Therefore, for empiricists, science cannot infer anything beyond what we perceive, from our sensations.

La polémica entre Einstein y Mach

Como los caminos de la divulgación científica son inescrutables, hemos llagado al siglo XXI con la agria polémica entre Einstein y Mach, desaparecida en el limbo de la historia. El tema a debate no fue otro que los límites de la ciencia. Si la ciencia es observación o es algo más.

Ernst Mach, físico y filósofo, fue una de las grandes influencias de Einstein en su juventud hasta que chocaron sus dos formas de ver el mundo. Einstein, partiendo de las ideas de Mach terminará por enfrentarse, e incluso mofarse, de su maestro.

Mach como filósofo se encuentra entre los empiristas. ¿Cuáles son alguno de los principios básicos del empirismo de Mach?

El origen de todo conocimiento verdadero se encuentra en nuestras sensaciones.

Las entidades no observables, como el “átomo” a principios del s XX, pertenecen al campo de las conjeturas y no de la ciencia.

Inferir una realidad más allá de nuestras sensaciones como hace la TGR no pertenece al campo de la ciencia, sino de la especulación.

Las “intuiciones” de Einstein se encuentran fuera del campo de la ciencia.

The controversy between Einstein and Mach

As the paths of scientific dissemination are inscrutable, we have reached the 21st century with the bitter controversy between Einstein and Mach missing in limbo of history. The topic under debate was none other than the limits of science. Whether science is observation or something more.

Ernst Mach, physicist and philosopher, was one of the great influences on Einstein in his youth until their two ways of seeing the world clashed. Einstein, starting from Mach's ideas, would eventually confront, and even mock, his teacher.

Mach as a philosopher stands among the empiricists. What are some of the basic principles of Mach's empiricism?

The origin of all true knowledge lies in our sensations.

Unobservable entities, like the "atom" at the beginning of the 20th century, belong to the realm of conjecture, not science.

Inferring a reality beyond our sensations as done in the TGR does not belong to the realm of science but of speculation.

Einstein's "intuitions" fall outside the realm of science.

Primero fue la filosofía

No tengo mejor expresión que la de "religiosa" para definir esta confianza en la naturaleza racional de la realidad y en el hecho de esta sea accesible, en cierta medida, a la razón humana. Cuando falta este sentimiento, la ciencia degenera en un empirismo absurdo.

Einstein a Maurice Solvine (1951)

Hasta ahora he tratado de mostrar que no hay una concepción única de ciencia. Que incluso en una ciencia “dura”, como la física pueden convivir varias escuelas, es decir, la “ciencia” no es un monolito. A cada concepción de lo que es ciencia, le precede una escuela de filosofía. Por tanto, primero es la filosofía y después le sigue la ciencia.

La filosofía no sólo determina el desarrollo de la ciencia, también determina si la ciencia como empresa es una actividad factible. La actividad científica parte de una respuesta afirmativa a preguntas fundamentales que sólo desde la filosofía se pueden contestar.

La existencia de la ciencia, como la entiende Einstein, parte de previos no demostrables. Uno de ellos es que existe una realidad independiente de nosotros:

Que lo que percibimos, nuestras sensaciones, no sea un fruto de nuestra imaginación, un producto de nuestra mente.

Que esa realidad exterior, regida por leyes, se pueda conocer.

Y en este debate anda la filosofía desde hace siglos. Hume, desde su empirismo radical, niega la posibilidad de conocimiento alguno:

Siempre que pensemos que nuestras percepciones y los objetos son lo mismo, nunca podremos inferir la existencia de uno del otro, ni argumentar a partir de la relación causa-efecto; que es lo único que puede darnos certeza sobre los hechos.

Tratado sobre la Naturaleza humana (1738–40)

First came philosophy

I have no better expression than “religious” to define this confidence in the rational nature of reality and in the fact that it is accessible, to a certain extent, to human reason. When this feeling is lacking, science degenerates into an absurd empiricism.

Einstein to Maurice Solvine (1951)

So far I have tried to show that there is no single conception of science. That even in a "hard" science, like physics, several schools can coexist, that is, "science" is not a monolith. Each conception of what is science is preceded by a school of philosophy. Therefore, philosophy comes first and then science follows.

Philosophy not only determines the development of science, it also determines if science as an enterprise is a feasible activity. Scientific activity starts with an affirmative response to fundamental questions that can only be answered through philosophy.

The existence of science, as understood by Einstein, is based on unprovable assumptions. One of them is that there is a reality independent of us:

That what we perceive, our sensations, is not a product of our imagination, a creation of our mind.

That this external reality, governed by laws, can be known.

And philosophy has been debating this for centuries. Hume, with his radical empiricism, denies the possibility of any knowledge:

Whenever we think that our perceptions and objects are the same, we can never infer the existence of one from the other, nor argue from the cause-effect relationship; which is the only thing that can give us certainty about facts.

A Treatise of Human Nature (1738–40)

El pragmatismo

Cada periodo está gobernado por un talante, con el resultado de que la mayoría de los hombres son incapaces de ver el tirano que los gobierna.

Einstein a Maurice Solvine (1938)

Llegados aquí, debería ser obvia la importancia de la filosofía, y por extensión de las humanidades. Sin embargo las humanidades, no es que estén en crisis, están siendo desplazadas por una escuela de filosofía que es el pragmatismo.

Para el pragmático algo es verdad si funciona. Lo que "funciona" es “verdad”. ¿Quién puede negar esta verdad? Pues… el que escribe no sólo la niega… sino que piensa que es una idiotez (propia de los tiempos que vivimos).

Veamos. Dejar a un niño pequeño delante de la pantalla de un móvil para que no moleste puede que fucione y que el niño deje de molestar, pero no es lo mejor para el niño.

Beber una copa de licor puede funcionar para combatir la ansiedad, pero nadie puede negar que que no es el mejor tratamiento para la ansiedad. Y, desde luego, nadie forzaría la “verdad” llegando a afirmar que un desequilibrio en la cantidad de alcohol en sangre es la causa de la ansiedad.

En el campo de la salud la perversión del pragmatismo debería ser evidente. De tal forma, que mientras la salud depende de muchos factores como la alimentación, la vivienda, el trabajo digno, la educación, la calidad del aire que respiramos, la calidad del agua que bebemos, de nuestras redes sociales, el acceso a la cultura, etc. La "ciencia" ha encontrado su “verdad” en el “fármaco”, en el negocio.

En el campo de lo social, el pragmatismo, se ha convertido en la filosofía del nuevo autoritarismo protagonizado por los “expertos”. Técnicos y burócratas que en nombre de una nueva religión, llamada “ciencia”, dictan lo que es útil ¿para quién? y lo que no lo es. Una burocracia que, escondida tras palabras vacías como ciencia, plan de desarrollo, progreso…, impulsa procesos como los de gentrificación o envenena los acuíferos con pesticidas.

En mi campo, la psicología, el daño parece irreparable, los planes de estudio cada vez son más “científicos” y menos humanistas.

Vivimos malos tiempos para las humanidades y, más en concreto, para la filosofía. Es una actividad “inútil” en un mundo donde domina lo “útil”.

El “progreso” parece que no es posible sin un ingrediente fundamental: la obediencia ciega y la docilidad. Por tanto, no espero otra cosa que el pragmatismo continúe su labor de demoler todo pensamiento crítico y por extensión, toda filosofía no pragmática.

Final

Este micro-ensayo ha sido posible gracias al Heráclito que llevo dentro, que me lleva a estudiar la historia de la ciencia a través de sus hechos y no de sus mitos. También agradezco la colaboración del Diógenes que me acompaña que, iluminando mi camino entre las tinieblas que pueblan la Tierra, me hace innecesarias las reverencias para seguir volando.

Primero fue la filosofía.

Si has llegado hasta aquí gracias y enhorabuena por tu perseverancia.

Pragmatism

Each period is governed by a mood, with the result that most men are unable to see the tyrant who rules them.

Einstein to Maurice Solvine (1938)

At this point, the importance of philosophy, and by extension the humanities, should be obvious. However, the humanities are not in crisis, they are being displaced by a school of philosophy which is pragmatism.

For pragmatic something is true if it works. What “works” is “truth”. Who can deny this truth? Well... the writer not only denies it... but thinks it is idiotic (typical of the times we live in).

Let's see. Leaving a small child in front of the screen of a cell phone so that it does not disturb may work and the child stops disturbing, but it is not the best thing for the child.

Drinking a glass of liquor may work to combat anxiety, but no one can deny that it is not the best treatment for anxiety. And, of course, no one would force the “truth” by claiming that an imbalance in the amount of alcohol in the blood is the cause of anxiety.

In the field of health, the perversion of pragmatism should be evident. In such a way, while health depends on many factors such as nutrition, housing, dignified work, education, the quality of the air we breathe, the quality of the water we drink, our social networks, access to culture, etc., "science" has found its "truth" in the "drug," in business.

In the social sphere, pragmatism has become the philosophy of the new authoritarianism led by "experts." Technicians and bureaucrats who, in the name of a new religion called "science," dictate what is useful for whom and what is not. A bureaucracy that, hidden behind empty words like science, development plan, progress..., drives processes like gentrification, or poisons aquifers with pesticides.

In my field, psychology, the damage seems irreparable, study plans are becoming increasingly "scientific" and less humanistic.

We are living in difficult times for the humanities and, more specifically, for philosophy. It is an "useless" activity in a world where "useful" reigns. oes not seem to be possible without a fundamental ingredient: blind obedience and docility. Therefore, I expect nothing but pragmatism to continue its work of demolishing all critical thinking and, by extension, all non-pragmatic philosophy.

Final

This micro-essay has been made possible thanks to the Heraclitus within me, which leads me to study the history of science through its facts and not its myths. I am also grateful for the collaboration of Thanks to the Diogenes that accompanies me, who illuminates my path through the darkness that populates the Earth, making it unnecessary for me to bend down to continue flying.

First there was philosophy.

If you have made it this far, thank you and congratulations for your perseverance.

Banner edited with Canva pro y recortado con ezgif.com.

Banner edited with Canva pro and cropped with ezgif.com.

Avatar creado con IA Ideogram.

Avatar created with IA Ideogram.

Translated and formatted with Hive Translator by @noakmilo.

Todas las fotografías son de mi propiedad tomadas de una revista y un libro de mi propiedad, con mi teléfono Xiaomi 14.

All photographs are my property taken from a magazine and a book of my property, With my Xiaomi 14 phone.

Todas las imágenes creadas con IA Ideogram.

All images created with IA Ideogram.