The calculating machine, the brain without a soul, a dehumanized thinker… All things that Sherlock Holmes is not. It is precisely one of its secrets that he would sometimes or often display strong emotions, in contrast with his more professionally usual coldness and his introverted personality, but these two things did not stop him, however, from being actually a quite kind person in his manners and speech, while hardly ever displaying what you might say "warmness". Usually, only with Watson he’d show his warm side; and when police inspectors were being quite incompetent he would let loose his ability for offensive sarcasm and irony, but not even after Lestrade taunted him quite disrespectfully when he thought he had won one over him in The Norwood Builder did Sherlock remain with resentment afterwards, though he did enjoy letting him in the dark for a moment after he solved the case.

One thing to notice, however, is that it is Dr. Watson who sometimes refers to Sherlock as the things I listed earlier or similar ones, but Watson is himself quite an emotional fellow, and also of more normal human relationships than Holmes’, while not someone with many friends either, but it is partly from comparing Sherlock to himself that Watson arrives at calling him those things.

Holmes, indeed, intends to keep emotions down to a minimum so that they don’t get in the way of his reasoning, as it is cold reason the thing he values the most, but this is mainly so during the cases; several times, at the end of one, he would launch a more emotional remark about something of the case. And he certainly believes in good and evil, and his acceptance for breaking the law if necessary to solve a case is not derived as much from his desire to solve the case or fulfil his duty to his client as much as it is for serving the cause of justice when he believes that it is beyond the law to achieve that (Watson too). For example, two times he illegally breaks into houses of blackmailers to take the documents with which the blackmailing is based on, and a couple more times as well for different purposes.

Also, he is not an atheist, of which the greatest example of that is his rose talk in The Naval Treaty:

What a lovely thing a rose is! There is nothing in which deduction is so necessary as in religion. It can be built up as an exact science by the reasoner. Our highest assurance of the goodness of Providence seems to me to rest in the flowers. All other things, our powers, our desires, our food, are all really necessary for our existence in the first instance. But this rose is an extra. Its smell and its colour are an embellishment of life, not a condition of it. It is only goodness which gives extras, and so I say again that we have much to hope from the flowers.

Now, what I’ve said this far is about Sherlock Holmes’ personality, and it is his personality what it is of the utmost importance, even more than his detective skills, for it is that he is a most interesting person what propels him above other similar detective characters, such as C. Auguste Dupin. Dupin, the creation of Edgar Allan Poe, is closer than Sherlock to being a calculating machine (although it is fair to notice that he only appears in three short stories); so, despite Dupin having appeared earlier, and almost (if not entirely) created the detective genre as it is mostly known, he is less relatable than Holmes to the reader.

A very interesting take on the creation of Sherlock Holmes and the relationship of Conan Doyle with his creation is in the movie of 2005 The Strange Case of Sherlock Holmes & Arthur Conan Doyle.

By no means, however, have I intended to overlook the detective part of Sherlock Holmes. He certainly incarnates a prototype of a detective (prototype as that to look to copy, not in the meaning of unfinished that the word might have). Sherlock possesses the specifics knowledge of a “field” investigator; that is, he performs scientific studies on the crime scenes (and at the time in which the stories are set, criminalistics was in its dawn) and has attempted to gather (as showed in A study in Scarlet and in The Five Orange Peeps with the list of his knowledge confectioned by Watson) all the knowledge that a detective is likely to require, and it is demonstrated several times how this helps him while the police lacks this elements. And of course, he has taught himself his famous observational and deductive skills, mastering them to a very high degree (though his brother Mycroft is better at this than him).

Watson accounts in A Scandal in Bohemia the effect that Holmes has in him and which also has in the readers:

apart from the nature of the investigation which my friend had on hand, there was something in his masterly grasp of a situation, and his keen, incisive reasoning, which made it a pleasure to me to study his system of work, and to follow the quick, subtle methods by which he disentangled the most inextricable mysteries.

Comparing him with Dupin, Sherlock combines theory with practice more than Dupin does in his three stories because Holmes conducts much more fieldwork. Even though it is said that he solves cases without leaving his house, in most of the cases narrated by Watson, his field investigations—often far superior to those of the police—are essential for obtaining the necessary data to discover or prove things. Dupin, on the other hand, explains his reasoning from an angle that I’m not sure qualifies as epistemological, but at least I think this word gives the general idea. He explains his processes from the most basic level in a way that Sherlock only does in detail in A Study in Scarlet and then sporadically throughout his stories.

In a way, while Dupin does need to get out of the house to solve the crimes in his three stories, this trilogy emphasizes the basic science of detection, while the stories of Holmes focus more on applied science, and so they are complementary.

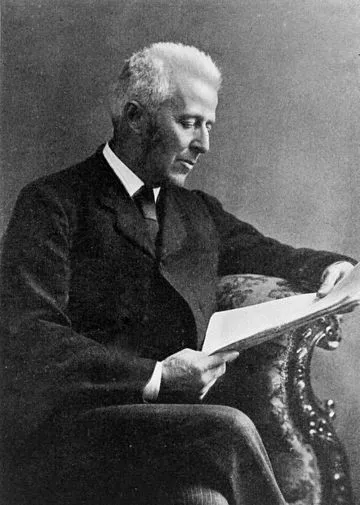

Finally, a remark of what Dr. Bell says in a foreword for A Study in Scarlet, informing before it that this doctor was one of Conan Doyle’s medicine professors and it could be said that he was the real Sherlock Holmes, as he impressed Doyle profoundly (Ver en Wikisource) (as well as he could be a real version of dr House, the twenty first century Sherlock Holmes of medicine fiction):

Says dr Bell:

He [Doyle] makes him [Holmes] explain to the good Watson the trivial, or apparently trivial, links in his chain of evidence. These are at once so obvious when explained, and so easy, once you know them, that the ingenuous reader at once feels, and says to himself, I also could do this; life is not so dull after all; I will keep my eyes open, and find out things.

And Bell also praises correctly Doyles’ writing abilities:

He has had the wit to devise excellent plots, interesting complications; he tells them in honest Saxon-English with directness and pith; and above all his other merits, his stories are absolutely free from padding. He knows how delicious brevity is, how everything tends to be too long, and he has given us stories that we can read at a sitting between dinner and coffee, and we have not a chance to forget the beginning before we reach the end.

Two more points:

One, I share with you an unprovable hypothesis: I think likely that, while Sherlock Holmes was already a big phenomenon by the time of his match against professor Moriarty, his epic death in this great short story was a tremendous push to increase his popularity even more and consolidate it because the uproar (whether or not people used black ribbons in the streets afterwords) would have call the attention of people who had not read it yet. It would have caused curiosity on why the death of a fictional detective was of such impact, as well as, years later, why there was a bunch of people waiting in line in the street to obtain a new novel of Sherlock Holmes (The Hound of the Baskervilles).

Two, in 1911 Ronald Knox gave a conference at the Trinity College of Oxford conceptualizing what he called “The game”, consisting of pretending that Sherlock Holmes was a real person and explain from there inconsistencies or hollows in the stories, and as there are several of them because Conan Doyle cared about the dramatic effect but did not dwell much on details, this game is a very amusing one to entertain the fans.

¿Have you read the Sherlock Holmes stories?

All images but dr Bell's are from wikimedia commons