Warning Note: This post will contain both spoilers and topics that might not be suited for all. Please proceed with caution if you want to read the book without it being spoiled, and if you are a sensitive reader. The nature of this book is violent.

Questions and More Questions

What does it mean to be free? What does the choice for something against something else entail? What does this say about us, humans, who supposedly choose things freely? Can we in fact ever be free from influences, outside or familial, government or corporate? How much can the government interfere with our choices? How does the interplay between free choices and consequences play out in the ideal society we want to live in? Can the utopian idea of a society free from troubles ever exist?

These are only some of the questions that popped into my head while I thought about the book A Clockwork Orange, written by Anthony Burgess, after I closed it. Classics are classics for a reason, it leave you pondering existential questions, ones that few other people ask. These books leave a permanent "stain" on you, and I use stain here for the obvious reason, that is, that "stain" is itself not always positive.

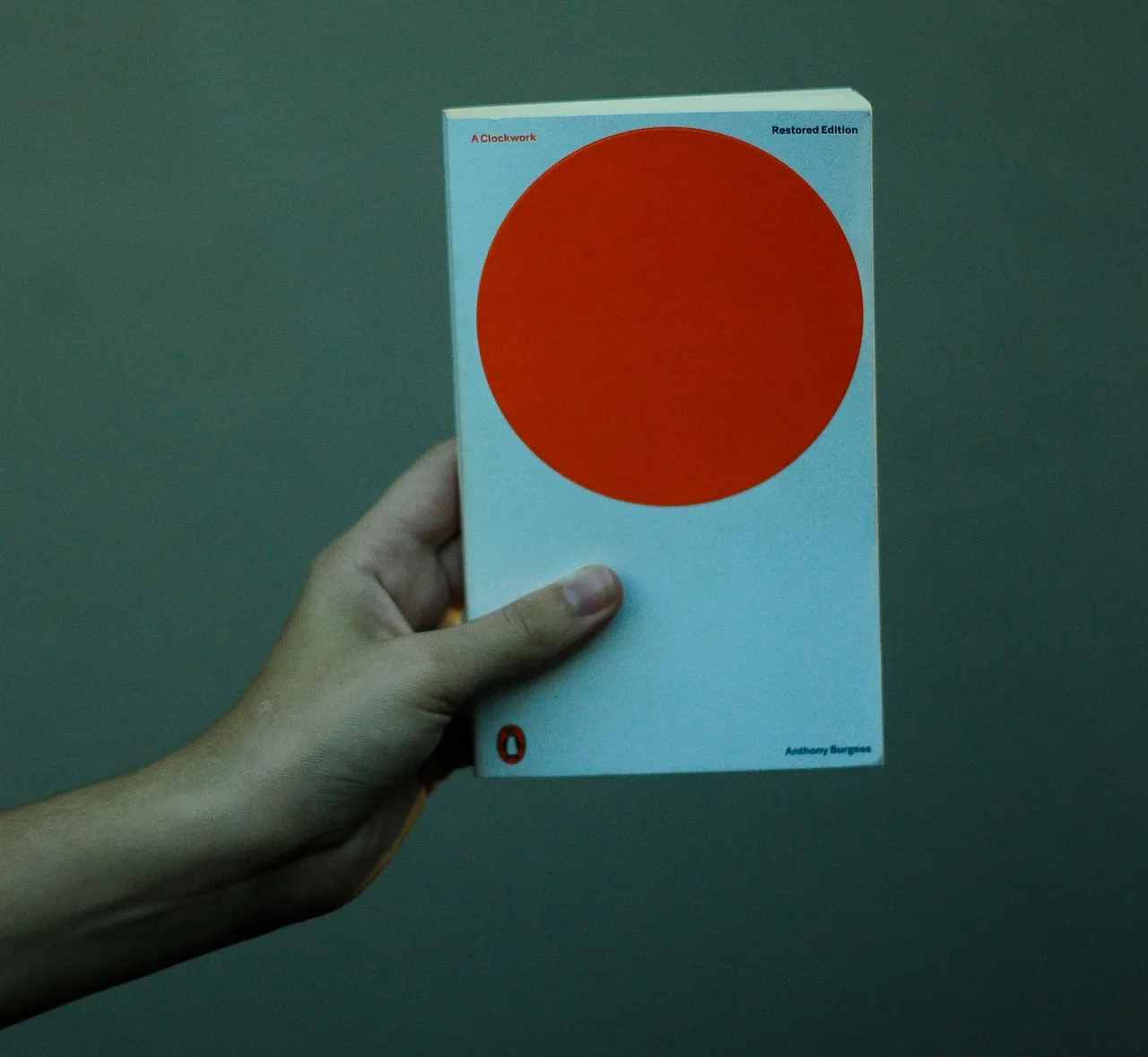

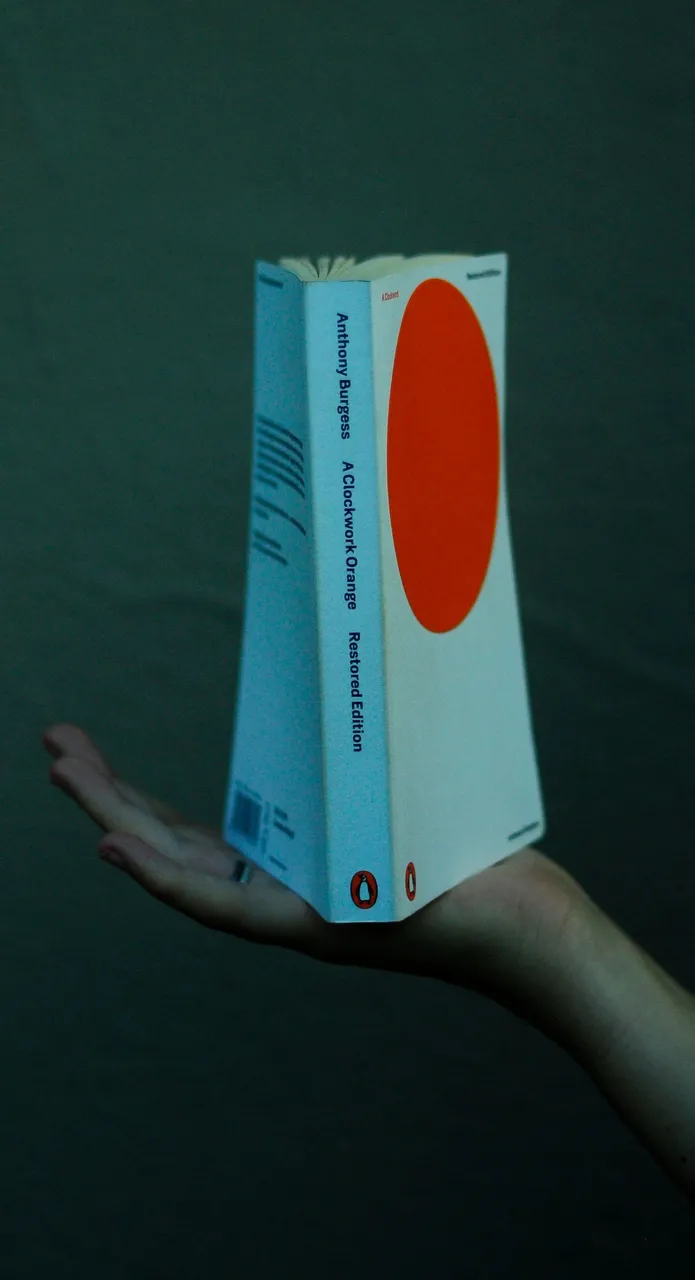

A Clockwork Orange is one of those strange books you just have to read. You can watch the movie, which does some justice to the book, especially in forming the lead character, but the movie gets way too much wrong, leading you with the wrong impressions. If you can find this restored edition by Penguin books, there are incredibly useful essays in the back of the book that deals with this topic, especially how the movie got the book wrong.

That said, let me dive head first into this incredibly graphic novel (for its time) and my impressions. It is a fundamentally philosophical piece of fiction with real-world implications, so a book right up my alley as a self-proclaimed philosopher!

A Hard Read

Let me start off with the obvious first, this is not an easy read, for two reasons.

Firstly, Burgess, a linguist and lover of languages, developed his own dialect for the book, called "nadsat". The narrator conveys the narrative in this dialect, consisting of, amongst others, Russian, different English slang words, and words developed from the mere sound of Russian into English. For example, the word for "good" in nadsat is "horrorshow", which apparently comes from the Russian pronunciation of "khoroshiy/khorosho", which means good. If you listen carefully to the pronunciation, one can figure out how Burgess got to "horrorshow". This is, at first, rather bothersome for the reader, but most of the meanings of these words can be deduced or derived from their usage in context. There is an appendix with most of the meanings that help with reading the book, but apparently, Burgess did not like this as he wants the reader to be confused, to deduce meaning for yourself.

The second reason why this is not an easy read, is because of the conflict you as the reader feel with sympathizing with a character that is inherently bad. This is something that does not come through in the movie as it does in the book. The character is really not a good person, choosing violence for the sake of violence and not feeling anything for it. I am hesitant to say this, especially because the narrator is still so young, but he gives me psychopath feelings. This will become clear in my review of this book.

To Choose or Not to Choose

What makes us human? This is the central question of this book. The answer to this question is choice. Our being able to choose is what makes us human.

The narrator, Alex, constantly chooses violence as a means of having fun. The novel is set in a dystopian future in which these nadsat teens are ruling the streets with what Alex calls "ultra-violence". We witness, through the eyes of Alex, brutal murders, violent rapes, and general savage behaviour. These are always given as choices to the reader. Alex is always choosing to do the bad things. Multiple times throughout his rampages, there is always the conscious choice he makes toward these acts of ultra-violence.

There is a scene in which he kills an old lady when he enters her home. Before this, however, he struggled to get the old lady to open her door, therefore the need to climb through the window. He could have just left, he could have chosen to not do the ultra-violent acts. But he did not. He willfully and consciously chose to do it. This is a small detail that the reader might miss.

When Alex is eventually sent to jail, he gets the choice to lead a "free" life if he is subjected to extreme forms of rehabilitation and conditioning. He chooses for this experimental treatment, and in doing so, his ability to choose for ultra-violence is taken away from him. Or more specifically, he cannot get violent as this creates a near-death sickness in him that prohibits him from choosing violence. Sadly, this conditioning also included classic music, as he loved classic music, especially Beethoven. So every time he hears the music or wants to act violently, he gets sick and therefore opts not to choose violence (or classical music).

The priest in the book made a big scene about this conditioning, as for him and his Christian worldview are premised on freedom of choice. With the conditioning of Alex, he ceases to be "human" in the Christian worldview as he cannot make a choice any longer. So, Burgess places the reader in a precarious and strange position: we are human because we can choose. But this leads to the option between choosing good and bad, or the one is premised on the other; you cannot be good without having the choice between being good or bad. One without the other relinquishes us humans to be good or bad.

And this is the moral conundrum Burgess puts us in when he wants us to sympathise with Alex. We need to see that having the choice of doing good or bad is a prerequisite for being good or bad. When we lose the ability to choose, we are doomed.

And this is illustrated through the novel. Violence is thus not seen as the dystopia in which Alex and the characters are situated, instead, the dystopia is in us losing the ability to choose. Because being conditioned to do the "right" thing is not a choice for doing the right thing.

What Society do you Want to Live In?

In the end, we can ask the simple question: in what society do we want to live in? Do we prefer the dystopia in which everyone is conditioned to do the "right" thing? Or do we choose the "dystopia" in which violence is always around the corner?

In some sense, we are already in a dystopia where we are conditioned to do the "right" thing, I would argue. Let me briefly justify this position in concluding this review. Doing the right thing is very subjective. Who gets to say what the morally right thing to do is a problem philosophers have dealt with for thousands of years. No answer will soon follow. But the political problem is that someone will always be on the "wrong side" and who gets to judge who is on the right and wrong side of the judgement is where we need to tread very cautiously.

Take, for example, modern "cancel culture" as it has come to be known. The judge in this case is the collective voice (on Twitter or Instagram). But the very fear of being cancelled conditions us to live according to the standard of not being judged. Hence, conditioning our behaviour. As this is still an ongoing "social experiment" of our making, the full consequences are still somewhat unknown. But the fact remains that our ability to choose is taken away, we need to act, we need to think in a certain way, and so on.

Burgess leaves us rather unsatisfied with the conclusion of the book. If he had the vantage point we have today, he might have chosen a different conclusion to his narrative. But this is up for speculation.

Postscriptum, or Did It Happen Like They Predicted?

Various dystopian novels exist in the literature or the classics. A brave new world, 1984, a Clockwork Orange... But did any of these get the future right? Probably not, but they remain worthwhile to read.

If you are into these dystopian novels, grab this one, and all the other classics while you are at it! They offer a unique insight into the minds of older generations who probably struggled with the idea of change and then uncertainties of the future.

For now, happy reading, and keep well!

All of the writing and musings in this post are my own. The opinions are also my own. The photographs are also my own, taken with my Nikon D300. Thank you @urban.scout for being my model in the photographs.