Blanco con bata, doctor; negro con bata, chichero.

Dicho vulgar venezolano

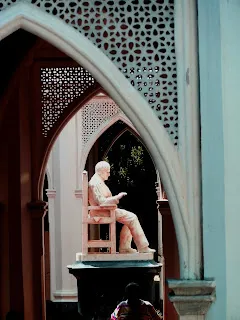

Cuando uno viene desde los estadios hacia la estación del metro de Ciudad Universitaria, al final de la isla de esa avenida que creo que se llama Las Acacias, hay una plazoleta donde puede verse la estatua de un hombre ataviado con algo que parece una bata desabotonada. Si se hiciera una encuesta al pie de este monumento y se le preguntara a los transeúntes quién es el personaje en cuestión, lo más probable es que muy pocos podrían identificarlo.

When one comes from the stadiums to the Ciudad Universitaria subway station, at the end of the median strip of what I believe is called Las Acacias Avenue, there is a small square where one can see a statue of a man wearing something that looks like an unbuttoned robe. If a poll were taken at the foot of this monument and passersby were asked who the personage in question is, it is likely that very few would be able to identify him.

No es de extrañar. La falta de memoria histórica nos caracteriza como pueblo. Es un mal probablemente incurable. Pero digamos rápidamente que se trata de un personaje fundamental, un hito en la Historia con hache mayúscula del país, una figura además cuya historia personal es apasionante y polémica y tiene un final trágico. Se trata de Rafael Rangel, el bachiller que nunca llegó a ser doctor por ser negro e hijo ilegítimo, como el 70% de la población de Venezuela, según se dice y se repite constantemente por ahí.

No wonder. The lack of historical memory characterizes us as a people. It is probably an incurable disease. But let's quickly say that this is a fundamental character, a milestone in the country's history with a capital H, a figure whose personal history is exciting and controversial and has a tragic ending. He is Rafael Rangel, the high school graduate who never became a doctor because he was black and an illegitimate son, like 70% of the Venezuelan population, as it is said and constantly repeated.

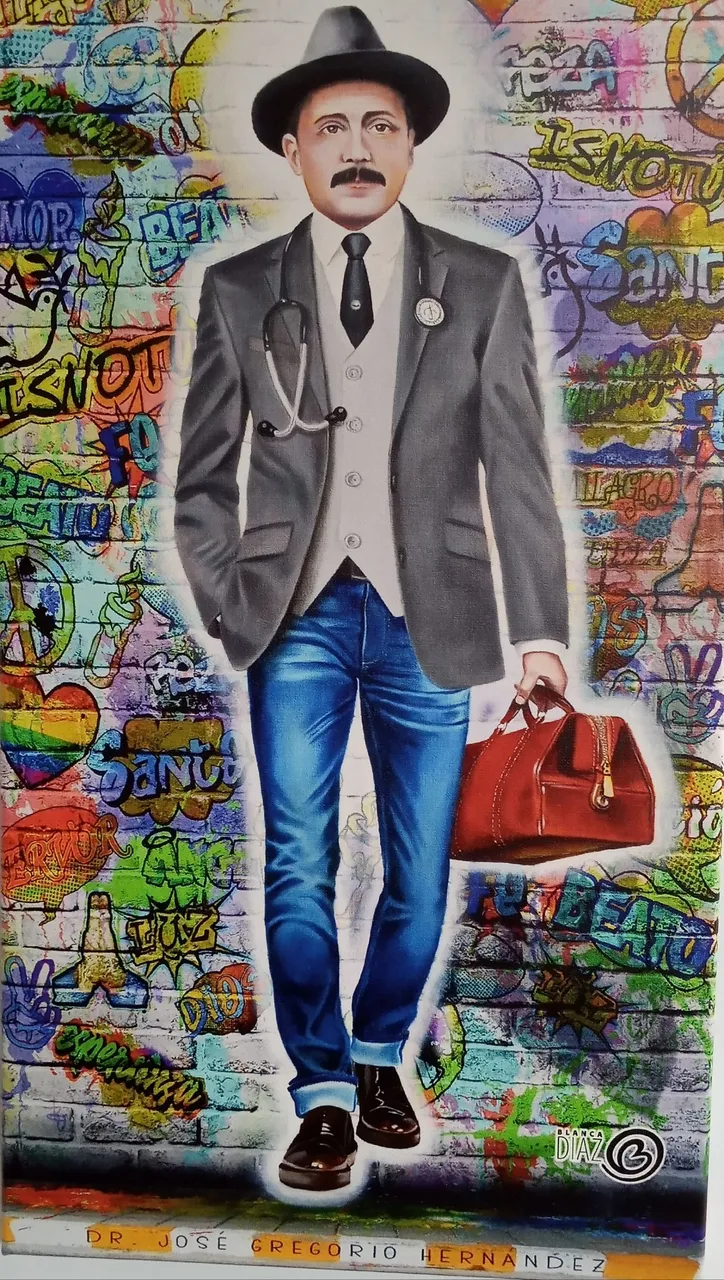

Siempre he pensado que la historia de Rafael Rangel merece ser contada en una película (porque esta última es una forma narrativa con el potencial de llegar a una audiencia masiva, aunque tantos venezolanos lamentablemente —y quizás justificadamente— aborrezcan el cine nacional). Podría ser un documental minucioso y exhaustivo como los que hizo Manuel de Pedro en los 70. O una reconstrucción histórica (como las que hacen magistralmente, hay que reconocerlo, los ingleses) de la Venezuela de los primeros años del siglo XX, con tres personajes principales: ante todo, el propio Rangel como protagonista. El segundo lugar, por contraste, lo ocuparía una figura que todo el mundo reconoce, ya que es parte entrañable de nuestra iconografía popular y expresión de nuestro gran complejo de inferioridad nacional, de nuestra frustración y hambre de reconocimiento que se retuerce ante la tozudez de la iglesia católica romana, que sigue negándose a oficializar a nuestro primer santo venezolano. Como si el reconocimiento del pueblo no fuera suficiente. Tal vez al Vaticano no le gusta el aura de curandero-mandinga que ha adquirido. ¿O será que el abogado del diablo ha descubierto cosas que no nos quieren decir?

I have always thought that Rafael Rangel's story deserves to be told in a film (because the latter is a narrative form with the potential to reach a mass audience, although so many Venezuelans unfortunately -and perhaps justifiably- abhor national cinema). It could be a thorough and exhaustive documentary like those made by Manuel de Pedro in the 1970s. Or a historical reconstruction (like those masterfully done, admittedly, by the English) of Venezuela in the early years of the 20th century, with three main characters: first and foremost, Rangel himself as the protagonist. The second place, by contrast, would be occupied by a figure that everyone recognizes, since he is an endearing part of our popular iconography and an expression of our great national inferiority complex, of our frustration and hunger for recognition that writhes in the face of the stubbornness of the Roman Catholic Church, which still refuses to make official our first Venezuelan saint. As if the recognition of the people were not enough. Maybe the Vatican doesn't like the aura of a priest-mandinga that he has acquired, or could it be that the devil's advocate has discovered things that they don't want to tell us?

Aparte de su condición de pioneros, héroes e incluso mártires de la ciencia médica en Venezuela, el bachiller Rangel y el doctor José Gregorio Hernández tienen otra cosa en común: ambos son andinos, provenientes de dos poblaciones muy cercanas entre sí del estado Trujillo (Betijoque e Isnotú). Ambos aparecen en el preciso momento en que los andinos finalmente reclamaban el protagonismo que les correspondía por derecho propio en nuestra tragicómica historia, de la mano del tercer gran protagonista que propongo para mi sainetesca película: Cipriano Castro, el Caudillo Restaurador del Liberalismo, a quien no deberíamos permitir que su reciente reivindicación moral le quite nada de su patética humanidad.

Apart from their condition as pioneers, heroes and even martyrs of medical science in Venezuela, the bachelor Rangel and Dr. José Gregorio Hernández have something else in common: they are both Andean, coming from two towns very close to each other in the state of Trujillo (Betijoque and Isnotú). Both appear at the precise moment when the Andeans were finally claiming their rightful protagonism in our tragicomic history, hand in hand with the third great protagonist that I propose for my sainetesque film: Cipriano Castro, the Caudillo Restorer of Liberalism, whose recent moral vindication should not be allowed to take away any of his pathetic humanity.

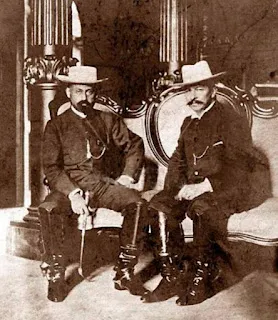

Al morir Joaquín Crespo (1898), el país se quedó sin Macho Alfa, y los diversos machos rivales se enzarzaron en una lucha sin cuartel por la jefatura indiscutible de la manada nacional. Cipriano decidió que él tenía el coraje y la capacidad para derrotarlos a todos, y no sólo lo consiguió, sino que fundó una dinastía tachirense que iba a dominar el naciente siglo XX. Como dice Mariano Picón Salas, entre los 60 compañeros que venían con Cipriano desde el Táchira había tres futuros presidentes de Venezuela, los tres primeros de la mentada dinastía: el propio Castro, su compadre Juan Vicente Gómez, y un quinceañero llamado Eleazar López Contreras. Por cierto, en la película hay que darle un papel secundario pero decisivo a Gómez. Y hay que ser justos con ambos personajes: Cipriano, juerguista y parrandero, tiene una tendencia a la prosopopeya que lo hace caricaturesco. Por su parte, Gómez, en la plenitud de su vigor, tiene una tremenda pinta de galán y no parece un vejete repugnante y adulador. ¿Se puede ser imparcial ante el peor tirano de nuestra historia (que lo fue) y poner en la balanza sus pros y sus contras? Porque no existe un “lado correcto de la historia”, esa expresión horrenda que se oye por ahí últimamente.

When Joaquín Crespo died (1898), the country was left without an Alpha Male, and the various rival males engaged in an all-out struggle for the undisputed leadership of the national herd. Cipriano decided that he had the courage and the capacity to defeat them all, and not only did he succeed, but he founded a Tachira dynasty that was to dominate the nascent 20th century. As Mariano Picón Salas says, among the 60 comrades who came with Cipriano from Táchira there were three future presidents of Venezuela, the first three of the aforementioned dynasty: Castro himself, his compadre Juan Vicente Gómez, and a fifteen year old named Eleazar López Contreras. By the way, Gómez has to be given a secondary but decisive role in the film. And we must be fair with both characters: Cipriano, a party animal, has a tendency to prosopopopoeia that makes him caricatured. On the other hand, Gomez, in the fullness of his vigor, has a tremendous gallant look and does not look like a disgusting and sycophantic old man. Can one be impartial before the worst tyrant in our history (which he was) and weigh his pros and cons? Because there is no "right side of history", that horrendous expression you hear around lately.

Aprovecho para criticar brevemente la película La Planta Insolente, que me parece terriblemente fastidiosa como todos los “biópicos” (término hollywoodense que fusiona lo biográfíco con lo épico). Encuentro mucho más interesante narrar un episodio breve que involucre a personajes relativamente secundarios de la escena histórico-política del momento (una especie de historia desde abajo), con breves y ocasionales apariciones de las grandes figuras, que hacen sentir su poder, pero como parte del background de la historia que se está narrando. Antes de pasar de una vez a echar el cuento de Rangel, digamos que empieza mientras Venezuela aún está dominada por un Castro aparentemente omnipotente, que ha derrotado a todos sus enemigos, internos y externos; y termina después de que su hasta entonces fiel lugarteniente Gómez, aprovechando la salida del país de su compadre para curar su riñón enfermo, lo desaloja del poder.

I take this opportunity to briefly criticize the film The Insolent Footstep, which I find awfully tiresome like all "biopics" (a Hollywood term that merges the biographical with the epic). I find it much more interesting to narrate a brief episode involving relatively secondary characters of the historical-political scene of the moment (a sort of history from below), with brief and occasional appearances of the big figures, who make their power felt, but as part of the background of the story being narrated. Before going on to tell Rangel's story, let us say that it begins while Venezuela is still dominated by an apparently omnipotent Castro, who has defeated all his enemies, internal and external; and it ends after his until then faithful lieutenant Gómez, taking advantage of his compadre's departure from the country to cure his diseased kidney, removes him from power.

Empecemos la historia por el final, como recomienda Marcel Roche en su libro. Rafael Rangel, prestigioso jefe del flamante laboratorio del Hospital Vargas de Caracas, aparece con su bata blanca desabotonada, ingiriendo una dosis mortal de cianuro de potasio. ¿Por qué un joven tan talentoso, respetado por sus colegas y (hasta ese momento) protegido por los poderosos, decide matarse de un modo tan patético? Como decía Cantinflas, “hasta la pregunta es necia”: El talento siempre ha engendrado envidias, y más en un medio tan mezquino como el nuestro, donde las nulidades engreídas siempre se han enseñoreado. Con la caída de Castro, las alabanzas que habían llovido sobre Rangel se convirtieron en chismes e intrigas, y para los nuevos poderosos pasó de ser una eminencia a una rémora del gobierno anterior.

Let's start the story at the end, as Marcel Roche recommends in his book. Rafael Rangel, prestigious head of the brand new laboratory of the Vargas Hospital in Caracas, appears with his white coat unbuttoned, ingesting a lethal dose of potassium cyanide. Why would such a talented young man, respected by his colleagues and (until that moment) protected by the powerful, decide to kill himself in such a pathetic way? As Cantinflas used to say, "even the question is foolish": Talent has always engendered envy, and even more so in such a petty environment as ours, where conceited nullities have always ruled the roost. With the fall of Castro, the praises that had been showered on Rangel turned into gossip and intrigues, and for the new powerful he went from being an eminence to a remnant of the previous government.

Rangel era hijo ilegítimo de un comerciante de Betijoque. Su madre murió poco tiempo después de su nacimiento y fue reconocido por su padre (es decir, le dio su apellido), quien entonces lo llevó a vivir con su familia legítima al cuidado de su esposa, que para Rafael era una madrastra. Todo esto es una historia muy común en Venezuela. Sus rasgos no eran negroides, sino más bien mestizos (alguien dijo que parecía un hindú de tez morena y cabello negro lacio). Con el apoyo de su padre, llegó a Caracas a estudiar medicina, terminando dos años de la carrera con buenas calificaciones. En ese momento se le ofreció la oportunidad de trabajar en el recién creado laboratorio clínico del Hospital Vargas, dirigido por el doctor José Gregorio Hernández. Allí, Rangel se entregó a la labor investigativa, mucho menos glamorosa que los estudios de medicina. Entre esputos, excrementos, orina, pus y otras secreciones corporales descubrió la belleza de la microbiología y se convirtió en pionero de lo que hoy en día llamaríamos “bioanálisis”. Entre 1902 y 1907, sus investigaciones y publicaciones como patólogo y microbiólogo fueron tan destacadas que mereció ser promovido a jefe del laboratorio, el cual estaba bajo la protección directa del gobierno de Cipriano Castro, quien no vacilaba en asignar importantes sumas para su dotación y modernización. Y entonces se presentó el episodio que resultaría decisivo en la carrera (y en la tragedia) de Rangel: el estallido de la epidemia de peste bubónica en la Guaira en 1908.

Rangel was the illegitimate son of a merchant from Betijoque. His mother died shortly after his birth and he was acknowledged by his father (i.e. he gave him his last name), who then took him to live with his legitimate family in the care of his wife, who for Rafael was a stepmother. All this is a very common story in Venezuela. His features were not negroid, but rather mestizo (someone said he looked like a Hindu with a dark complexion and straight black hair). With his father's support, he came to Caracas to study medicine, finishing two years of the career with good grades. At that time he was offered the opportunity to work in the newly created clinical laboratory of the Vargas Hospital, directed by Dr. José Gregorio Hernández. There, Rangel devoted himself to research work, much less glamorous than medical studies. Among sputum, excrement, urine, pus and other bodily secretions, he discovered the beauty of microbiology and became a pioneer of what today we would call "bioanalysis". Between 1902 and 1907, his research and publications as a pathologist and microbiologist were so outstanding that he deserved to be promoted to head of the laboratory, which was under the direct protection of the government of Cipriano Castro, who did not hesitate to allocate important sums for its endowment and modernization. And then came the episode that would prove to be decisive in Rangel's career (and tragedy): the outbreak of the bubonic plague epidemic.

La peste, el cuarto jinete del Apocalipsis, representa uno de los miedos atávicos de la humanidad. Como se sabe, la transmite una pulga que vive como parásita de la rata negra. Cuando la pulga se infecta con el bacilo de la peste, mata a las ratas donde vive normalmente, y entonces pasa a chuparle la sangre al hombre. La peste ha arrasado Europa y Asia varias veces, matando millones. Las ratas la transportan en los barcos, por eso los puertos suelen ser los primeros sitios donde se presenta. La señal inconfundible de su llegada es que empiezan a morir las ratas. Como secuela de la gran peste de Hong Kong en 1896, diseminada en otros puertos del Atlántico y el Pacífico en los años siguientes, las ratas empezaron a morir en el puerto de La Guaira a principios de 1908.

The plague, the fourth horseman of the Apocalypse, represents one of mankind's atavistic fears. As is well known, it is transmitted by a flea that lives as a parasite of the black rat. When the flea is infected with the plague bacillus, it kills the rats where it normally lives, and then goes on to suck the blood of man. The plague has ravaged Europe and Asia several times, killing millions. Rats carry it on ships, which is why ports are usually the first places where it shows up. The unmistakable sign of its arrival is that the rats begin to die. In the aftermath of the great plague of Hong Kong in 1896, which spread to other Atlantic and Pacific ports in the following years, rats began to die in the port of La Guaira in early 1908.

La reacción de los gobiernos ante la sola mención de la palabra peste es lo que los psicoanalistas llaman mecanismo de negación, porque saben que implica tomar medidas impopulares y ruinosas como la cuarentena, el cierre de puertos y la incineración de cadáveres y propiedades. Castro, que había sido llamado el Salvador de la República, adoptó la misma consabida actitud: en su gobierno no podía ocurrir aquella calamidad. Cuando los rumores aumentaron y aparecieron los primeros muertos, se comisionó a Rafael Rangel para que bajara a La Guaira a constatar si aquello era o no era peste, con la clara esperanza de que no lo fuera. Es interesante el hecho de que se enviara a Rangel, que no era doctor sino apenas bachiller, y no a José Gregorio Hernández, profesor de bacteriología de la Universidad Central de Venezuela. Según Roche, la razón es que Hernández estaba pasando por una crisis de vocación religiosa muy profunda, que lo impulsaría, aún en medio de aquella situación de emergencia, a salir del país para ingresar como monje cartujo en un monasterio en Italia (experiencia que, como se sabe, terminaría siendo fallida). En vista de aquella circunstancia, Rangel fue considerado más competente y mejor equipado que su maestro.

The reaction of governments to the mere mention of the word plague is what psychoanalysts call a denial mechanism, because they know that it implies taking unpopular and ruinous measures such as quarantine, closing of ports and incineration of corpses and property. Castro, who had been called the Savior of the Republic, adopted the same familiar attitude: that calamity could not happen in his government. When rumors increased and the first deaths appeared, Rafael Rangel was commissioned to go down to La Guaira to verify whether or not it was a plague, with the clear hope that it was not. It is interesting that Rangel, who was not a doctor but only a bachelor, was sent instead of José Gregorio Hernández, professor of bacteriology at the Central University of Venezuela. According to Roche, the reason was that Hernández was going through a very deep religious vocation crisis, which would drive him, even in the midst of that emergency situation, to leave the country to join a Carthusian monastery in Italy (an experience that, as is known, would end up being unsuccessful). In view of that circumstance, Rangel was considered more competent and better equipped than his master.

En La Guaira, Rangel despliega toda su actividad y experiencia, en contacto permanente con el propio presidente Castro por medio del telégrafo. Al principio, los cultivos e inoculaciones en animales de laboratorio no parecen indicar la presencia del bacilo de la peste; y estos resultados, aunados a la presión del gobierno y de la temerosa ciudadanía, llevan a Rangel a emitir un primer diagnóstico negativo. De momento se arma una gran alharaca y casi se le declara héroe nacional. Sin embargo, siendo un genuino científico que no buscaba los aplausos sino comprobar la verdad, siguió examinando nuevos casos, hasta que finalmente confirmó la presencia del temido bacilo. Enseguida telegrafió a Castro y tomó discretamente el tren a La Guaira, tratando de no alarmar innecesariamente a la población, para iniciar una heroica lucha contra la epidemia.

In La Guaira, Rangel deploys all his activity and experience, in permanent contact with President Castro himself by telegraph. At first, the cultures and inoculations in laboratory animals do not seem to indicate the presence of the plague bacillus; and these results, together with the pressure of the government and the fearful citizens, lead Rangel to issue a first negative diagnosis. For the time being, a great fuss is made and he is almost declared a national hero. However, being a genuine scientist who was not looking for applause but to prove the truth, he continued examining new cases until he finally confirmed the presence of the dreaded bacillus. He immediately telegraphed Castro and discreetly took the train to La Guaira, trying not to alarm the population unnecessarily, to start a heroic fight against the epidemic.

Ya este primer diagnóstico errado hacía prever el escándalo que se avecinaba. Cuando Castro decreta el cierre del puerto, la realidad se hizo inocultable. En medio del pánico generalizado, Rangel asume personalmente la dirección médica y administrativa del combate sanitario; con lo cual empieza a ganarse enemigos debido a las medidas extremas que tiene que tomar, entre ellas la quema de algunas viviendas infectadas. Entretanto, Castro y su gobierno apoyan moral y financieramente todo lo que hace. La batalla contra la peste termina oficialmente en mayo de 1908, cuando se reabre el puerto de La Guaira. Rangel y sus colaboradores reciben honores y condecoraciones.

Already this first misdiagnosis foreshadowed the coming scandal. When Castro decreed the closing of the port, the reality became undeniable. In the midst of the generalized panic, Rangel personally assumed the medical and administrative direction of the sanitary combat; with which he began to make enemies due to the extreme measures he had to take, among them the burning of some infected houses. Meanwhile, Castro and his government support morally and financially everything he does. The battle against the plague officially ends in May 1908, when the port of La Guaira is reopened. Rangel and his collaborators receive honors and decorations.

Pero el final de esa crisis coincide con el agravamiento de la enfermedad renal de Castro. Ningún médico venezolano se atreve a operarlo, y le recomiendan que viaje a Alemania a tratarse con un célebre especialista. Castro se embarca el 24 noviembre de 1908, y el 19 de diciembre su compadre toma el poder, para no soltarlo hasta su muerte 27 años después. Muchos enemigos dentro y fuera del país tenía Castro, muchos intereses poderosos cerraron la trampa sobre él. Y con su caída empezó el calvario de Rafael Rangel.

But the end of that crisis coincided with the worsening of Castro's kidney disease. No Venezuelan doctor dared to operate on him, and he was recommended to travel to Germany to be treated by a famous specialist. Castro embarked on November 24, 1908, and on December 19 his compadre took power, not to let go until his death 27 years later. Castro had many enemies inside and outside the country, many powerful interests closed the trap on him. And with his fall began the ordeal of Rafael Rangel.

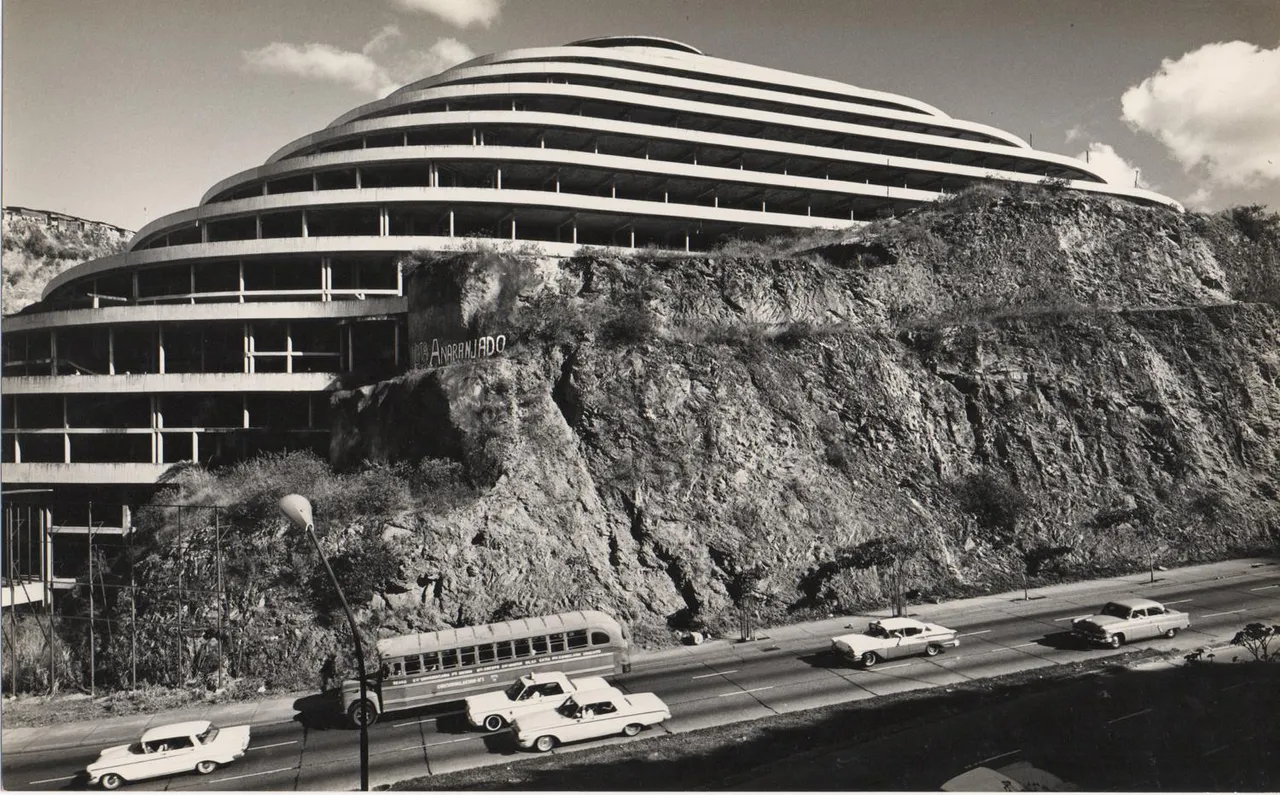

Es lo que yo llamo “el síndrome del Helicoide”: si lo hizo el gobierno anterior, no sirve, y hay que abandonarlo, o si es posible, destruirlo. De pronto empezaron a aparecer comentarios en la prensa: que cómo se le ocurría a Castro mandar a un simple bachiller a atender algo tan serio como la peste…que con razón se equivocó en el diagnóstico…se ponen en duda los métodos usados…se dice que gastó demasiado dinero inútilmente, que dónde estaban los reales…que se quemaron unas casas y nunca se pagaron…Rangel trató de responder a todo con dignidad. Pero había que cobrarle su identificación con Castro, sus cartas llenas de lealtad y admiración hacia el que ahora todos llamaban “tirano”. Y para colmo, la merecida beca que le habían ofrecido años atrás para ir a estudiar Patología Tropical a Europa, y que en ese momento, como dice Roche, le hubiera permitido alejarse de la hostilidad que el cambio de gobierno había desatado contra él en Caracas, le es negada terminantemente, como para confirmar su caída en desgracia.

It is what I call "the Helicoide syndrome": if the previous government did it, it is no good, and it must be abandoned, or if possible, destroyed. Suddenly, comments began to appear in the press: how could Castro think of sending a simple high school graduate to attend to something as serious as the plague...that he was rightly mistaken in his diagnosis...the methods used are questioned...it is said that he spent too much money uselessly, that the accounts did not add up...that some houses were burned and never paid for...Rangel tried to respond to everything with dignity. But he had to be charged for his identification with Castro, his letters full of loyalty and admiration for the one everyone now called "tyrant". And to top it all off, the well-deserved scholarship he had been offered years before to study Tropical Pathology in Europe, which at that time, as Roche says, would have allowed him to get away from the hostility that the change of government had unleashed against him in Caracas, was strictly denied, as if to confirm his fall in disgrace.

Quizás había en Rangel un profundo resentimiento a causa de su origen social; quizás había sido maltratado y humillado por esa razón. No sería de extrañarse. Quizás tenía una tendencia a la depresión y al suicidio…Quizás tenía enemigos que aprovecharon las circunstancias para “hacer leña del árbol caído”. Quizás hasta lo habrán llamado “negro”, y no precisamente por cariño. Sólo se puede elucubrar al respecto. Uno de los anexos del libro de Roche trata de las discusiones e interpretaciones de los psicólogos sobre la personalidad de los suicidas. Ahí se dice que muchos grandes investigadores científicos han perdido a uno de sus progenitores en su primera infancia, como le pasó a Rangel con su madre: Newton, Kelvin, Lavoisier, Boyle, Huygens, Rumford, Madame Curie, Maxwell…

Perhaps there was a deep resentment in Rangel because of his social origin; perhaps he had been mistreated and humiliated for that reason. It would not be surprising. Perhaps he had a tendency to depression and suicide... Perhaps he had enemies who took advantage of the circumstances to "make wood from the fallen tree". Maybe they even called him "nigger", and not exactly out of affection. One can only speculate about it. One of the appendices of Roche's book deals with the discussions and interpretations of psychologists about the personality of suicides. There it is said that many great scientific researchers have lost one of their parents in their early childhood, as happened to Rangel with his mother: Newton, Kelvin, Lavoisier, Boyle, Huygens, Rumford, Madame Curie, Maxwell....

También hay muchos rumores maliciosos sobre una posible enemistad entre Rangel y José Gregorio Hernández, pero no existen pruebas documentales contundentes de ello. Por el contrario, se sabe que Hernández fue su maestro, que lo recomendó para trabajar en el laboratorio y siempre alabó sus trabajos. Por otra parte, se dice que el venerable doctor tenía un trato frío y distante, no sólo con Rangel, sino en general. Roche recoge como anécdota el comentario que dicen que hizo Hernández al saber de la tragedia de Rangel: “Se murió ese loco”. En medio del positivismo reinante en la época, la religiosidad de Hernández probablemente no era muy bien vista y pudo haberle hecho antipático a los ojos de algunos de sus colegas.

There are also many malicious rumors about a possible enmity between Rangel and José Gregorio Hernández, but there is no strong documentary evidence of this. On the contrary, it is known that Hernández was his teacher, who recommended him to work in the laboratory and always praised his work. On the other hand, it is said that the eminent doctor was cold and distant, not only with Rangel, but in general. Roche collects as an anecdote the comment that Hernández is said to have made when he heard about Rangel's tragedy: "That madman died". In the midst of the reigning positivism of the time, Hernández's religiosity was probably not very well regarded and could have made him unpleasant in the eyes of some of his colleagues.

Poco después del suicidio y del escándalo subsiguiente, un conocido de Rangel de nombre Salustio González Rincones presentó en el Teatro Caracas una pequeña obra dramática (llamada Las Sombras) donde se hacen vagas alusiones con nombres supuestos a un famoso doctor que emplea como limpiador en su laboratorio a un chico provinciano, que resulta muy buen estudiante y termina como jefe del laboratorio. Luego el chico demuestra científicamente la existencia de la peste, pero lo obligan a callarse para no estropear un baile que piensa dar el Presidente de la República. El doctor y un ministro corrupto aprovechan la situación para comprar todas las vacunas y hacer negocio cuando se anuncie la peste. Más tarde, intrigan para que expulsen al chico del laboratorio, argumentando que no sólo no es doctor, sino que para colmo es negro. El chico, por supuesto, termina envenenándose.

Shortly after the suicide and the subsequent scandal, an acquaintance of Rangel's named Salustio González Rincones presented at the Caracas Theater a short play (called Las Sombras) where vague allusions are made with assumed names to a famous doctor who employs as a cleaner in his laboratory a provincial boy, who turns out to be a very good student and ends up as head of the laboratory. Then the boy scientifically proves the existence of the plague, but he is forced to keep quiet so as not to spoil a ball that the President of the Republic is planning to give. The doctor and a corrupt minister take advantage of the situation to buy all the vaccines and do business when the plague is announced. Later, they intrigue to have the boy expelled from the laboratory, arguing that not only is he not a doctor, but to top it off, he is black. The boy, of course, ends up poisoning himself.

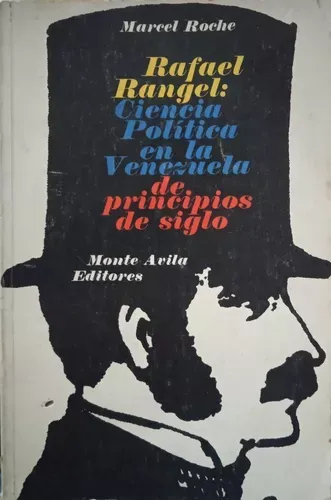

En fin, éste es el resumen de la tragedia de Rafael Rangel, pionero de los investigadores científicos de Venezuela, que prefirió ser un estudiante eterno en vez de graduarse de doctor, que vivió en carne propia los implacables vaivenes de la política y se quitó la vida a los 32 años, el 20 de agosto de 1909. Podría ser el tema de una interesante película documental, que rescataría la memoria de uno de los personajes menos reconocidos de la historia de Venezuela. Documental que nadie ha hecho todavía, que yo sepa. También da para un drama de época con estupendas posibilidades escénicas. Si algún estudiante de audiovisual siente interés por el tema, tendría que leerse el excelente libro del doctor Marcel Roche Rafael Rangel, ciencia y política en la Venezuela de principios de siglo, un magnífico estudio histórico con amplísima documentación. Además, recomiendo Días de Cipriano Castro de Mariano Picón-Salas. El blog El cronista de Tucutucu tiene información muy interesante y mucha bibliografía adicional. También es imprescindible el clásico de Albert Camus La peste.

In short, this is the summary of the tragedy of Rafael Rangel, a pioneer of scientific researchers in Venezuela, who preferred to be an eternal student instead of graduating as a doctor, who lived in the flesh the relentless ups and downs of politics and took his own life at the age of 32, on August 20, 1909. It could be the subject of an interesting documentary film, which would rescue the memory of one of the least recognized characters in the history of Venezuela. A documentary that no one has made yet, as far as I know. It could also be the subject of a period drama with great scenic possibilities. If any audiovisual student is interested in the subject, he/she should read Dr. Marcel Roche's excellent book Rafael Rangel, ciencia y política en la Venezuela de principios de siglo, a magnificent historical study with extensive documentation. I also recommend Días de Cipriano Castro by Mariano Picón-Salas. The blog El cronista de Tucutucu has very interesting information and a lot of additional bibliography. Albert Camus' classic La peste (The Plague) is also a must.

Muchas gracias a la comunidad Literatos por la acogida y los comentarios. Los felicito por su crecimiento y estoy encantado de publicar mis contribuciones con ustedes.