El 14 de diciembre de 1591 es la fecha de muerte del fraile San Juan de la Cruz, uno de los más importantes poetas de la literatura de habla hispana y alto exponente de la mística occidental junto a Santa Teresa de Jesús (o del Ávila). Su ardua labor reformadora de la Orden del Carmelo, acompañando a la monja citada, que diera lugar a los llamados Carmelitas Descalzos, así como su práctica de profunda espitualidad, estuvo jalonada por un intenso quehacer como escritor, el cual diera lugar a piezas capitales de la poesía y mística en lengua española.

December 14, 1591 is the date of death of the friar Saint John of the Cross, one of the most important poets of Spanish-speaking literature and a leading exponent of Western mysticism along with Saint Teresa of Jesus (or of Avila). His arduous reforming work of the Carmelite Order, accompanying the aforementioned nun, which gave rise to the so-called Discalced Carmelites, as well as his practice of deep spirituality, was marked by an intense work as a writer, which gave rise to capital pieces of poetry and mysticism in the Spanish language.

En su obra destaca: Cántico espiritual, Noche oscura y Llama de amor viva. Su escritura poética (también escribió comentarios en prosa a sus poemas) está influenciada por el texto bíblico, particularmente el libro Cantar de los Cantares, pero también por sus lecturas de obras clásicas anteriores y por la poesía de raíz popular (el romance).

Son numerosos los estudios realizados a su obra tanto desde el punto de vista literario como teológico. Yo he querido aprovechar esta fecha de conmemoración del poeta y místico español para difundir algunas reflexiones del poeta venezolano e internacional Rafael Cadenas recogidas en su libro Apuntes sobre San Juan de la Cruz y la mística.

Pero antes de pasar a ello (lo que haré en el siguiente post), reproduciré fragmentos de poemas de San Juan de la Cruz, respetando sus rasgos en las ediciones, que acompañaré de unos sucintos comentarios míos.

***

His work includes: Spiritual Canticle, Dark Night and Live Love Call. His poetic writing (he also wrote prose commentaries to his poems) is influenced by the biblical text, particularly the book Song of Songs, but also by his readings of earlier classical works and by poetry of popular roots (romance).

Numerous studies have been made on his work from both the literary and theological points of view. I wanted to take advantage of this date of commemoration of the Spanish poet and mystic to disseminate some reflections of the Venezuelan and international poet [Rafael Cadenas] collected in his book Apuntes sobre San Juan de la Cruz y la mística (Notes on St. John of the Cross and mysticism).

But before moving on to it (which I will do in the next post), I will reproduce fragments of poems by St. John of the Cross, respecting his features in the editions, which I will accompany with some succinct comments of my own.

De Cántico espiritual, que lleva por subtítulo “Canciones entre el Alma y el Esposo”, que está estructurado como un diálogo entre la Amada y el Esposo, unas pocas estrofas:

Esposa:

¿Adónde te escondiste,

amado, y me dejaste con gemido?

Como el siervo huiste,

habiéndome herido;

salí tras ti, clamando, y eras ido.

(…)

Y de todos cuantos vagan,

de ti me van mil gracias refiriendo,

y todos más me llagan,

y déjame muriendo

un no sé qué que quedan balbuciendo.

(…)

Mi amado, las montañas,

los valles solitarios nemorosos,

las ínsulas extrañas,

los ríos sonorosos,

el silbo de los aires amorosos,la noche sosegada,

en par de los levantes de la aurora,

la música callada,

la soledad sonora,

la cena que recrea y enamora.

Imitando a ese poema amoroso por excelencia que es el Cantar de los Cantares, hermoso libro del Antiguo Testamento de la Biblia judeocristiana, el poeta recrea la relación de deseo y necesidad de la amada por el amado. San Juan de la Cruz insistió en la interpretación religiosa, cristiana, como también se ha hecho con el referente bíblico, y para ello escribió una exégesis en prosa, mas, al igual que para el texto bíblico, se le podría dar una lectura desapegada de una perspectiva religiosa. Y así disfrutamos de imágenes de una sensorialidad única y de esas frases antitéticas (oxímoron, su nombre en retórica) por antonomasia que plenan la riqueza de su visión: “música callada”, “soledad sonora”.

From Spiritual Canticle, subtitled "Songs between Soul and Spouse", which is structured as a dialogue between Beloved and Spouse, a few stanzas:

Wife:

Where did you hide,

beloved, and left me groaning?

Like the servant you fled,

having wounded me;

I went out after thee, crying, and thou wast gone.

(...)

And of all those who wander,

of you a thousand graces are referred to me,

and all the more they call me,

and leave me dying

a I don't know what they remain stammering.

(...)

My beloved, the mountains,

the lonely valleys nemorosos,

the strange islands,

the sonorous rivers,

the whistling of the loving airs,the quiet night,

on par with the rising of the dawn,

the silent music,

the sonorous solitude,

the dinner that recreates and enamors.

Imitating that love poem par excellence which is the Song of Songs, beautiful book of the Old Testament of the Judeo-Christian Bible, the poet recreates the relationship of desire and need of the beloved for the beloved. St. John of the Cross insisted on the religious, Christian interpretation, as has also been done with the biblical reference, and for this he wrote an exegesis in prose, but, as for the biblical text, it could be given a reading detached from a religious perspective. And so we enjoy images of a unique sensoriality and those antithetical phrases (oxymoron, his name in rhetoric) by antonomasia that fill the richness of his vision: "quiet music", "sonorous solitude"._

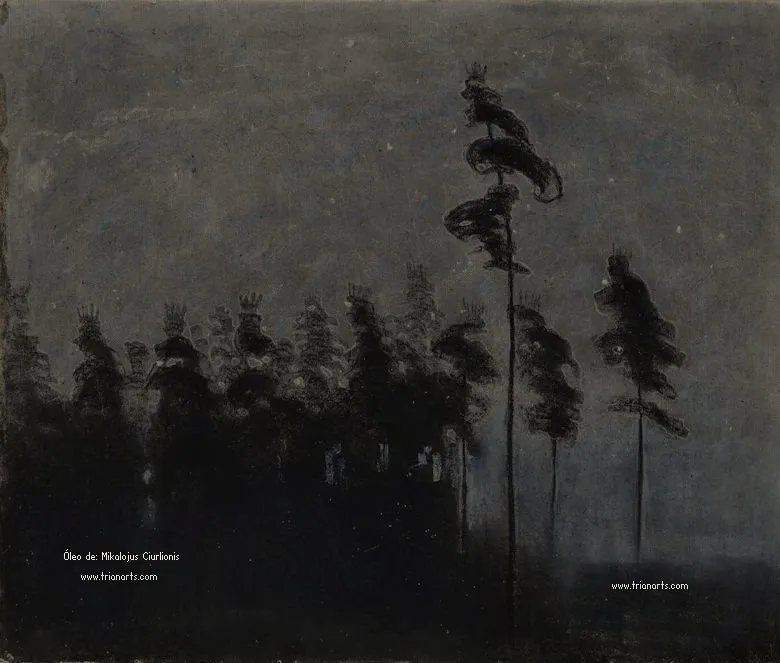

De Noche oscura, poema difundido como “Noche oscura del alma”, pues ella es la que habla, unos versos:

En una noche oscura,

con ansias en amores inflamada

¡oh dichosa ventura!,

salí sin ser notada,

estando ya mi casa sosegada.

(…)

sin otra luz y guía,

sino la que en el corazón ardía.

(…)

¡Oh noche que me guiaste!,

¡oh noche amable más que el alborada!,

¡oh noche que juntaste

amado con amada,

amada en el amado transformada!

(…)

y todos mis sentidos suspendía.

Quedéme y olvidéme,

el rostro recliné sobre el amado,

cesó todo, y dejéme,

dejando mi cuidado

entre las azucenas olvidado.

La motivación de este poema, como lo indica en la leyenda que el autor le escribiera, es imaginar el tránsito que hace el alma, en su proceso de unión con Dios, de la “noche de los sentidos” a la “noche del espíritu”. Nuevamente, las imágenes son de una belleza sensible únicas, dadas por su admirable sencillez, a lo que contribuyen la música de sus frases poéticas –por afinidades sonoras, más allá de la rima, reiteraciones, etc.– y el juego semántico que se nutre de evidenciar cualidades de las cosas (“noche oscura”).

From Dark Night, a poem spread as "Dark Night of the Soul", for it is she who speaks, a few lines:

_In a dark night,

with longing in love inflamed

O fortunate fortune!

I went out unnoticed,

my house being already quiet._

(...)

with no other light and guide

but that which burned in my heart.>

(...)

O night that guided me!

oh kind night more than the dawn,

oh night that you joined

beloved with beloved,

beloved in the beloved transformed!

(...)

and all my senses suspended.

I stayed and forgot myself,

I leaned my face on the beloved,

everything ceased, and I left me,

leaving my care

among the lilies forgotten._

The motivation of this poem, as indicated in the legend that the author wrote for it, is to imagine the transit that the soul makes, in its process of union with God, from the "night of the senses" to the "night of the spirit". Again, the images are of a unique sensitive beauty, given by admirable simplicity, the music of his poetic phrases -by sonorous affinities, beyond rhyme, reiterations, etc.- and the semantic game that is nourished by evidencing qualities of things ("dark night").

De Entréme donde no supe, que lleva por subtítulo “Coplas hechas sobre un extasi de harta contemplación”, unos fragmentos:

Entréme donde no supe,

y quedéme no sabiendo,

toda ciencia trascendiendo.

(…)

Estaba tan embebido,

tan absorto y ajenado,

que se quedó mi sentido

de todo sentir privado

(…)Este saber no sabiendo

es de tan alto poder,

que los sabios arguyendo

jamás le pueden vencer

Aquí el poeta escribió uno de los poemas más sensibles y complejos acerca de la experiencia del éxtasis místico, ese que también trató de transmitirnos Santa Teresa (ver la escultura de Bernini *). Con los recursos verbales de la paradoja (“saber no sabiendo”), tan propios del barroco español –al que ya se abría la obra de San Juan de la Cruz– y de la escritura mística en general, el poeta español nos pone en la línea de esa experiencia inefable de un saber otro, que el racionalismo científico omnímodo nunca aceptaría.

Y de otro famoso poema suyo, su primera estrofa:

Vivo sin vivir en mí,

y de tal manera espero,

que muero porque no muero.

From Enter me where I did not know, subtitled "Couplets made on an ecstasy of much contemplation", some fragments:

Enter me where I did not know,

and I stayed not knowing,

all science transcending._

(...)_

I was so absorbed,

so absorbed and oblivious,

that my sense was left

of all feeling deprived

(...)_This knowing without knowing

is of such high power

that the wise arguing

can never defeat it

(...)_

Here the poet wrote one of the most sensitive and complex poems about the experience of mystical ecstasy, which Saint Teresa also tried to transmit to us (see Bernini's sculpture *). With the verbal resources of paradox ("knowing without knowing"), so typical of the Spanish baroque -to which the work of St. John of the Cross already opened- and of mystical writing in general, the Spanish poet puts us in the line of that ineffable experience of an other knowledge, which the all-encompassing scientific rationalism would never accept.

And from another famous poem of his, his first stanza:

I live without living in me,

and in such a way I hope,

that I die because I do not die._

Referencias | References:

Cruz, San Juan de la (1977). Poesía completa | Complete poetry. Mexico: Edit. Aguilar.

Cadenas, Rafael (1995). Notas sobre San Juna de la Cruz y la mística | Notes on San Juan de la Cruz and mysticism. Caracas: Fondo Editorial Orlando Araujo / Federación de Asociaciones de Escritores de Venezuela.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_de_la_Cruz

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_of_the_Cross

======

Pueden acceder a la obra de San Juan y a otras referencias si consultan la fuente indicada, por ejemplo, por el portal de Cervantes Virtual, en este enlace*.

You can access San Juan's work and other references if you consult the indicated source, for example, through the Cervantes Virtual portal, at this link*.

La poesía de San Juan se ha llevado a la música, y hay muchas creaciones basadas en ella. Les ofrezco el ejemplo de una cantante que admiro, Loreena Mckennitt, que hizo una versión de "The dark night of the soul", de "La noche oscura del alma". Aquí el enlace a una edición subtitulada en español *.

St. John's poetry has been translated into music, and there are many creations based on it. I give you the example of a singer I admire, Loreena Mckennitt, who did a version of "The dark night of the soul", from "La noche oscura del alma". I leave you the link to a Spanish subtitled edition *

Gracias por su lectura. Thank you for reading.