1300 - 1400 : ABANDONMENT OF ROME

1400 - 1500 : CHURCH CORRUPTION

1500 - 1600 : CHURCH REFORMATION

1600 - 1700 : PROTESTANT REVOLT

1700 - 1800 : PROTESTANT LOSS OF FAITH

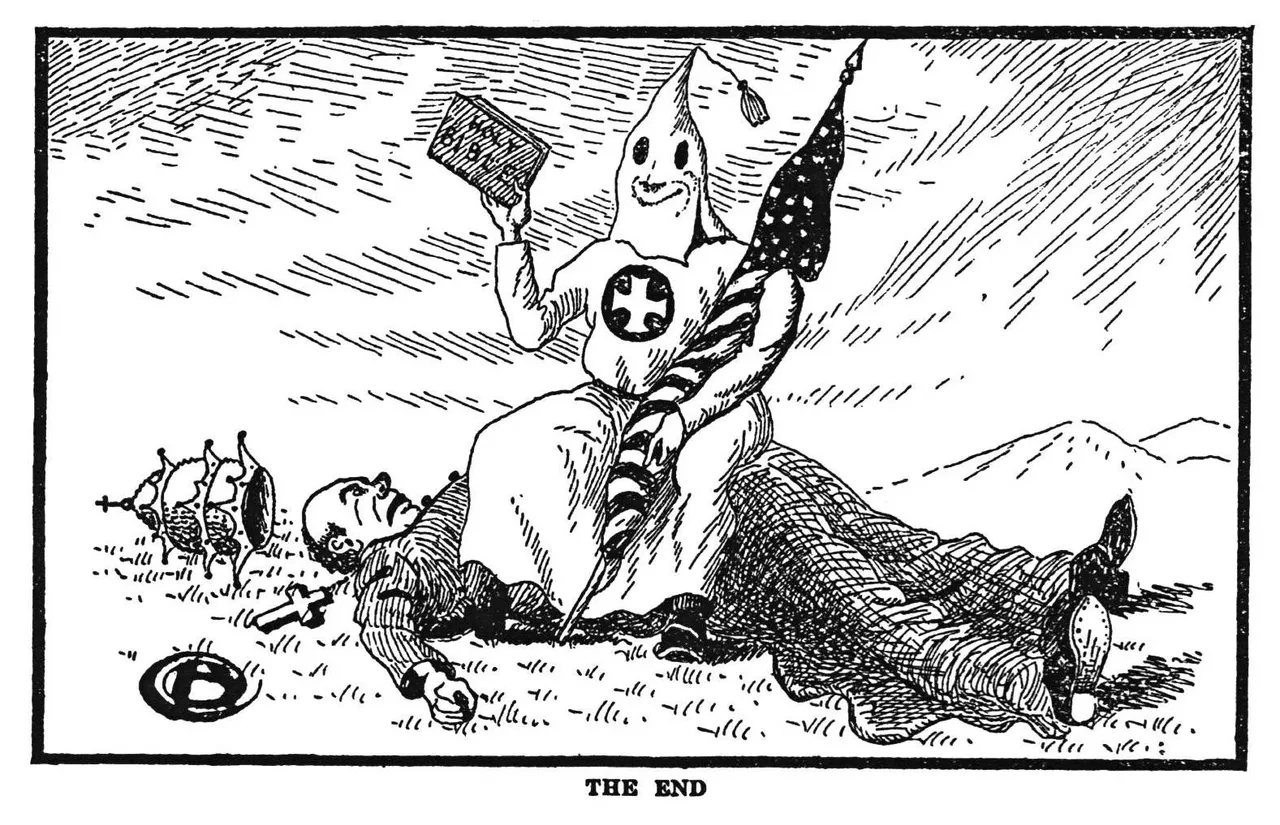

1800 - 1900 : PROTESTANT WORLDLY DOMINATION

"London and Berlin were the twin pillars of Protestant domination during the nineteenth century"

It is of first importance to appreciate this historical truth. Only a few of the most bitter or ardent Reformers set out to destroy Catholicism as a separate existing thing of which they were conscious and which they hated. Still less did most of the Reformers set out to erect some other united counter-religion.

They set out (as they themselves put it and as it had been put for a century and a half before the great upheaval) "to reform." They professed to purify the Church and restore it to its original virtues of directness and simplicity. They professed in their various ways (and the various groups of them differed in almost everything except their increasing reaction against unity) to get rid of excrescences, superstitions and historical falsehoods_of which, heaven knows, there was a multitude for them to attack.

In this second phase [1600 - 1700] the two worlds, Protestant and Catholic, are consciously separated and consciously antagonistic one to the other. It is a period filled with a great deal of actual physical fighting: "the Religious Wars" in France and in Ireland, above all in the widespread German-speaking regions of Central Europe. A good deal before this physical struggle was over the two adversaries had "crystallized" into permanent form. Catholic Europe had come to accept as apparently inevitable the loss of what are now the Protestant states and cities. Protestant Europe had lost all hope of permanently affecting with its spirit that part of Europe which had been saved for the Faith.

When all this was over [about 1700] there came new developments: the spread of doubt and an anti-Catholic spirit ; while within the Protestant culture, where there was less definite doctrine to challenge, there was less internal division but an increasing general feeling that religious differences must be accepted; a feeling which, in a larger and larger number of individuals, grew into the, at first, secret but later avowed attitude of mind that nothing in religion could be certain, and therefore that toleration of all such opinions was reasonable.

Every strengthening of the now growing national feeling in Christendom made for the weakening of the old religion.By 1517 the nations, especially France and England, were already half conscious of their personalities. They expressed their new patriotism by king- worship. They followed their princes as national leaders even in religion. Meanwhile the popular languages began to separate nations still more as the common Latin of the Church grew less familiar. The whole modern state was developing and the modern economic structure, and all the while geographical discovery and physical and mathematical science were expanding prodigiously.

Hussites in Bohemia: their pretext against the clergy was a demand for the restoration of the cup at Communion to the laity.

All that is lively and effective in the Protestant temper still derives from John Calvin. Though the iron Calvinist affirmations (the core of which was an admission of evil into the Divine nature by the permission of but One Will in the universe) have rusted away, yet his vision of a Moloch God remains; and the coincident Calvinist devotion to material success, the Calvinist antagonism to poverty and humility, survive in full strength. Usury would not be eating up the modern world but for Calvin nor, but for Calvin, would men debase themselves to accept inevitable doom; nor, but for Calvin, would Communism be with us as it is today, nor, but for Calvin, would Scientific Monism [universe without cause] dominate as it (till recently) did the modern world, killing the doctrine of miracle and paralysing Free Will.

The old Catholic Europe, prior to Luther's uprising, had been filled with vast clerical endowments. Rents of land, feudal dues, all manner of incomes, were fixed for the maintenance of bishoprics, cathedral chapters, parish priests, monasteries and nunneries. Not only were there vast incomes, but also endowments (perhaps one- fifth of all the rents of Europe) for every sort of educational establishment, from petty local schools to the great colleges of the universities. There were other endowments for hospitals, others for guilds, (that is, trade unions and associations of craftsmen and merchants and shop- keepers), others for Masses and shrines. All this corporate property was either directly connected with the Catholic Church, or so much part of her patronage as to be under peril of loot wherever the Catholic Church was challenged.

It was this universal robbery of the Church, following upon the religious revolution, which gave the period of conflict the character it had.

It would be a great error to think of the loot of the Church as a mere crime of robbers attacking an innocent victim. The Church endowments had come, before the Reformation, to be treated throughout the greater part of Europe as mere property. Men would buy a clerical income for their sons, or they would make provision for a daughter with a rich nunnery. They would give a bishopric to a boy, purchasing a dispensation for his lack of years. They took the revenues of monasteries wholesale to provide incomes for laymen, putting in a locum tenens to do the work of the abbot, and giving him but a pittance, while the bulk of the endowment was paid for life to the layman who had seized it. Had not these abuses been already universal the subsequent general loot would not have taken place. As things were, it did. What had been temporary invasions of monastic incomes in order to provide temporary wealth for laymen became permanent confiscation wherever the reformation triumphed. Even where bishoprics survived the mass of their income was taken away, and when the whole thing was over you may say that the Church throughout what remained of Catholic Europe, even including Italy and Spain, had not a half of its old revenues left. In that part of Christendom which had broken away, the new Protestant ministers and bishops, the new schools, the new colleges, the new hospitals, enjoyed not a tenth of what the old endowments had yielded.

By the middle of the seventeenth century the religious quarrel in Europe had been at work, most of the time under arms, for over one hundred and thirty years. Men had now settled down to the idea that unity could never be recovered. The economic strength of religion had, in half of Europe, disappeared, and in the other half so shrunk that the lay power was everywhere master. Europe had fallen into two cultures, Catholic and Protestant; these two cultures would always be instinctively and directly opposed one to the other (as they still are), but the directly religious issue was dropping out and, in despair of a common religion, men were concerning themselves more with temporal, above all with dynastic and national, issues, and with the capture of opportunities for increasing wealth by trade rather than with matters of doctrine.

In the Protestant culture (save where it was remote and simple) the free peasant, protected by ancient customs, declined. He died out because the old customs which supported him against the rich were broken up. Rich men acquired the land; great masses of men formerly owning farms became destitute. The modern proletariat began and the seeds of what we today call Capitalism were sown. We can see now what an evil that was, but at the time it meant that the land was better cultivated. New and more scientific methods were more easily applied by the rich landowners of the new Protestant culture than by the Catholic traditional peasantry; and, competition being unchecked, the former triumphed.

Inquiry tended to be more free in the Protestant culture than in the Catholic, because there was no one united authority of doctrine; and though in the long run this was bound to lead to the break-up of philosophy and of all sound thinking, the first effects were stimulating and vitalizing.

But the great, the chief, example of what was happening through the break-up of the old Catholic European unity, was the rise of banking.

Usury was practised everywhere, but in the Catholic culture it was restricted by law and practised with difficulty. In the Protestant culture it became a matter of course. The Protestant merchants of Holland led the way in the beginnings of banking; England followed suit; and that is why the still comparatively small Protestant nations began to acquire formidable economic strength. Their mobile capital and credit kept on increasing compared with their total wealth. The mercantile spirit flourished vigorously among the Dutch and English, and the universal admission of competition continued to favour the growth of the Protestant side of Europe.

These material outward signs of increasing Protestant power and the declining power of the Catholic culture were but the effects of a spiritual thing which was going on within. Faith was breaking down.

The Protestant culture was untroubled by this growth of scepticism. The decline of men's adherence to the old doctrines of Christendom did not weaken Protestant society. The whole tone of mind in that society called every man free to judge for himself, and the one thing it repudiated and would not have was the authority of a common religion.

A common religion is of the nature of the Catholic culture, and so the growing decline of belief worked havoc there. It destroyed the moral authority of the Catholic governments, which were closely associated with religion, and it either cast a sort of paralysis over thought and action, as happened in Spain, or, as happened in France, violently divided men into two camps, clerical and anti-clerical.

For one thing the spiritual basis of Protestantism went to pieces through the breakdown of the Bible as a supreme authority. This breakdown was the result of that very spirit of sceptical inquiry upon which Protestantism had always been based. It had begun by saying, "I deny the authority of the Church: every man must examine the credibility of every doctrine for himself." But it had taken as a prop (illogically enough) the Catholic doctrine of Scriptural inspiration. That great mass of Jewish folklore, poetry and traditional popular history and proverbial wisdom which we call the Old Testament, that body of records of the Early Church which we call the New Testament, the Catholic Church had declared to be Divinely inspired. Protestantism (as we all know) turned this very doctrine of the Church against the Church herself, and appealed to the Bible against Catholic authority.

Hence the Bible_Old and New Testaments combined_became an object of worship in itself throughout the Protestant culture. There was a great deal of doubt and even paganism floating about before the end of the nineteenth century in the nations of Protestant culture; but the mass of their populations, in Germany as in England and Scandinavia, certainly in the United States, anchored themselves to the literal interpretation of the Bible.

Now historical research, research in physical science and research in textual criticism, shook this attitude. The Protestant culture began to go to the other extreme; from having worshipped the very text of the Bible as something immutable and the clear voice of God, it fell to doubting almost everything that the Bible contained.

It questioned the authenticity of the four Gospels, particularly the two written by eye-witnesses to the life of Our Lord and more especially that of St. John, the prime witness to the Incarnation.

It came to deny the historical value of nearly everything in the Old Testament prior to the Babylonian exile; it denied as a matter of course every miracle from cover to cover and every prophecy.

That a document should contain prophecy was taken to prove that it must have been written after the event. Every inconvenient text was labelled as an interpolation. In fine, when this spirit (which was the very product of Protestantism itself) had done with the Bible_the very foundation of Protestantism_it had left nothing of Protestantism but a mass of ruins.

There was also another example of the spirit of Protestantism destroying its own foundations, but in a different field_that of social economics. Protestantism had produced free competition permitting usury and destroying the old safeguards of the small man's property_the guild and the village association.

In most places where it was powerful (and especially in England) Protestantism had destroyed the peasantry altogether. It had produced modern industrialism in its capitalistic form; it had produced modern banking, which at last became the master of the community; but not much more than a lifetime's experience of industrial capitalism and of the banker's usurious power was enough to show that neither the one nor the other could continue. They had bred vast social evils which went from bad to worse, until men, without consciously appreciating the ultimate cause of those evils (which cause is, of course, spiritual and religious) at any rate found the evils unendurable.

There was yet another cause of weakening and decline in the Protestant culture: the various parts of it tended to quarrel one with the other. That was what one would have expected from a system at once based upon competition and flattering human pride. The various Protestant societies, notably the British and Prussian, were each convinced of its own complete superiority. But you cannot have two or more superior races.

This mood of self-worship necessarily led to conflict between the self- worshippers. They might all combine in despising the Catholic culture, but they could not preserve unity among themselves.

The Protestant culture having begun by exaggerating the power of human reason, was ending by abandoning human reason. It boasted its dependence upon instinct and even upon good for- tune. There was no commoner phrase upon the lips of Protestant Englishmen than the phrase, "We are not a logical nation." Each Protestant group was "God's country"_God's favourite_and somehow or other was bound to come out on top without the bother of thinking out a scheme for its own conduct.

Nothing more fatal for an individual or a large society in the long run can be conceived than this blind dependence upon an assured good fortune, and an equally blind neglect of rational processes. It opens the door to every extravagance, material and spiritual; to conceptions of universal dominion, world power and the rest of it, which in their effect are mortal poisons.