Having reviewed the various mainstream models of Biblical chronology for the period of the Divided Monarchy, it is time to take a brief look at the rival models put forward by adherents of the Short Chronology.

As I pointed out in the first article in this series, the Short Chronology involves a radical shortening and realignment of the traditional chronological framework of ancient history. The great civilizations of the Near East—Egyptian, Sumerian (ie Chaldaean), Assyrian, Babylonian, etc—arose after 1500 BCE. Human history—in its current phase, at least—is not nearly as old as we have been taught. This has significant implications for Biblical chronology.

Immanuel Velikovsky, the Father of the Short Chronology, actually accepted the traditional chronology of the Bible—more or less—and shifted the timelines of Israel’s neighbours in order to bring them into alignment with the Scriptures. Since Velikovsky’s death, however, his disciples have taken his pioneering ideas and run with them, creating a radical new chronology of the Ancient World that even Velikovsky might have baulked at. The Bible has not come through this reform unscathed.

But not everything has had to be thrown out. As we shall see, some short chronologists who have tackled the problem of fitting the Hebrew kingdoms into the framework of their new timeline have been quite happy to accept Edwin R Thiele’s internal chronology for this period: they simply propose that Thiele’s model be lifted en bloc out of its current place in the timeline (931-586 BCE) and moved a few centuries closer to our time.

In support of this realignment, they cite a curious gap in Biblical chronology that has been largely ignored—though not overlooked—for centuries.

Emmet J Sweeney

In recent years the Scottish historian Emmet John Sweeney has been one of the foremost proponents of the Short Chronology. His four-volume series Ages in Alignment builds on Velikovsky’s Ages in Chaos. In the final volume of his series, Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Sweeney draws attention to that curious gap in the Biblical record:

It is a fact noted frequently by commentators that the Jews, most assiduous of record-keepers, left not a single document or even note from the time of Ezra (supposedly fifth century BC) until the time of the Maccabees, in the mid-second century BC. Thus, in a period where we should have expected a rich tradition to have survived, there are 250 years of Hebrew history totally unaccounted for. The only Jewish writer to cover the third and fourth centuries is Josephus, but his sources are entirely Hellenistic; and he tells us virtually nothing about the Jews themselves in this epoch. (He does however mention that Alexander came to Jerusalem and honored the Jewish God—rather in the way Cyrus honored the same God). Even worse, Rabbinical Jewish tradition, just like Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus, places the Babylonian Exile and the rebuilding of the Temple in the fourth century (around 350 BC) rather than the sixth. This is a perplexing problem which generations of academics have failed to solve. In fact, there is absolutely no material in the Old Testament to cover the period from the reign of Arta Xerxes I (c.450 BC) and the Seleucid Antiochus Epiphanus (175 BC). Two books, Ezra and Nehemiah, are said to document the period between Cyrus the Great and Arta Xerxes I, but there is nothing afterwards until the First Book of Maccabees, which begins around 175 BC ... It will be immediately obvious that this constitutes a “hiatus” or even a “dark age” comparable to the hiatus observed in Mesopotamian archaeology, where the entire Persian period is missing. (Sweeney 2008:162-163)

Sweeney believes that the Biblical chronology became confused in this era because two different histories were recorded by the Jews: one by the Ten Tribes of Israel and another by the Two Tribes of Judah:

With the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel ... huge numbers of Hebrews were transported eastwards. These persons did not, as many suppose, immediately lose their identity. On the contrary, as the Scriptures themselves make perfectly clear, they continued as a distinct culture and people for many years—surviving indeed until the arrival in exile of their Judaic cousins over a century later. During these years, the exiled Ten Tribes interacted with their Persian conquerors, and some of the books of the Old Testament deal with the fortunes of these exiles under the various Persian Great Kings. However, even as the captive Israelites recorded their fortunes as exiles in Persia and Mesopotamia, the still free people of Judah also continued to keep records—records which told of their struggle for survival against the great power to the east which had already enslaved their Israelite cousins. The chroniclers of Judaic history however called this power and its kings by their Semitic names, whereas the chroniclers of the history of the exiled Israelites, living as they did in the Persian homeland, probably used the Persian names. Thus two parallel histories, one compiled by the free Jews, the other by the exiled Israelites, seem to have developed. When the Scriptures were being written in their final form, during the first century BC, the two distinct traditions were available. Clearly the use of totally different names for the same kings must have caused profound confusion, and eventually the parallel traditions were put in sequence rather than kept as they should have been, contemporary. The misplacement of Persian history also therefore had the effect of throwing Hebrew history into chaos. (Sweeney 2008:162)

Sweeney believes that the fall of Jerusalem and the beginning of the Babylonian Exile occurred around 350 BCE, during the reign of the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes III, who, he claims, was known in Babylon as Nebuchadrezzar. The so-called Neo-Babylonian Emperors are identified by Sweeney with the later Persian Emperors. These have been confused with the similarly named true Neo-Babylonians (or Neo-Chaldaeans), who ruled over southern Mesopotamia between approximately 630 (or 620) and 539 BCE, immediately before the Persians.

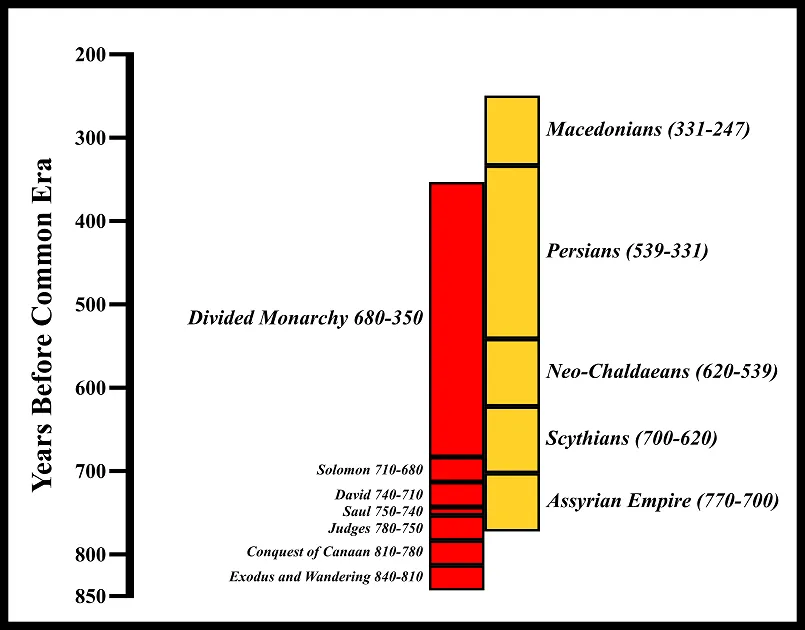

The Divided Monarchy began with the schism between Rehoboam and Jeroboam, which Sweeney relocates to the 7th century. While he accepts Velikovsky realignment of Egyptian and Biblical history in Ages in Chaos, he disagrees with Velikovsky absolute dating of this era:

All that was needed was to move the whole of Ages in Chaos—all the characters and events—lock, stock and barrel a further two centuries or so down the timescale, so that Hatshepsut’s meeting with King Solomon occurred in the early 7th century rather than the latter 10th, whilst Thutmose III’s sacking of Solomon's temple [in the fifth year of Rehoboam] occurred around 675 BC rather than 920 BC. (Sweeney 2006:18)

In Ages in Alignment, Sweeney does not always tie himself down to precise years. If we accept his 675 BCE as the fifth year of Rehoboam, then the Divided Monarchy began in 680 BCE. And if we accept 350 BCE as his date for the fall of Jerusalem, then this period of Jewish history lasted only 330 years. In Thiele’s model, however, the figure is actually 345 years, so Sweeney’s dates may require some tweaking.

Charles Ginenthal

Another champion of the Short Chronology, Charles Ginenthal, has proposed a similar solution to Sweeney’s:

The problem, strictly in terms of the established chronology, is that there is no question that the Old Testament was written in the Persian and Hellenistic epochs, ca. 550-200 B.C., or somewhat later. But the events described by that historical biblical literature in large measure occurred from around 1000 to 500 B.C. It is obvious that the writers of the Bible in Persian-Hellenistic times could not have known in detail the events that transpired so much earlier, and herein lies the dilemma. Furthermore, the very literature of the Bible includes philology as well as material descriptions of that supposedly dead past that also clearly reflect Persian-Hellenistic philological and material elements. It thus appears that these writers projected their own times back into the Israelite past or, most significantly, that the events described occurred in Persian-Hellenistic times. This latter conclusion, namely that the biblical history of many of the kings of Israel after Saul, David and Solomon, occurred in the Persian-Hellenistic epochs, is just what we will show to be the solution to this dilemma. That is, as with all the other chronologies of the ancient world, the chronology of the Bible must also be incorrect and must be moved closer to the present! (Ginenthal 2010:316)

Edwin R Thiele’s success in synchronizing all—well, almost all—the Biblical numbers into one harmonious model is too striking for even a Short Chronologist to dismiss it lightly. And Ginenthal does not dismiss it. Quite the contrary, he accepts it in toto as a valid reflection of the internal relationships between the rulers of Judah and Israel during the period of the Divided Monarchy. He only disputes Thiele’s absolute dating:

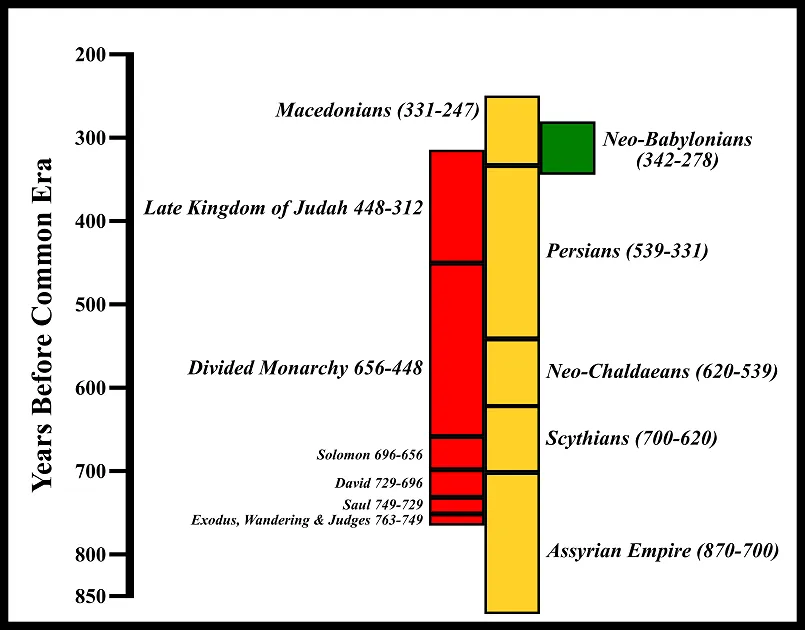

That is, indeed, the historians’ general view of Thiele’s great work. Internally, at least, it seems to be valid, though we suggest the entire history of Israel must be moved en bloc 274 years closer to the present, based on astronomy. (Ginenthal 2010:318)

This precise figure of 274 years is a little larger than Sweeney’s two centuries or so, but is based on astronomical retrocalculations made by Ginenthal’s colleague Professor Lynn E Rose. While Sweeney has the Divided Monarchy beginning around 680 BCE, Ginenthal and Rose place it in 657 or 656 BCE.

A discrepancy of twenty-odd years at the beginning of the Divided Monarchy is, perhaps, no great cause for alarm. At the other end of this era, however, the discrepancy between Sweeney and Ginenthal-Rose is not so easily dismissed. Sweeney has Jerusalem falling to the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes III, whom he identifies with Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon, around 350 BCE. But Ginenthal and Rose’s 274-year lag places this seismic event in 312 BCE, more than ten years after the death of Alexander the Great! This is radical even by the standards of the Short Chronology.

Lynn E Rose

For the most part, Charles Ginenthal has taken his lead in these matters from Professor Lynn E Rose, who used astronomical retrocalculations in support of his chronological reforms. Rose received a BA in Ancient History and Classical Languages (majoring in Greek) from Ohio State University, and was Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the State University of New York in Buffalo. As an advocate of the Short Chronology—a term he introduced and popularized—his major contributions were in the field of archaeoastronomy. In 1999 he published Sun, Moon, and Sothis: A Study of Calendars and Calendar Reforms in Ancient Egypt—essential reading for students of the Short Chronology. He died in 2013.

Lynn Rose was also the author of a long essay, Astronomy and the Short Chronology, which was appended to Volume 4 of Charles Ginenthal’s Pillars of the Past. In this monograph he summarized many of the astronomical retrocalculations that underpin his model of the Short Chronology.

At the outset, Rose acknowledged his debt to other proponents of the Short Chronology, while at the same time distancing himself from certain rival reformers:

Our Short Chronology is not the only radically shortened chronology in the field. The Heraklean labors of Emmet Sweeney and Gunnar Heinsohn, and especially of Immanuel Velikovsky, have taught us much about the radical shortening of ancient chronologies, even though we have come to disagree with all three of them on various details. We also disagree in toto with the very modestly shortened chronologies of David Rohl and Peter James, as well as with the similarly shortened “anno domini” chronology of Heribert Illig and his supporters. Perhaps the very shortest fully-developed chronology that we shall ever see, outside the mind of a solipsist, is that of Anatoly Fomenko. (Ginenthal 2012:593)

Concerning the chronology of the Divided Monarchy, Rose had this to say:

With some caveats, I accept virtually all of Edwin Thiele’s work, especially the durations that he recognizes. As will be explained later, however, I accept Thiele as a relative chronology only. In order to make it absolute, I have to move his whole chronology forward in time by 274 years. (Ginenthal 2012:623-624)

I agree very strongly with Thiele’s overall analysis and reconstruction of Biblical chronology. He deals rather briefly with the United Kingdom of Saul, David, and Solomon, and then in great detail with the Divided Monarchy of Israel and Judah. His chronology seems to me to be brilliant. So far, I have little reason to doubt that it is correct both as a relative or sequential chronology, and also in terms of durations ...

The major respect in which I disagree with Thiele is that his entire chronology fails as an absolute chronology. He tries to make it absolute by linking Biblical events to Assyro-Babylonian events. He takes it as established that Assyro-Babylonian chronology is both absolute and correct ...

As I see it at the moment, Thiele’s chronology not only of the United Kingdom of Saul, David, and Solomon but also of the Divided Monarchy of Israel and Judah is not absolute, but can be rendered absolute, simply by lowering everything by 274 years. Much of Assyro-Babylonian chronology can also be rendered absolute by lowering it by 274 years or thereabouts. There are some places where the required adjustment will vary. This is because the conventional Assyro-Babylonian chronology sometimes does not even have the durations right. (Ginenthal 2012:644-645)

This is neither the time nor the place to investigate the retrocalculations that Rose adduced in support of his model. Many of them can be found in another essay, The Astronomical Evidence for a Shortened Chronology in First-Millennium Mesopotamia, which was appended to Volume 2 of Ginenthal’s Pillars of the Past.

At the conclusion of his monograph, Rose was obliged to acknowledge some of the problems attendant on his model of the Short Chronology. These were particularly acute in connection with the Egyptian pharaohs Apries and Amasis, whom Rose placed after 316 BCE, when the Ptolemaic Macedonians were already the ruling power in Egypt:

We are now getting into the third century. Apries straddles the turn, and Amasis would have reigned entirely in the third century. They must have been vassals, nomarchs, or less. Yet both of them seem to have been already known to Herodotos in the late fifth century! The truth may be that the passages about Apries and Amasis were added long after Herodotos by Alexandrian editors, who edited practically everything, anyway. I once criticized Heinsohn for using such an argument in order to get himself out of difficulty. Having now found myself in a similar difficulty, I retract my criticism of Heinsohn. I hate it when that happens. While I am at it, I must retract my criticism of Rohl for speaking of “The New Chronology”, as if there were only one new chronology. I have in the meantime grown rather fond of speaking of “The Short Chronology”, even though the one that Ginenthal and I favor is but one of many such short chronologies. (Ginenthal 2012:656)

Taking Stock

Of the two models of the Short Chronology that I have considered in this article, I am currently more inclined to accept Sweeney’s. Treating Nebuchadnezzar II as a subordinate of Seleucus I Nicator is a bridge too far for me. And Rose’s need to revise Herodotus is a red flag.

But what, then, is one to do with all the retrocalculations that supposedly led Rose to this pass? Some Short Chronologists—Gunnar Heinsohn, for example—simply reject archaeoastronomy out of hand. Others—Sweeney seems to fall into this camp—don’t trust it as an accurate guide to the past.

At the other end of things, Sweeney places the rise of the Assyrian Empire after the Exodus, whereas Rose-Ginenthal synchronize the Exodus with the Assyrians’ retreat from Egypt (recorded by the Egyptians as the Expulsion of the Hyksos). At this end of the story, I side with Rose and Ginenthal.

Above is a rough outline of Sweeney’s chronology for Babylonia, aligned with his Biblical chronology. For comparison, here is a similarly rough outline of the Rose-Ginenthal model for the same period, with Thiele’s Biblical chronology adjusted to match:

To be continued ...

References

- Charles Ginenthal, Mesopotamian, Anatolian, Mycenaean, Minoan, and Harappan Chronology, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, New York (2008)

- Charles Ginenthal, Egypt and Palestine, Pillars of the Past, Volume 3, Forest Hills, New York (2010)

- Charles Ginenthal, Chronology of the Age of Stonehenge and the Megalithic World, Pillars of the Past, Volume 4, Forest Hills, New York (2012)

- Lynn E Rose, Sun, Moon, and Sothis: A Study of Calendars and Calendar Reforms in Ancient Egypt, KRONOS Press, Deerfield Beach Fl (1999)

- Emmet John Sweeney, Empire of Thebes, or Ages In Chaos Revisited, Ages in Alignment, Volume 3, Algora Publishing, New York (2006)

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

- Edwin R Thiele, The Chronology of the Kings of Judah and Israel, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Volume 3, Number 3 (July 1944), pp 137-186, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1944)

- Edwin R Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, Third Edition, Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids MI (1983)

Image Credits

- Possible depiction of Jehu King of Israel giving tribute to King Shalmaneser III of Assyria: Wikimedia Commons, © Stephen G Johnson, Creative Commons License

- Nehemiah Viewing the Ruined Walls of Jerusalem: Wikimedia Commons, Gustave Doré (artist), Public Domain

- Emmet J Sweeney: © Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (SIS), Fair Use

- Edwin R Thiele: © Andrews University, Fair Use

- Charles Ginenthal: © Dwardu Cardona, Fair Use

- Lynn E Rose: © The Velikovsky Encyclopedia, Fair Use

- Babylonian and Jewish Short Chronology (After Sweeney): Self-Made, Kopimi

- Babylonian and Jewish Short Chronology (After Rose, Ginenthal and Thiele): Self-made, Kopimi