What happens when you are called upon to illustrate a book requiring extensive research because it is both fiction and historical at the same time? A rush of excitement.

It means research and time travel. It also justifies my overflowing library of costume reference books.

It's a challenge to uncover the mystery of period costume and all it entails. What can I get away with, and what will be noticed by other perfectionists like me? At times like this, I'd give anything to be a textile conservator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, or even the Smithsonian.

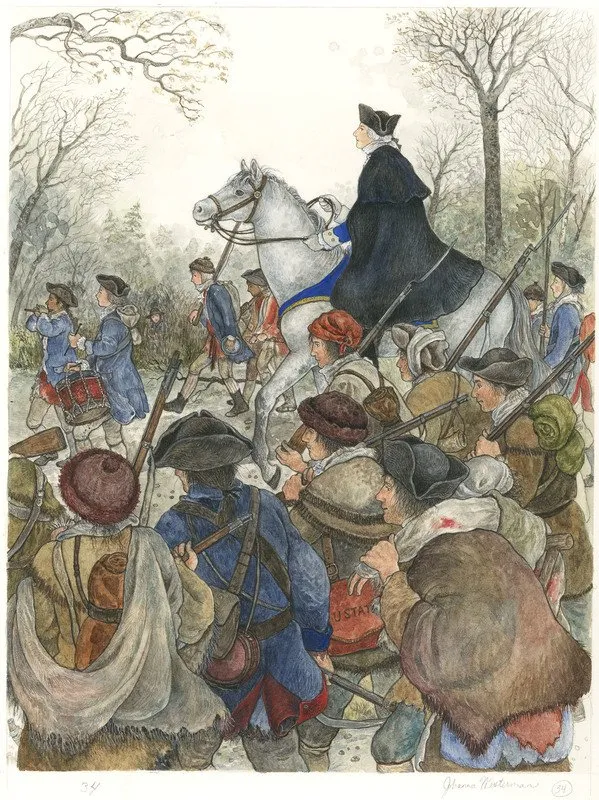

This project involved the Revolutionary War. It was a fictional story mixed in with real events including George Washington himself. Having been married to the head archivist at Mount Vernon proved to be a big advantage. I already had a built-in knowledge of the time period, as well as an established familiarity with our first president.

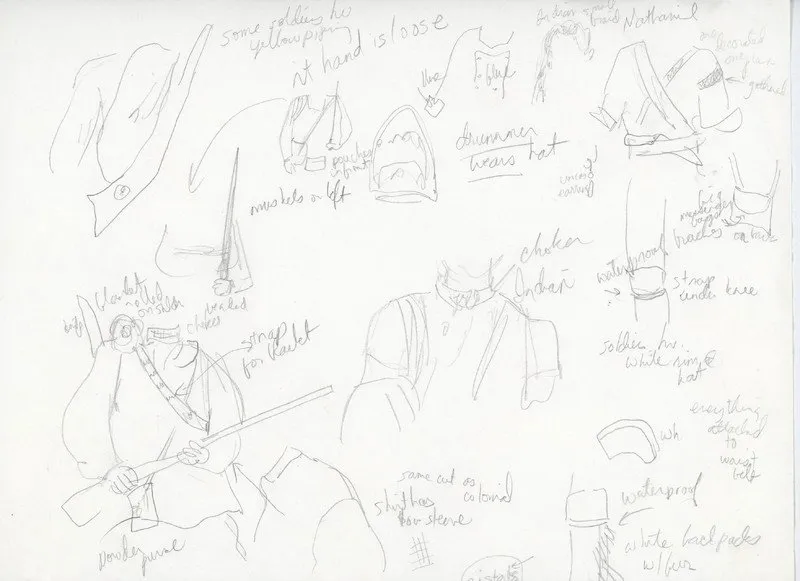

I began a flurry of sketches.

How do I make the costumes believable? By stripping back the layers to really understand the structure of clothing, naturally. What was decoration, and what was functional? It was important for me to understand how garments were sewn. How did they fasten? What were undergarments composed of?

I found some of my reference materials in unlikely places. The movie Last of the Mohicans was an invaluable resource.

Not that it was too difficult to watch the movie, pausing it as needed to sketch Nathaniel and Uncas in their frontier garb. By watching movies, I understand better the overall functionality of clothing and how it can help or hinder movement. The French and Indian War may have taken place 20 years earlier, but it was close enough that clothing had not changed much.

This rough page of sketches helps me make the mental connection of how figures move in the clothes they wear. This was not an era of Gore-Tex and other high tech waterproof materials. Things must have been pretty uncomfortable all around. I imagined the blisters inflicted by the friction of wet leather. Maybe that would be the least of your troubles. How about being barefoot in the snow?

I wanted to highlight the effect the freezing temperatures had on the soldiers more than the bravery of the Delaware crossing.

I had to get into the time period of my characters and ask questions. "Why?" and "How?" were the two biggest ones. For example, if you were an American soldier, what would be the most efficient way to lug all your gear around? What made sense and why? Everything would have to be easily accessible. There was also the question of placement. Where were weapons carried, and how about gunpowder? As a soldier, you were probably a farmer or working class citizen arriving to fight ill-prepared and ill-equipped to withstand the elements.

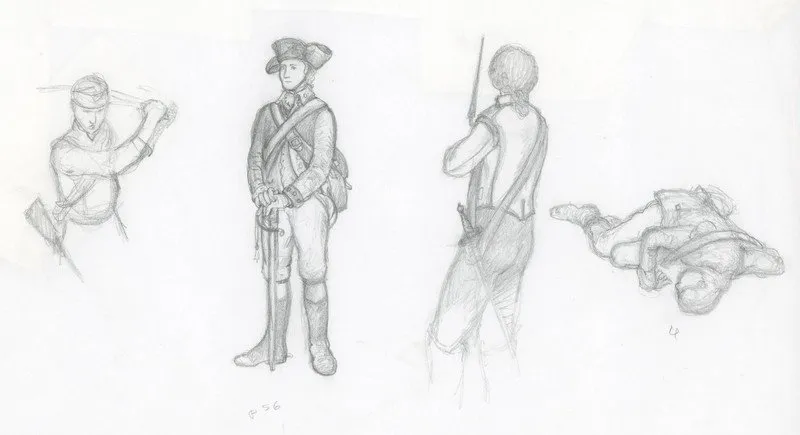

initial rough layout sketches become

this more finished state

The reason these look like clippings is because they were. When I compose my illustrations, sometimes it's easier to pick them up like puzzle pieces and arrange them into a scene.

You can see how I inserted the figure studies into the finished painting.

When illustrating an educational book, I thought accuracy and attention to this kind of detail would be high on the list of priorities for schools as well.

I was wrong.

I learned something new. When depicting a grisly battle scene, one may portray muskets....minus the bayonets. I was told to eliminate them from my illustrations, because bayonets are too violent. I am not one to exaggerate violence in my work. But I do not believe we do anyone, children in particular, a service by sanitizing the horrors of war. Bayonets were used. War is horrible. Muskets were used to kill people, and bayonets were as well. You can bet the resulting battles were nothing less than indescribable bloodbaths from all the stabbing.

They were fine with bloodstained clothing and injured soldiers. (And an edit - bayonets were fine to show if they weren't being used in a battle scene.)

Now for an interesting side note. Originally, I intended to share my sketches and how they developed into a finished book. I didn't set out to take a political direction with my illustration post, but found it somehow evolved into a bit of a rant. I am angry, and here is one of the many reasons why.

During our recent trip to England, our friends introduced us to an interesting chap who happened to have been a writer for history text books. And the quest for authenticity has been censored more than you can imagine. For the American market, not only was he told to omit many truths of this country and its founding, he was actively "encouraged" to change the outcomes of many events to put the USA in a more favorable light. Was I surprised? Sadly, no. This sinister undertone is to keep us unaware of real historical events with the premise of teaching our kids only what they want us to know. Our high school kids are reading fiction, not historically accurate facts.

As much as I enjoyed working on this book, it was a sobering realization that we are not teaching history the way it really happened. I could be as accurate as possible with the way people dressed. But when it comes to the real horrors of war, it's best to play it down.

If you think about it, isn't that what our country is great at doing these days? Creating distractions while government-created atrocities wipe out thousands of innocent women and children every day?

Whatever you do, don't show bayonets to children.

How ironic that illustrating an educational picture book portraying the victories of our first president had to be censored for violence.

That is something to think about.

Illustrations ©Johanna Westerman 2016

Movie still, Last of the Mohicans, 20th Century Fox, 1992