The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology.

In this article we will continue our study of Part 2 of Heinsohn’s lecture: The sequence of ancient empires with the center in Assyria as it was taught by Greek historians since the time of Hekateios (-560/550 to -500/494).. Here Heinsohn is concerned with Upper Mesopotamia—the region centred on the River Tigris and known to Classical historians as Assyria.

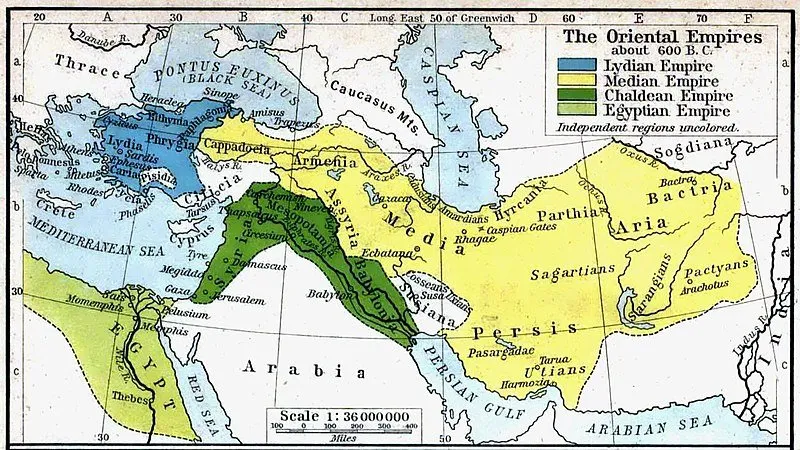

Based on these accounts, Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Assyria before Alexander the Great:

- 1150-750: Early Assyrians

- 750-620: Assyrian Empire

- 620-540: Empire of the Medes

- 540-330: Persian Empire

In the two preceding articles, we looked at the history of Assyria as recorded by the Classical historians Herodotus and Ctesias, who provided the models on which later historians based their accounts. We learnt that the Classical historians were in broad agreement that Assyria had once formed the nucleus of three successive empires—Assyrian, Median, and Persian—prior to the conquests of Alexander the Great. There may also have been a brief period during the Empire of the Medes when the Scythians were the dominant nation in Mesopotamia. In this article, we are going to see whether the archaeology of the region supports these accounts.

The Elusive Medes

The short answer to this question is No:

In the 1980’s, a series of eight major conferences brought together the world’s finest experts on the history of the Medish and Persian empires. They reached startling results. The empire of Ninos ... was not even mentioned. Yet, its Medish successors were extensively dealt with—to no great avail. In 1988, one of the organizers of the eight conferences, stated the simple absence of an empire of the Medes ... : “A Median oral tradition as a source for Herodotus III 95106 is a hypothesis that solves some problems, but has otherwise little to recommend it ... This means that not even in Herodotus’ Median history a real empire is safely attested. In Assyrian and Babylonian records and in the archeological evidence no vestiges of an imperial structure can be found. The very existence of a Median empire, with the emphasis on empire, is thus questionable” (H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, Was There Ever a Median Empire?, in A. Kuhrt, H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, eds., Achaemenid History III: Method and Theory, Leiden, 1988, p. 212). (Heinsohn, Part 2)

Why would Herodotus, Ctesias and all of their successors assert the existence of an Empire of the Medes if no such empire ever existed? Diodorus Siculus even describes it as the mighty empire of the Medes, so we are not talking about a minor kingdom (Oldfather 457).

In the following years, the “elusiveness” of the mighty Empire of the Medes became a byword among Assyriologists. In 1994, Christopher Tuplin of the University of Liverpool repeated it, noting:

... the general archaeological and historical elusiveness of the Medes. (Tuplin 1994:251)

In 2004, Tuplin returned to the Medish problem and hypothesized that for a brief period they enjoyed domination but not hegemony or empire:

One has a stronger sense of the seizure of power because a power-vacuum presented itself and to do so suited a cultural taste—one relatively newly emerged and therefore particularly energising—for military self-expression than of the assertion and pursuit of a supposed shared agenda. Rather than hegemony, therefore, let us perhaps speak of ‘domination’. Above all, let us reaffirm the importance of the Median interlude in creating conditions from which other Iranians—heirs both to the Scytho-Median and to a more Mesopotamian (and literate) state-model—would create the largest empire (properly so-called) the Near Eastern and Western worlds had yet seen. (Tuplin 2004:242-243)

Charles Ginenthal

One of Gunnar Heinsohn’s most assiduous adherents, Charles Ginenthal, has also researched this perplexing discrepancy between the history of Assyria as recorded by the Classical historians and the history of Assyria as deduced by modern historians. Since Heinsohn’s lecture in 1994, things have not improved. The Empire of the Medes remains elusive:

To overcome this Median Dark Age problem, a conference was held to bring together the leading researchers in the field of Median studies, at Padua in Italy on the 26th through the 28th of April 2001. The volume of these proceedings, discussed in part above, titled Continuity of Empire (?), was published in 2003. Rather than this convocation coming close to unraveling this Median Dark Age, there was shock at its conclusion when it was realized that practically no headway could be made in resolving the dilemma. (Ginenthal 323)

Ginenthal cites extensively the Assyriologist James D Muhly, who reviewed the proceedings of this conference:

I believe it is fair to say that, prior to the conference, no participant had any inkling of just how difficult it would be to ‘pin down’ the Medes. The degree of exasperation this situation produced is evident in the tone of many of the published texts. Michael Roaf, for example, has concluded that ‘This survey of the evidence, both textual and archaeological for Media between 612 and 550 BC, has revealed almost nothing. Media in the first half of the sixth century [B.C.] is a Dark Age’ (p. 19). John Curtis laments that ‘It has to be admitted at the outset that there is not the slightest archaeological indication of a Median presence in Assyria after 612 BC (p. 165) and this of course is the very period for which the Medes were supposed to have provided ‘continuity’ [between the Neo Assyrians and Persians].

What about the Median state that we have always assumed, following Herodotus and the Babylonian Chronicle, played the central role in the destruction of the [Neo-]Assyrian empire at the end of the seventh century BC? David Stronach, who certainly knows more about the Medes than any other living scholar, states early on in his essay, that ‘it may be enough to assert that there are, quite simply, no sound grounds for postulating the existence of a vigorous, separate and united Median kingdom, at any date substantially before 615 BC’ (p. 234). (Muhly 4)

This problem is exacerbated by the suspicion that many objects catalogued in museums as of Median provenance are probably not Median at all. As Muhly notes:

Can this problem be approached in other ways? In 1962 Richard Barnett, then Keeper of Western Asiatic Antiquities at the British Museum, published an article on “Median Art”, bringing together all the objects that he felt represented the material culture of the ancient Medes. In a 1987 article on “Median Art and Medizing Scholarship” Oscar White Muscarella demonstrated that not one of the objects listed by Barnett had an excavated context. They all came from the antiquities market and were of questionable authenticity. They were declared ‘Median’ simply because they did not seem to belong to the art of Achaemenid Persia. They could not be assigned a secure cultural and historical context and must, therefore, represent the art of the elusive Medes.

Nothing could better illustrate the “Black Hole” that this conference tried so hard to fill (with a notable lack of success). It has come to be the fate of the Medes, in terms of art and iconography, to be represented by objects illicitly excavated and therefore of questionable authenticity. This problem has come to the fore, once again, because of a flood of objects that came on the art market in the 1990’s, all said to come from a cave in western Iran, the ‘Western’ Cave or the Kalmakarra Cave (see Souren Melikian, “Cultural Ecology: Saving the Past, Debate Rages over Antiquities,” International Herald Tribune 10-11 January 1998, p. 7). It soon became obvious that many pieces said to be from this cave were, in fact, modern forgeries. What is even more disturbing is that a number of ‘Cave’ objects were inscribed with short epigraphs in cuneiform, in Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Elamite as well as alphabetic inscriptions in Aramaic. This material is dealt with in some detail by Wouter Henkelman in his contribution to this conference volume. (Muhly 4-5)

The archaeology of the Empire of the Medes is simply missing:

... the Medes—left us but scanty archeological evidence. (Oppenheim 69)

But things were about to get worse for modern Assyriologists:

The Elusive Persians

According to Herodotus, Mesopotamia—embracing both Assyria and Babylonia—was the wealthiest satrapy in the entire Persian Empire:

There are many proofs of the wealth of Babylon, but this in especial. All the land ruled by the great King is parcelled out for the provisioning of himself and his army, besides that it pays tribute: now the territory of Babylon feeds him for four out of the twelve months in the year, the whole of the rest of Asia providing for the other eight. Thus the wealth of Assyria is one third of the whole wealth of Asia. The governorship, which the Persians call ‘satrapy,’ of this land is by far the greatest of all the governorships. (Godley 241, Herodotus 1:192)

But once again the archaeological evidence for this huge wealth is thin on the ground:

Two years later came the really bewildering revelation. Humankind’s first world empire of the Persians ... did not fare much better than the Medes. Its imperial dimensions had dryly to be labeled “elusive” (H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, The Quest for an Elusive Empire?, in H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, A. Kuhrt, eds., Achaemenid History IV: Centre and Periphery, Leiden 1990, p. 264). (Heinsohn, Part 2)

To mislay one of the Ancient World’s mighty empires is careless : to mislay two of them is downright criminal.

Sancisi-Weerdenburg summed up the discrepancy between the archaeology and the recorded history of the Persian Empire thus:

The extant evidence seems to allow one to argue both for a monolithic empire as well as an amalgam of culturally distinct and politically semi-independent areas. The former position is founded on generalisations based on material from regions for which documentation is available. The second conclusion is generally derived from archaeological evidence. This situation is clearly unsatisfactory. Unless we are prepared to settle for two divergent views of the empire, an ‘archaeological’ one and a ‘historical’ one, an attempt must be made to integrate the divergent evidence into a synthesis. (Sancisi-Weerdenburg 263)

In the same conference, one of Sancisi-Weerdenburg’s colleagues gave the following assessment of the archaeological evidence for Achaemenid Assyria:

Yet the region of Assyria immediately to the north (centered around the modern Iraqi cities of Mosul and Erbil) and the northwest lying on and within the Euphrates (now part of the modern state of Syria) was in earlier periods closely intertwined, culturally and politically, with Babylonia. Further it formed part of the Persian administrative region of Babylonia (cf. Leuze 1935) certainly from the reign of Xerxes on (Böhl 1962; Graf 1985) if not slightly earlier (Leuze 1935; Kuhrt 1988a: 131), yet artefacts, texts and excavated sites that can be dated to the Achaemenid period (or, indeed the Neo-Babylonian one—for exceptions cf. Gadd 1958 (Harran); Curtis 1989 (north Assyria)) are extremely sparse, making it difficult to present even a sketchy picture of this enormous and crucially important area. (Kuhrt 177)

But Upper Mesopotamia was not unique in this regard. Even in Babylon itself, the presence of the Imperial Achaemenids is elusive—as we shall see in the next article.

To be continued ...

References

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, NY (2003)

- Alfred Denis Godley (translator), Herodotus, Volume 1, The Histories, Books 1-2, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1920)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Amélie Kuhrt, Achaemenid Babylonia: Sources and Problems, Achaemenid History: 4: Centre and Periphery, pp 177-194, Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, Leiden (1990)

- David D Muhly, Review of Continuity of Empire (?), Bryn Mawr Classical Review, Bryn Mawr College/University of Pennsylvania, Bryn Mawr, PA (2004)

- C H Oldfather, Diodorus of Sicily, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1946)

- A Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization, Revised Edition Completed by Erica Reiner, University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1977)

- Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, The Quest for an Elusive Empire, Achaemenid History: 4: Centre and Periphery, pp 263-274, Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, Leiden (1990)

- Christopher Tuplin, Persian as Medes, Achaemenid History: 8: Continuity and Change, pp 223-251, Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, Leiden (1994)

- Christopher Tuplin, Medes in Media, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia: Empire, Hegemony, Domination or Illusion?, Ancient West and East, Volume 3, Number 2, pp 223-251, Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden (2004)

Image Credits

- Interior of an Assyrian Palace Restored (After Layard): George Rawlinson, The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, Volume 1, John W Lovell Company, New York (1880), Public Domain

- The Empire of the Medes: William Robert Shepherd, The Historical Atlas, p 8, The Colonial Offset Co, Inc, Pikesville, MD (1923), Public Domain

- Charles Ginenthal: © Dwardu Cardona, Creative Commons License

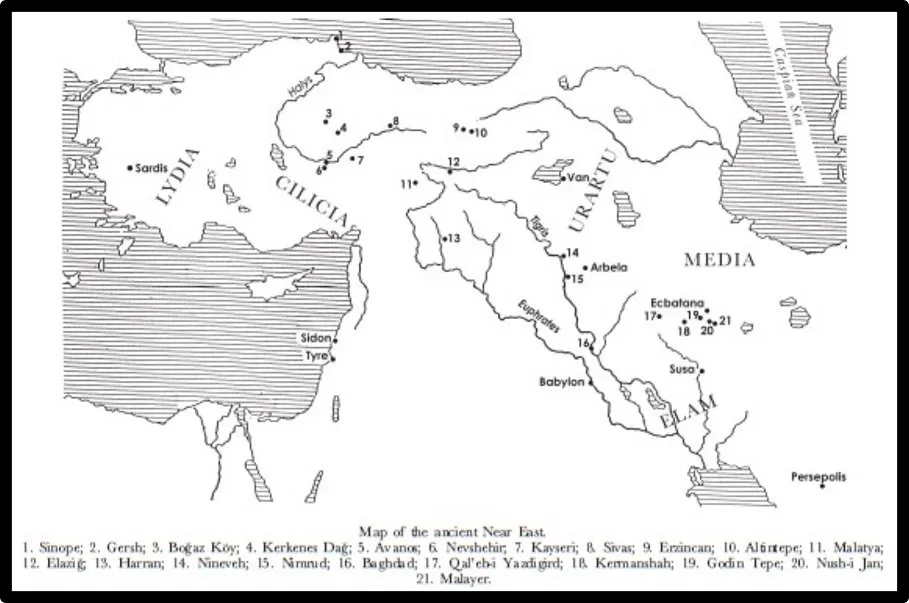

- The Ancient East: © Christopher Tuplin, Fair Use

- Silver Griffin Rhyton from the Kalmakarra Cave: US Department of State, Public Domain

- Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg: © Shahr Baraz, Creative Commons License

Online Resources