The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology:

Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Mesopotamia before the conquests of Alexander the Great:

| Dates BCE | Assyria | Babylonia |

|---|---|---|

| 1150-750 | Early Assyrians | Early Chaldaeans |

| 750-620 | Assyrian Empire | Assyrian Empire and Scythians |

| 620-540 | Empire of the Medes | Chaldaeans |

| 540-330 | Persian Empire | Persian Empire |

In this article we will continue our survey of Part 3 of Heinsohn’s lecture: Archaeologically-missing history and historically-unexpected archaeology in major areas of antiquity.. In this section, Heinsohn reviews a long list of cases where archaeologists have discovered major discrepancies between the archaeology of the Ancient World and its history as recorded by the Classical historians. These discrepancies fall into two broad categories:

Excavations in which the archaeologists failed to find strata that the recorded history had led them to expect.

Excavations in which the archaeologists uncovered strata that did not correspond to any cultures or civilizations in the recorded history.

Heinsohn noticed that many of these discrepancies came in matching pairs. In the last article we met one such pair: the Chaldaeans and the Sumerians. In this article we will examine another: the Medes and the Mitannians:

(2) Rule of Indo-Aryan speaking Mitanni in Assyria (-1500 to -1350)

(2) Rule of Indo-Aryan speaking Medes in Assyria ca. -630 (Heinsohn)

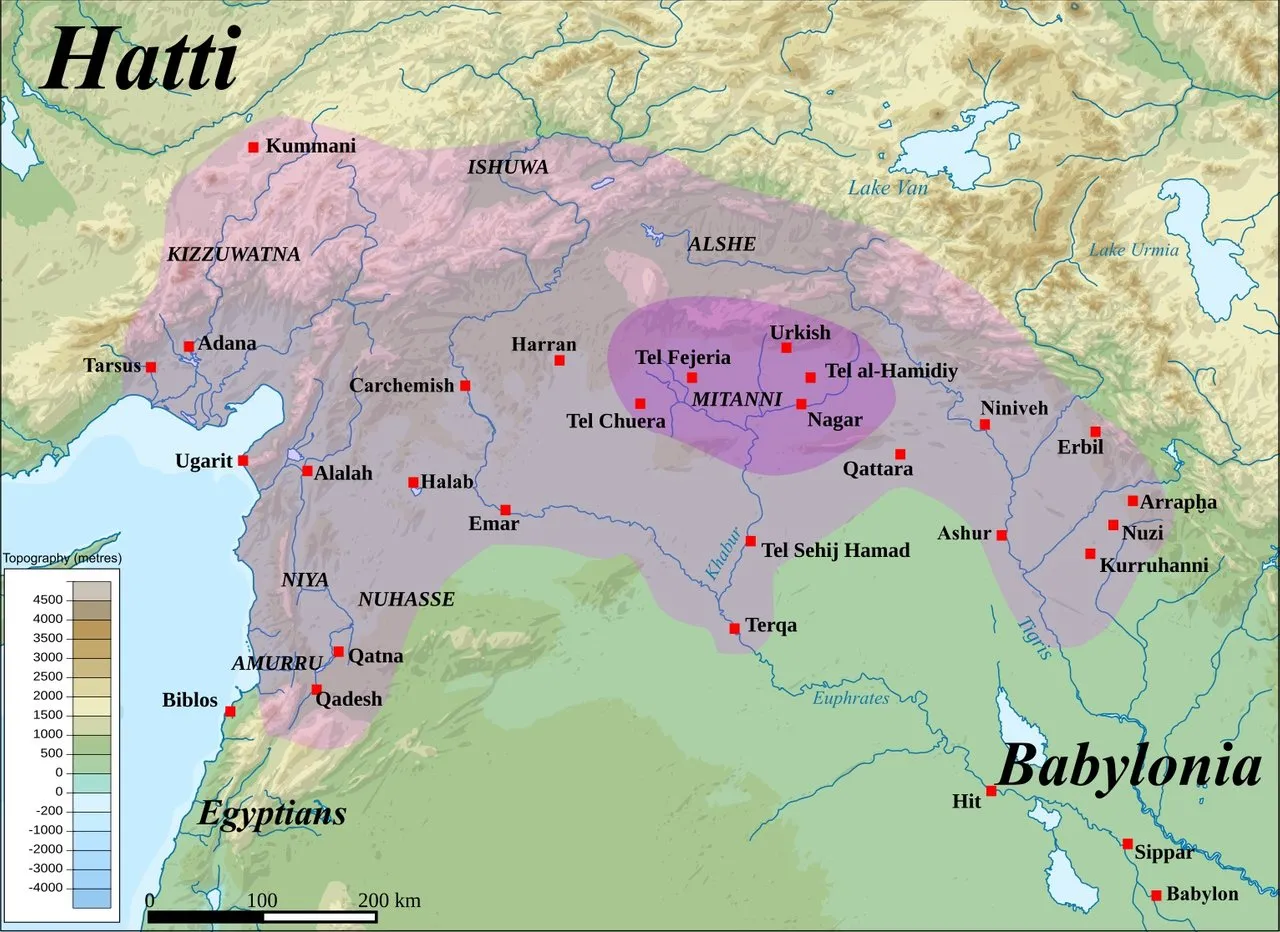

Mitanni was an ancient state of Upper Mesopotamia. (Heinsohn makes the common mistake of also referring to the inhabitants of this state as Mitanni.) According to the conventional chronology, it existed from around 1500 BCE till 1260 BCE, which places it between the Old and Middle Assyrian Empires. The rulers of Mitanni bore Indo-Aryan names, but the vernacular of the subject people appears to have been Hurrian. Mitanni was ruled by a succession of about fourteen kings, before it was finally extinguished by the Middle Assyrian Emperor Shalmaneser I.

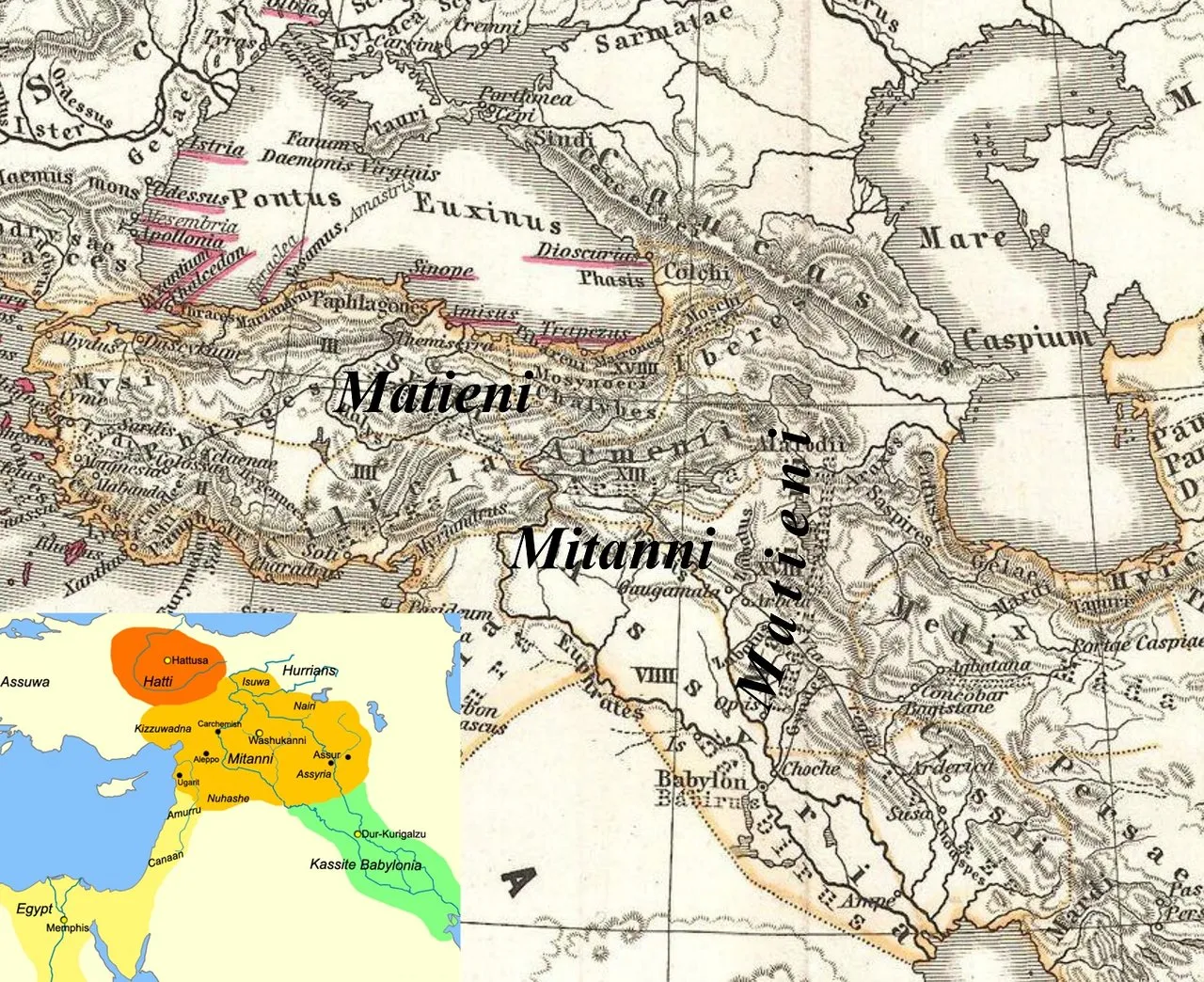

All of this has been deduced from archaeological excavations. Assyrian records in particular have been revealing, as Mitanni itself has left relatively little material of an archival nature. Furthermore, the Classical historians knew nothing of Mitanni. Herodotus never mentions any such kingdom, though he does refer on a few occasions to the Matieni, a people who appear to have dwelt both to the east and to the west of the Tigris (Godley 89, 237, 255).

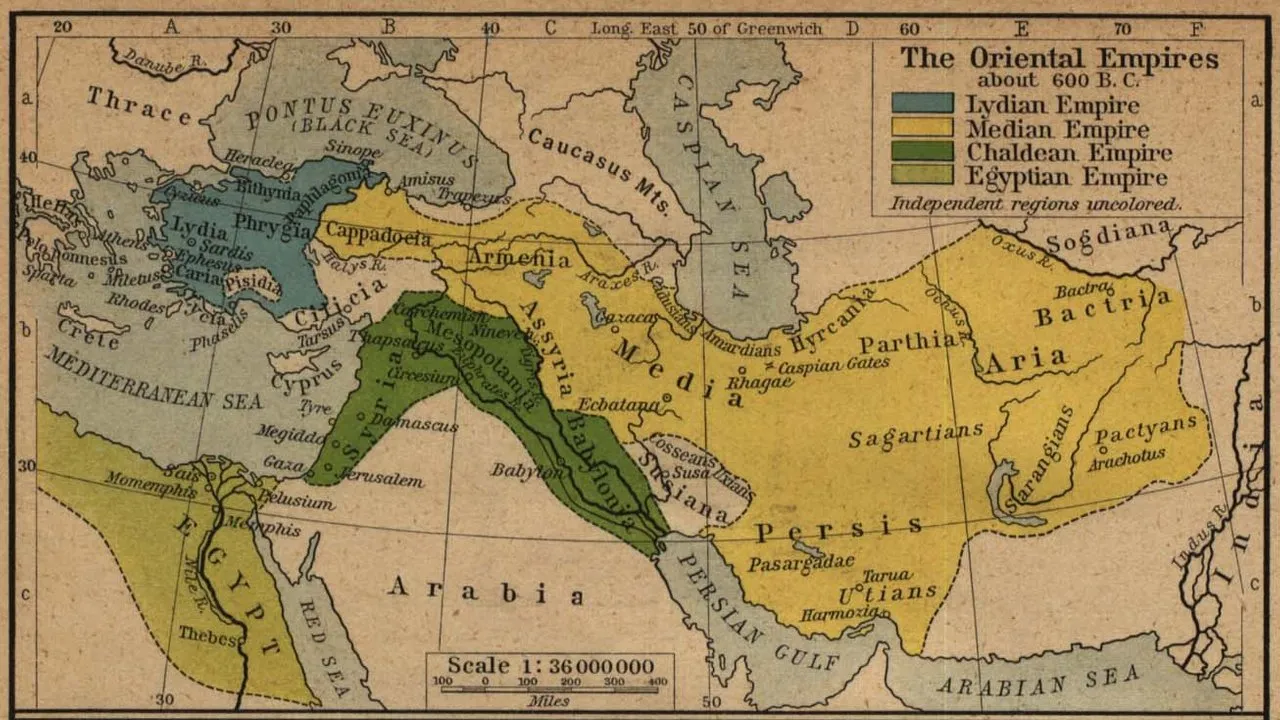

Medes

In an earlier article in this series, we saw how modern scholars have described the Empire of the Medes as “elusive” (Sancisi-Weerdenburg 263-274). The archaeology of the Medes is simply missing, leading modern historians to doubt the veracity of their ancient counterparts. This not only applies to monuments and cities, but also to written records:

... no Median written documents of any kind have ever been uncovered ... (Adler 744)

This is an extraordinary state of affairs for a mighty empire, but the very same thing can be said of Mitanni:

No native sources for the history of Mitanni have been found so far. The account is mainly based on Assyrian, Hittite, and Egyptian sources, as well as inscriptions from nearby places in Syria. (Wikipedia)

Although they are generally recognized as having an important place in the history of the ancient Near East, the Medes have left no textual source to reconstruct their history, which is known only from outside sources such as the Assyrians, Babylonians and Greeks, as well as a few Iranian archaeological sites, which are believed to have been occupied by Medes. (Wikipedia)

Heinsohn drew the same conclusion that Immanuel Velikovsky had drawn a few decades earlier: the Kingdom of Mitanni and the Empire of the Medes were one and the same:

We assume that the Mitanni was the original name of the Medes ... (Velikovsky 179)

Tell Munbāqa

In 1993 Heinsohn drew the scholarly world’s attention to the stratigraphy of Tell Munbāqa, or Mumbaqat, a site in northern Syria, which has been identified with the ruins of the ancient city of Ekalte. This tell was discovered in 1907 by the English explorers William M Ramsay and Gertrude Bell, and excavated over a period of almost forty years. Since 1979, the excavations have been directed by Dittmar Machule of the Technical University of Hamburg at Harburg. These excavations revealed that the site had been occupied during the Early Bronze Age (which included the Akkadian Empire) and the Late Bronze Age (Mitanni), but initially no evidence was found for occupation of the site during the intervening Middle Bronze Age (Middle Assyrian Empire).

According to the conventional chronology, the stratigraphy ought to have included an appreciable stratum of aeolian—wind-blown—sediments, which would have accumulated during the 600 years that the site was unoccupied. But this expected stratum of aeolian material was absent. Dittmar’s archaeological team called in Ulrike Rösner of the University of Erlangen, an expert in the field of sedimentation, to assess their findings:

The second complex of problems in 1989, the year of the investigations, referred to the question, if there was a Middle Bronze Age occupation on Tall Munbāqa at all and if it was so, what could it have been like. “The Middle Bronze Age left a specific kind of pottery, which is distinctly proven by architecture on other ruins, but which is only sparse in Munbāqa and occurs only at certain locations. The problem is ... that levels with definite Early Bronze Age ceramics are followed directly by levels with definite Late Bronze Age ceramics” (D. Machule, written, translated communication). The question was asked whether there was a hiatus, i.e. a longer lasting interruption of the occupation. (Rösner 208)

But Rösner only confirmed the discrepancy:

The analyses of the sediments directly above the oldest Late Bronze Age road level (H2) point to a fire in that city district. After that the area was exposed for estimated 50 to 75 years and covered by wind blown sediments. Due to a relatively fast burying by broken down wall remainders the aeolian sediment character was preserved. In 1989, the year of the investigation, the excavators discussed an occupation gap between the Early and the Late Bronze Age. However, no sedimentological indications for a Middle Bronze Age occupation gap were discovered ...

The part of the profile concerning the question of the Middle Bronze Age occupation is horizon 11 (sample 102/14). Up to here the ceramic finds can definitely be dated back to the Early Bronze Age (approx. 3000-2100 y BC). Above that the ceramic finds prove a Late Bronze Age occupation (approx. 1500- 1200 y BC). However, the zone in question in between the Early and the Late Bronze Age sediment complexes did not contain any definite archaeological proof for a Middle Bronze Age occupation at the time when the investigations were carried out ... The time period under question (approx. 2100-1500 y BC) is climatically coinciding with the one in which—after palynological results—the present semiarid conditions in the Near East had already been reached (see Bottema 1989, 6) and in which the requirements for an aeolian dynamic had already been given. Even though the dimensions of the wind erosion and transport in the steppe regions are strongly depending on the intensity of the land use (ploughing, herding) in the surroundings (see Rösner 1989; Rösner and Schäbitz 1991), there should be at least some evidence for aeolian activity in the referred horizon, considering the time range of about 600 years of possible absence of occupation on the mound. In any case the fluvial deposits are available as provenance areas of fine material during the dry seasons of the year at a low watertable. But the sample 102/14 does not bear signs of aeolian dynamic ... Furthermore some calculations concerning the sediment thickness seem to be informative: within the time period between the beginning of the Late Bronze Age (approx. 1500 y BC) and today 180 cm of sediment grew up. This is an average rate of 0,05 cm a year. At a duration of the possible occupation gap of 600 years a sediment body of 30 cm were to be expected. But the horizon 11 has only a thickness of 15 cm. It is surely a risk to use rates of sedimentation on settlement places. But the difference between the actual thickness and the one to be expected is very considerable especially taking into account the results of the sediment examination above the Late Bronze Age road level: an aeolian component is here already proved for a shorter time period of absence of occupation, estimated 50 to 75 years. Summarizing all these considerations, there is no evidence at all from a sedimentological point of view for an occupation gap during the Middle Bronze Age. (Rösner 217 ... 218)

Rösner concluded her analysis with the following remarks:

Detailed study of the sediments from Tall Munbāqa along with evaluation of archaeological findings yielded evidence to events having taken place during the occupation as well as to chronological problems.

Indications of a fire followed by aeolian covering were found in the sediments above a road level of the first Late Bronze Age period. The range of time during which the devasted area was lying bare can roughly be assumed with 50 to 75 years.

The accurate investigation of a cultural level, which should theoretically represent a Middle Bronze Age occupation gap, could not prove an aeolian component. But to be certain it would have to be expected at an actual interruption of the occupation of about 600 years. This Statement is sustained by the results of the sediment analyses above the oldest Late Bronze Age road. Therefore, including the first archaeological results, it is more likely that a continuous occupation has existed. Later on, these sedimentological interpretations were confirmed by new archaeological findings on Tall Munbāqa made during the excavations of the early nineties (see D. Machule 1995). (Rösner 218)

In 1997, the results of the archaeological excavations at Tell Munbāqa were published in Volume 8 of the Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie in an article penned by Machule himself:

§ 2. Settlement History: The foundation is dated to the latter part of the Early Bronze Age (EB III/IV). A few isolated Ubaid potsherds reached well with mudbricks in the ruins. In the Middle Bronze Age, it appears that only the northwestern part of M[unbāqa] was settled. The heyday [of the town] lay at the start of the Late Bronze Age (three major phases of settlement with several strata of destruction and rebuilding). In Roman and Byzantine times M[unbāqa] served as a necropolis. In the Islamic Era few indications of settlement are to be found ...

§2.2. Middle Bronze Age: In the northwestern corner a temple complex with a domestic wing and a substantial inventory was unearthed (multi-stepped niches for idols, thresholds, pedestals and also simple geometric wall paintings).

This temple complex was all that was found from a period that is said to have lasted 600 years. In his analysis of the subject, Charles Ginenthal even calls into question the dating of this temple to the Middle Bronze Age, suspecting that its presence has been exploited to try and fill the embarrassing gap in the stratigraphy:

Also, why would there be a large Middle Bronze Age temple in one area, if there isn’t a township nearby to serve it? Where would the worshippers for the gods have come from? The entire elaborate ad hoc thesis invented to create a settlement gap where none exists makes no sense under any considerations! (Ginenthal 1:257)

The actual stratigraphy at Tell Munbāqa vindicates Heinsohn’s Short Chronology, which identifies the Early Bronze Age with the Assyrian Empire and the Late Bronze Age with the Empire of the Medes, with no substantial hiatus or gap between the two:

| Strata | Era | Conventional Dates | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 182 cm | Late Bronze Age | 1500-1260 | 240 years |

| 16 cm | Middle Bronze Age | 2100-1500 | 600 years |

| 176 cm | Early Bronze Age | 3000-2100 | 900 years |

Twenty-five years later, however, mainstream archaeologists continue to uphold their exploded chronology. They are so wedded to this framework that not even facts are permitted to undermine it.

Similarities and Dissimilarities

There are many intriguing similarities between the Medes and the Mitannians, but there also a few undeniable dissimilarities:

| - | Media | Mitanni |

|---|---|---|

| Kings | Indo-Aryan | Indo-Aryan |

| Gods | Indo-Aryan | Indo-Aryan |

| Native Records | None | None |

| Origins | East of the Zagros | East of the Zagros |

| Capital | Washukanni | Ecbatana |

| Heartland | East of the Zagros | West of the Zagros |

Critics of Heinsohn’s—and Velikovsky’s—hypothesis have highlighted two discrepancies in particular:

The heartland of Media is generally placed to the east of the Zagros Mountains, whereas Mitanni was centred in northern Mesopotamia, to the west of the Zagros.

The capital city of the Medes was Ecbatana, which lies in the eastern foothills of the Zagros Mountains at Hamadan, whereas the capital city of Mitanni was Washukanni, whose location has been determined by archaeologists to be on the headwaters of the Khabur River far to the west of the Zagros—about 800 km from Hamadan.

The short answer to these criticisms is quite simple: If the Empire of the Medes is elusive, if the archaeology of Media is missing, and if the Medes left no written records of their own, then how can one be sure where the heartland of Media was or where the capital city was located? It can also be pointed out that Herodotus’s Matieni dwelt in two distinct regions on either side of the Zagros Mountains: one of these lay close to Mitanni (Godley 89), while the other lay in Media (Godley 237, 255).

A longer answer, however, is in order.

Washukanni and Ecbatana

The locations of these two cities are not known with anything approaching certainty. Ecbatana is generally identified with the modern town of Hamadan in Iran, but this identification has been contested. In his article on Ecbatana in the Encyclopædia Iranica, however, Stuart C Brown asserts that the identification is now beyond dispute:

On both historical and archeological grounds, the identification of Ecbatana with Hamadān is secure (Bücher; Frye, 1979; Hüsing; Weissbach). However, the scarcity of visible pre-Islamic remains led some early European visitors to suggest alternative locations such as Susa (Chardin, III, p. 15), Kangāvar (Ferrier, p. 32), and Taḵt-e Solaymān (Rawlinson). (Brown 80-84)

But this scarcity of Median remains has persisted to the present day:

Relatively few finds thus far can be firmly dated to the Median era. (Wikipedia)

§ 1. Excavation and Discoveries: Unfortunately, the Median capital has hardly been revealed to archaeologists through excavations, as these have been thwarted by the presence of the modern city, which occupies the same place as the ancient city; the only scientific excavation was undertaken in 1913 by Fossey, and his report has never been published. (Edzard 4:64)

To my mind, such a state of affairs hardly justifies the use of the word “secure”.

There are also some discrepancies among the Classical sources. According to Herodotus, Ecbatana was a walled city:

But having obtained the power, [Deioces] constrained the Medes to make him one stronghold and to fortify this more strongly than all the rest. This too the Medes did for him: so he built the great and mighty circles of walls within walls which are now called Agbatana. This fortress is so planned that each circle of walls is higher than the next outer circle by no more than the height of its battlements; to which end the site itself, being on a hill in the plain, somewhat helps, but chiefly it was accomplished by art There are seven circles in all; within the innermost circle are the king’s dwellings and the treasuries; and the longest wall is about the length of the wall that surrounds the city of Athens. The battlements of the first circle are white, of the second black, of the third circle purple, of the fourth blue, and of the fifth orange: thus the battlements of five circles are painted with colours; and the battlements of the last two circles are coated, these with silver and those with gold. (Godley 129-130)

But according to another Classical historian, Polybius, Ecbatana was unwalled:

27. In regard to extent of territory Media is the most considerable of the kingdoms in Asia, as also in respect of the number and excellent qualities of its men, and not less so of its horses. For, in fact, it supplies nearly all Asia with these animals, the royal studs being entrusted to the Medes because of the rich pastures in their country. To protect it from the neighbouring barbarians a ring of Greek cities was built round it by the orders of Alexander. The chief exception to this is Ecbatana, which stands on the north of Media, in the district of Asia bordering on the Maeotis and Euxine. It was originally the royal city of the Medes, and vastly superior to the other cities in wealth and the splendour of its buildings. It is situated on the skirts of Mount Orontes, and is without walls, though containing an artificially formed citadel fortified to an astonishing strength. (Shuckburgh 25-26)

It could be argued that Herodotus is describing the walls around Polybius’s fortified citadel and not the city itself. Note, also, that Polybius describes the location of Ecbatana as bordering on the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea—hardly an accurate description of the location of Hamadan. He also places it on the skirts of Mount Orontes. The latter is identified with a peak in the Zagros Mountains close to Hamadan, but the better known Orontes River rises in Lebanon and discharges into the Mediterranean Sea in Syria, on the other side of the Zagros. Diodorus of Siculus, however, clearly places Ecbatana in the eastern Zagros (Oldfather 391-397).

The location of Washukanni is even more uncertain. The leading candidate is Tell el-Fakhariya, an ancient site in the Khabur River basin of northern Syria, but this has been contested by several scholars (Brown 80-84).

In Sanskrit, which is thought to have been the native language of the Mitannian ruling class, the original form of the name was possibly Vasukhani. This is not particularly close to Ecbatana. The latter, which is a Hellenistic name for the place, is only one of several variants:

- Ἐκβάτανα (Ecbatana

- Hagmatāna or Haŋmatāna

- Agmadana

- Ahmadān

- Aḥmeta

- Ἀγβάτανα (Agbatana)

- Agamtanu

In classical and other sources the name variously occurs: Gk: Ekbátana, Agbátana (the reading Apobátana in Isidore of Charax, 6, should be Agbátana), Lt. Ecbatana, Ecbatanas, Ecbatanis Partiorum (Tabula Peutingeriana), bibl. Aram. Aḥmeta, Arm. Aḥmatan, Hamatan, Ekbatan, Mid. Pers. Hamadān, etc. (Weissbach, col. 2155; Ezra 6.2). (Brown 80-84)

None of these is particularly close to Vasukhani, while several are very close to the modern Hamadan.

On the other hand, there were at least seven ancient cities called Ecbatana, so even if the modern city of Hamadan covers the ruins of an ancient city called Ecbatana, this may not have been the Median capital of that name (Brown 80-84).

Emmet Sweeney has suggested that Ecbatana may be a corruption of Washukanni:

The capital of Mitanni is generally given as Washukanni, or Washuganni; though, since cuneiform vowels are conjectural, the name could equally be reconstructed as Awshakanna, or Ebshakanna. Furthermore, since in many languages the sounds ‘sh’ and ‘t’ are frequently confused ... the name could even be reconstructed as Ebtakanna. The capital of the Medes, rendered Ecbatana by the Hellenic authors, is apparently little more than a [hypocorism] ... of this word. (Sweeney, Ramessides, Medes and Persians, The Velikovskian, Volume 5, Number 2 (2001))

I can’t say that I find any of this terribly convincing. In my opinion, it would be better to argue that while Vasukhani was the Sanskrit name the ruling Mitannians gave to the city, Ecbatana (or one of its variants) was an unrelated native name. Several of the variants of Ecbatana contain an element—-matāna, -madana, -madān, -amtanu—which could be echoes of Mitanni. At least one scholar has suggested that the name is from the Elamite *hal.mata.na, meaning “Land of the Medes” (Brown 80-84). The Nabonidus Chronicle also refers to Ecbatana as a “country” rather than a city (Lendering).

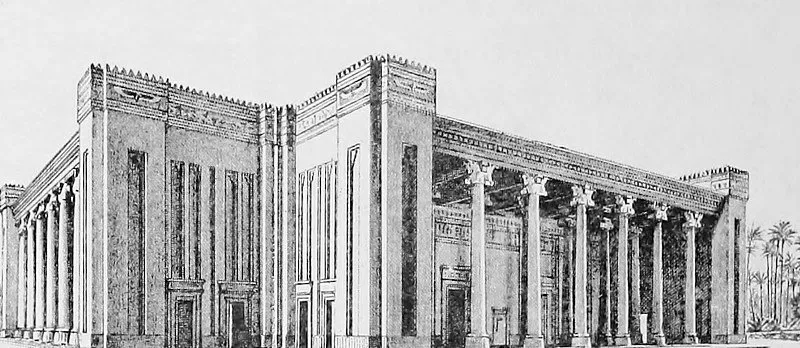

Could Ecbatana be connected with the Old Persian apadana, a hypostyle hall, ie a palace or audience hall of stone construction with columns? There was an apadana at Ecbatana, though it may have been constructed by one of the Persian Emperors (Nichols 16 fn 28). Apadana is also a word in Sanskrit, which was allegedly the language of the Mitannian ruling class.

Parting Comments

My own hypothesis is that the Medes or Mitannians were migrants from the Indus-Valley Civilization, who moved westwards into Mesopotamia around 700 BCE (Short Chronology), when the Indus-Valley Civilization collapsed due to climate change and the salinization of the land. Other Indo-Aryans migrated eastwards into India, where they established the Vedic civilization. The ruling class of Mitanni are believed to have spoken a form of Sanskrit. The names of their gods and their kings were certainly Sanskrit, as is clear from two treaties between Hatti and Mitanni, which were discovered in Hattusas, the Hattian capital.

In conclusion, there are grounds for accepting the hypothesis that Mitanni and the Empire of the Medes were one and the same, but this hypothesis is still beset by a number of significant difficulties—most notably that of reconciling the locations of Ecbatana and Washukanni.

But this is a good place to stop.

To be continued ...

References

- Mortimer Jerome Adler (principal editor), Encyclopædia Britannica, Fifteenth Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, Chicago, Il (1975)

- Stuart C Brown, Ecbatana, Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume 8, Fascicle 1, pp 80–84, Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation, Columbia University, New York (1997)

- Dietz Otto Edzard (editor), Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie, Volume 4, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin (1972-1975)

- Dietz Otto Edzard (editor), Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie, Volume 8, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin (1997)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 1, Forest Hills, NY (2003)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, NY (2003)

- Alfred Denis Godley (translator), Herodotus, Volume 1, The Histories, Books 1-2, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1920)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Dittmar Machule, Felix Blocher, Excavations at Tall Munbāqa/Ekalte (Province of Raqqa) 1999-2010, Seminar for Oriental Archaeology and Art History, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (2012)

- Andrew Nichols, The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus: Translation and Commentary with an Introduction, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL (2008)

- C H Oldfather, Diodorus of Sicily, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1946)

- Ulrike Rösner, Sedimentological Evidences to Archaeological Problems on Tall Munbāqa, Northsyria, Quartär, Band 45/46, pp 207-219, Hugo Obermaier Society for Ice Age and Stone Age Research, Erlangen (1995)

- Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, The Quest for an Elusive Empire, Achaemenid History: 4: Centre and Periphery, pp 263-274, Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, Leiden (1986)

- Evelyn S Shuckburgh, The Histories of Polybius, Translated from the Text of F Hultsch, Volume 2, Macmillan and Co, London (1889)

- Emmet J Sweeney, Ramessides, Medes and Persians, The Velikovskian, Volume 5, Number 2, Forest Hills (2001)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Ramses II and His Time, Ages in Chaos, Volume 4, Doubleday and Company, New York (1978)

Image Credits

- Tell Munbāqa: © Tall Munbāqa Mission, Fair Use

- Map of Mitanni: Adapted, © Zunkir, Creative Commons License

- The Empire of the Medes: The University of Texas at Austin, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, William Robert Shepherd, The Historical Atlas, Public Domain

- The Sanctuary at Tell Munbāqa: © Tall Munbāqa Mission, Fair Use

- The Sanctuary Area at Tell Munbāqa: © Tall Munbāqa Mission, Fair Use

- The Soil Profile of Tell Munbāqa: © Ulrike Rösner, Sedimentological Evidences to Archaeological Problems on Tall Munbāqa, Northsyria, Figure 6, Profile Munbāqa, Fair Use

- Mitanni and the Matieni of Herodotus: Karl Spruner von Merz (artist), Public Domain, Mitanni Inset Javierfv1212 (creator), Public Domain

- Ecbatana: © Ninara, Creative Commons License

- Tell el-Fakhariya: © Sebastian Hageneuer, Creative Commons License

- The Apadana at Susa: Gaston Maspero, Archibald Henry Sayce, History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, Volume 9, p 270, Grolier Society, London (1903), Public Domain

Online Resources