The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology.

In this article we will begin our study of Part 2 of Heinsohn’s lecture: The sequence of ancient empires with the center in Assyria as it was taught by Greek historians since the time of Hekateios (-560/550 to -500/494)..

Assyrians, Medes, Persians

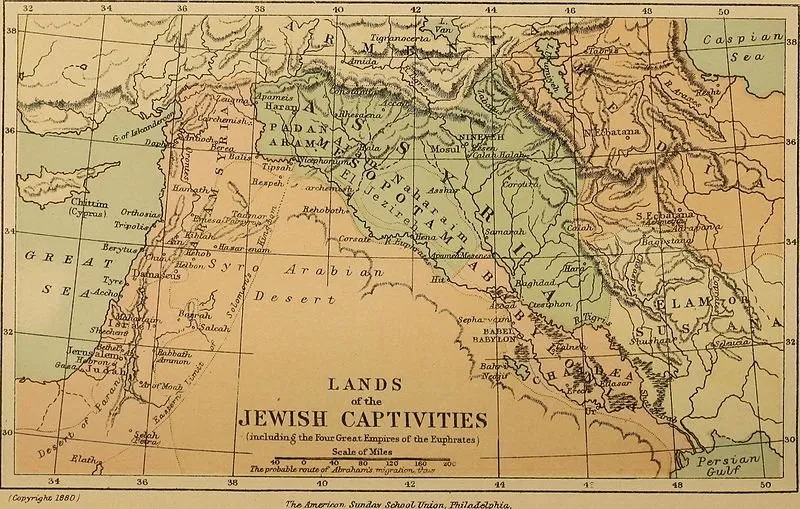

In this part of his lecture, Heinsohn is concerned with Upper Mesopotamia—the region centred on the River Tigris known to Classical historians as Assyria. He points out that the Classical historians were in broad agreement that this area had once been the nucleus of three successive empires—those of the Assyrians, the Medes, and the Persians—prior to the conquests of Alexander the Great.

Based on these accounts, Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Assyria before Alexander the Great:

| Dates BCE | Period |

|---|---|

| 1150-750 | Early Assyrians |

| 750-620 | Assyrian Empire |

| 620-540 | Empire of the Medes |

| 540-330 | Persian Empire |

The Classical historians knew of only one Assyrian Empire. This is in stark contrast to the opinion of modern historians, who recognize three: the Old Assyrian Empire, the Middle Assyrian Empire, and the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Let us see what the Classical sources actually say.

Hecataeus

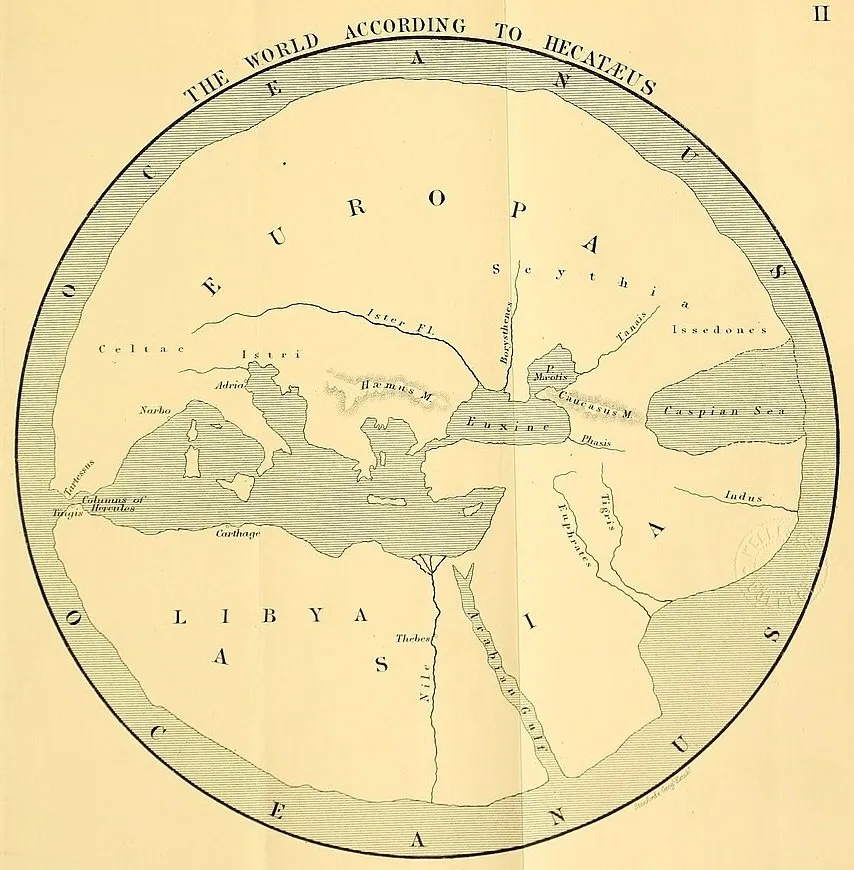

Hecataeus of Miletus is the earliest Greek historian of whom anything is known. He lived a couple of generations before Herodotus, who was clearly indebted to him. It is possible that he was still alive when Herodotus was a young boy. Heinsohn gives his dates as -560/550 to -500/494. The former is in accord with most online sources, but according to the 10th-century Byzantine encyclopaedia Suda, Hecataeus was born during the reign of Darius the Great (522-486) in the 65th Olympiad (520-517). There is also much uncertainty concerning the year of his death, with estimates ranging from 500 to 476.

Of his Genealogies or Histories there survive only 40 fragments. Of his other known work, Tour Round the World, more than 300 fragments survive. Although the latter is primarily concerned with the geography of the Mediterranean world, it also touches upon the histories of the Scythians, Persians, Indians, Egyptians, and Nubians. Hecataeus is believed to have travelled extensively in the Persian Empire, but none of the surviving fragments of his work tells us anything of note concerning the history of Assyria:

One writer who traveled extensively in the Persian Empire, including possibly Mesopotamia, was Hecataeus of Miletus (circa 500 B.C.E.). Unfortunately, it remains uncertain that he included anything about either Assyria or Babylonia in his two works, the Periegesis and the Genealogiai, both now lost. This is a pity, as it is known from a reference in Herodotus that Hecataeus tried, in his work on genealogies, to question the Greek view of early history by showing that the generations of Greek heroes reached back only a few hundred years, as opposed to the thousands of years found among some eastern peoples. (Jeremiah Genest)

So Hecataeus, like Heinsohn, was skeptical of the received chronology.

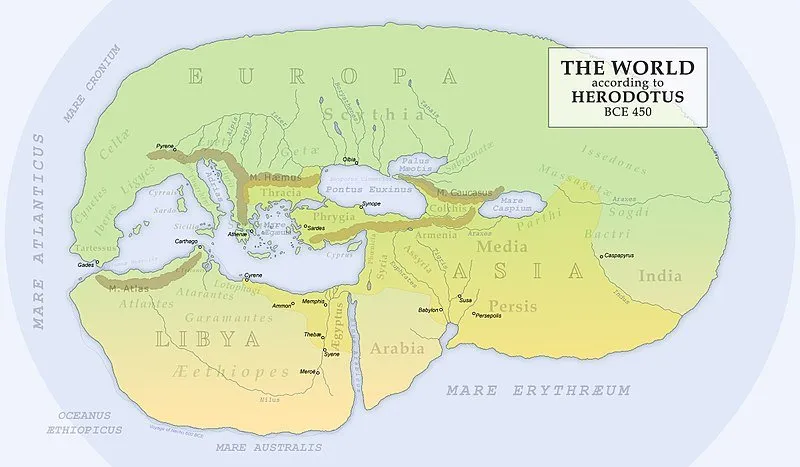

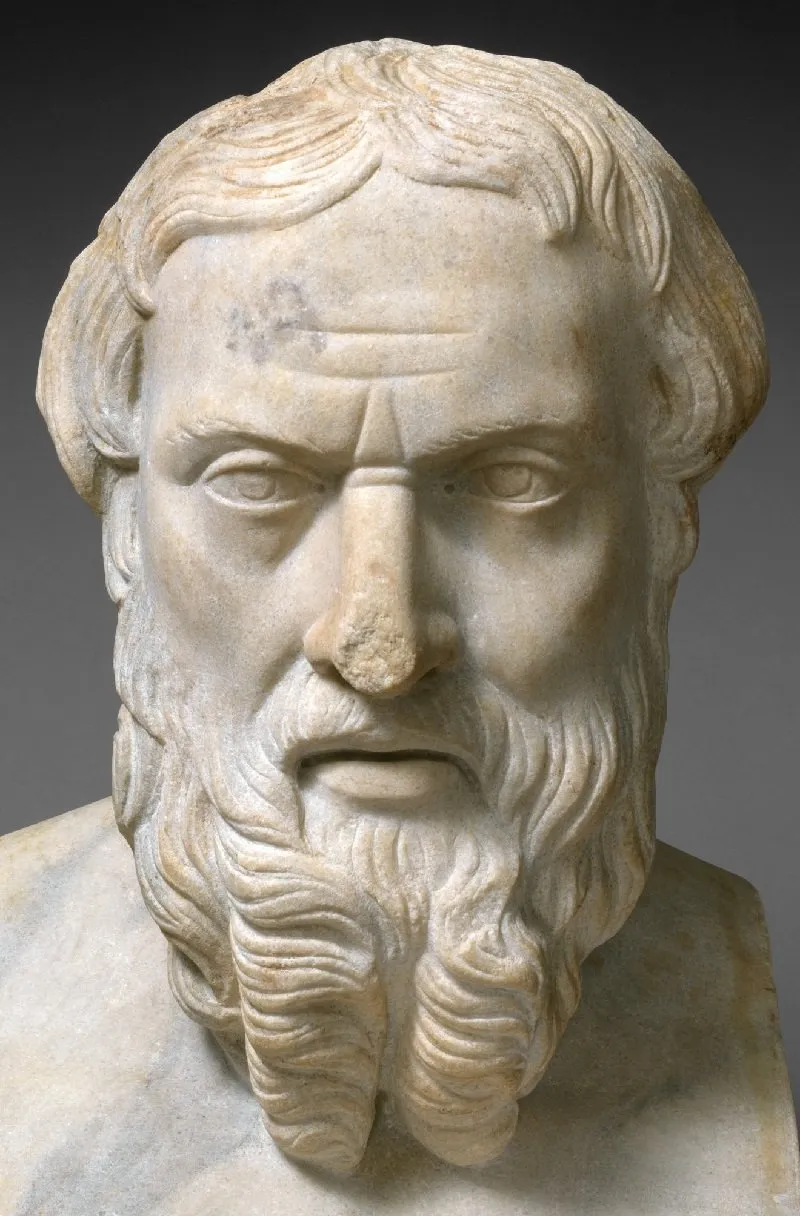

Herodotus

Heinsohn’s next historian, Herodotus, is a frustrating source for the early history of Assyria. His extensive Histories have survived and have earned him the title of Father of History (Cicero)—though he is often also referred to as the Father of Lies—but his account of Assyrian history is deficient:

In his travels Herodotus had heard much about the Assyrians, and had promised to write of them (I, 184). But his Assyrian logoi never materialized, and the information which he did pass on to his public was scattered and sparse. He spoke of Assyria as a nation which had ruled Asia for 520 years, its hegemony being inherited by the Medes (I, 95). A low interpretation of Herodotus’ chronological references would place this Assyrian hegemony at 1219-699 B.C. He mentioned Ninus, Semiramis, Sennacherib and Sardanapalus without attempting to fix the succession of Assyrian monarchs. (Drews 129-130)

In the introduction to his 1954 translation of the Histories, Aubrey de Sélincourt expresses similar frustration:

There are in fact just three famous unfulfilled promises ... I, 106, on how the Medes took Nineveh ... The loss of the ‘Assyrian story’ on the other hand is a great pity. Our author and traveller must have had many interesting things to say, and (surely?) notes ... Powell believes that he suppressed the Assyrian history, as being simply too long, and such as to unbalance the narrative; but this surely is not like our author as he reveals himself, with his concern that what he knew about ‘the great deeds of men’ should ‘not be forgotten’. (Sélincourt 19-20)

If Herodotus had written his Assyrian History, he could only have taken the story down to -430 or so, when the Histories were completed. What we do learn of Assyrian history in the pages of Herodotus can be summarized quite briefly:

1:95 ... When the Assyrians had ruled Upper Asia for five hundred and twenty years their subjects began to revolt from them ...

2:141 ... So presently came king Sanacharib against Egypt, with a great host of Arabians and Assyrians ... [Sethos King of Egypt] encamped at Pelusium with such Egyptians as would follow him, for here is the road into Egypt ... Their enemies too came thither, and one night a multitude of fieldmice swarmed over the Assyrian camp and devoured their quivers and their bows and the handles of their shields likewise, insomuch that they fled the next day unarmed and many fell ...

2:150. ... I had heard of a like thing happening in the Assyrian city of Ninus. Sardanapallus king of Ninus had great wealth, which he kept in an underground treasury. Certain thieves were minded to carry it off; they reckoned their course and dug an underground way from their own house to the palace, carrying the earth taken out of the dug passage at night to the Tigris, which runs past Ninus, till at length they accomplished their desire.

1:95 ... When the Assyrians had ruled Upper Asia for five hundred and twenty years their subjects began to revolt from them: first of all, the Medes. These, it would seem, proved their valour in fighting for freedom against the Assyrians; they cast off their slavery and won freedom. Afterwards the other subject nations too did the same as the Medes.

1:96. All of those on the mainland were now free men; but they came once more to be ruled by monarchs as I will now relate ...

1:101. Deioces, then, united the Median nation, and no other, and ruled it ...

1:102. Deioces had a son, Phraortes, who inherited the throne at Deioces’ death after a reign of fifty-three years. Having so inherited, he was not content to rule the Medes alone: marching against the Persians, he attacked them first, and they were the first whom he made subject to the Medes. Then, with these two strong nations at his back, he subdued one nation of Asia after another, till he marched against the Assyrians, to wit, those of the Assyrians who held Ninus. These had formerly been rulers of all ; but now their allies had dropped from them and they were left alone, yet in themselves a prosperous people: marching then against these Assyrians, Phraortes himself and the greater part of his army perished, after he had reigned twenty-two years.

1:103. At his death he was succeeded by his son Cyaxares. He is said to have been a much greater warrior than his fathers ... This was the king who fought against the Lydians when the day was turned to night in the battle, and who united under his dominion all Asia that is beyond the river Halys. Collecting all his subjects, he marched against Ninus, wishing to avenge his father and to destroy the city. He defeated the Assyrians in battle; but while he was besieging their city there came down upon him a great army of Scythians, led by their king Madyes son of Protothyes ...

1:104 ... There the Medes met the Scythians, who worsted them in battle and deprived them of their rule, and made themselves masters of all Asia ...

1:106. The Scythians, then, ruled Asia for twenty-eight years: and all the land was wasted by reason of their violence and their pride ... The greater number of them were entertained and made drunk and then slain by Cyaxares and the Medes: so thus the Medes won back their empire and all that they had formerly possessed; and they took Ninus (in what manner I will show in a later part of my history), and brought all Assyria except the province of Babylon under their rule.

1:107. Afterwards Cyaxares died after a reign of forty years (among which I count the years of the Scythian domination): and his son Astyages reigned in his stead ...

1:130. Thus Astyages was deposed from his sovereignty after a reign of thirty-five years: and the Medians were made to bow down before the Persians by reason of Astyages’ cruelty. They had ruled all Asia beyond the Halys for one hundred and twenty-eight years, from which must be taken the time when the Scythians held sway ...

1:184. Now among the many rulers of this city of Babylon (of whom I shall make mention in my Assyrian history), who finished the building of the walls and the temples, there were two that were women. The first of these lived five generations earlier than the second, and her name was Semiramis ...

1:185. The second queen, whose name was Nitocris, was a wiser woman than the first. She left such monuments as I shall record; and moreover, seeing that the rulers of Media were powerful and unresting, insomuch that Ninus itself among other cities had fallen before them, she took such care as she could for her protection ...

1:178. When Cyrus had brought all the mainland under his sway, he attacked the Assyrians. There are in Assyria many other great cities; but the most famous and the strongest was Babylon, where the royal dwelling had been set after the destruction of Ninus ...

1:214 ... There perished the greater part of the Persian army, and there fell Cyrus himself, having reigned thirty years in all save one.

3:67. Cambyses being dead, the Magian, pretending to be the Smerdis of like name, Cyrus’ son, reigned without fear for the seven months lacking to Cambyses’ full eight years of kingship ...

7:4. Having declared Xerxes king, Darius was intent on his expedition. But in the year after this, and the revolt of Egypt, death came upon him in the midst of his preparation, after a reign of six and thirty years in all ...

7:7. Having been over-persuaded to send an expedition against Hellas, Xerxes first marched against the [Egyptian] rebels, in the year after Darius’ death ...

7:20. For full four years from the conquest of Egypt he was equipping his host and preparing all that was needful therefor; and ere the fifth year was completed he set forth on his march with the might of a great multitude ...

8:51. Now after the crossing of the Hellespont whence they began their march, the foreigners had spent one month in their passage into Europe, and in three more months they arrived in Attica, Calliades being then archon at Athens. There they took the city, then left desolate ...

(Godley 127 et passim)

Note that Herodotus recognizes a short period of Scythian domination that interrupted the Empire of the Medes for 28 years. And he always refers to the city of Nineveh as Ninus [Νινος].

Herodotus’ chronology can be reconstructed thus:

In the year after his accession to the Persian throne, Xerxes suppressed a rebellion in Egypt.

Xerxes spent the following four years preparing for the invasion of Greece.

The following year Xerxes launched his invasion of Greece. In the fall, his army occupied Athens, which the Athenians had abandoned. Herodotus tells us explicitly that this occurred during the archonship of Calliades, which lasted from July 480 through June 479 BCE. These dates are well attested and seem reliable (Samuel 206-210). The occupation of Athens by the Persian army, therefore, took place in -480.

Therefore, Darius died and Xerxes acceded to the throne in -486.

Darius I reigned for 36 years: 522-486.

Cambyses’ reign and the short reign of Smerdis lasted 8 years: 530-522.

Cyrus reigned for 29 years: 559-530.

The Medes reigned for 128 years (including a period of 28 years when the Scythians were the dominant regime in Mesopotamia): 687-559

The Assyrians were dominant for 520 years before the rise of the Medes: 1207-687.

The reign-lengths which Herodotus gives for the four Kings of the Medes amount to 150 years (53+22+40+35=150), while we are also told that the Medes ruled Asia beyond the Halys for 128 years (including the 28-year period of Scythian domination). This seems to imply that Deioces gained independence from Assyria in -709, but only conquered Assyria in -687. This, however, is flatly contradicted by Herodotus’s own assertions that Deioces only ruled over his fellow Medes and that it was Cyaxares who conquered Assyria. According to Herodotus’ figures, Cyaxares 40-year reign was 634-594.

Herodotus also states clearly that the 520 years of Assyrian dominance immediately preceded the start of the revolts of the Medes and other nations: in other words, when Cyaxares conquered Assyria, the period of Assyrian dominance had amounted to more than 520 years.

In the timeline depicted above, I have attempted to reconcile these discrepancies. I have assumed that the 128 years represent the period of Median independence, and that these followed the 520 years of undisputed Assyrian dominance. This requires that for the first 22 years of his reign, Deioces was a subject king of the Assyrians. He then won his independence, and for more than half a century Assyria and Media coexisted. Finally, Cyaxares overthrew the Scythians and conquered Assyria in -606:

709: Deioces becomes King of Media.

687: Deioces wins independence from Assyria.

656: Deioces dies and is succeeded by Phraortes.

634: Phraortes dies and is succeeded by Cyaxares. Cyaxares besieges Nineveh, but the Scythians attack and defeat him. There follow 28 years of Scythian dominance.

606: Cyaxares regains Median independence and takes Nineveh, bringing the Assyrian Empire to an end.

594: Cyaxares dies and is succeeded by Astyages.

559: Astyages is defeated and dethroned by Cyrus, which brings the Empire of the Medes to an end.

These dates are not identical to those found in modern textbooks, but they are fairly close.

In the next article in this series, we will see how Herodotus’ account of the history of Assyria lines up with that of another historian, Ctesias.

To be continued ...

References

- Robert Drews, Assyria in Classical Universal Histories, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Band 14, Heft 2, 22 129-142, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart (1965)

- Alfred Denis Godley (translator), Herodotus: The Histories, Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1920, 1921, 1922, 1925)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Alan Edouard Samuel, Greek and Roman Chronology, C H Beck’sche Verlag, München (1972)

- Aubrey de Sélincourt (translator), Herodotus: The Histories, Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex (1954)

Image Credits

- Assyria: Philip Schaff, A Dictionary of the Bible, Fourth Edition, American Sunday-School Union, Philadelphia Public Domain

- The World According to Hecataeus: Edward Herbert Bunbury, A History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans, Volume 1, John Murray, London (1879), Public Domain

- The World According to Herodotus: Charles Wyville Thomson (superintendent), The Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger: A Summary of the Scientific Results, First Part, John Murray, London (1895), Public Domain

- Statue of Herodotus (Bodrum, Turkey): Monsieurdl (photographer), Public Domain

- Deioces Commands the Medes to Set Forth on Their Course of Conquest: Louis Boulanger (artist), Public Domain

- The Fall of Nineveh: John Martin (artist), Public Domain

- Herodotus, Father of History: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Online Resources