First, there is an opportunity, and then, there is betrayal.

Moral of the story, ladies and gentlemen. If the stakes are high enough, most modern guys will just jump in there and “have it in your ear.”

The Groundwork: “Emotional Attachment”

The Swing: “Life can't be chosen”

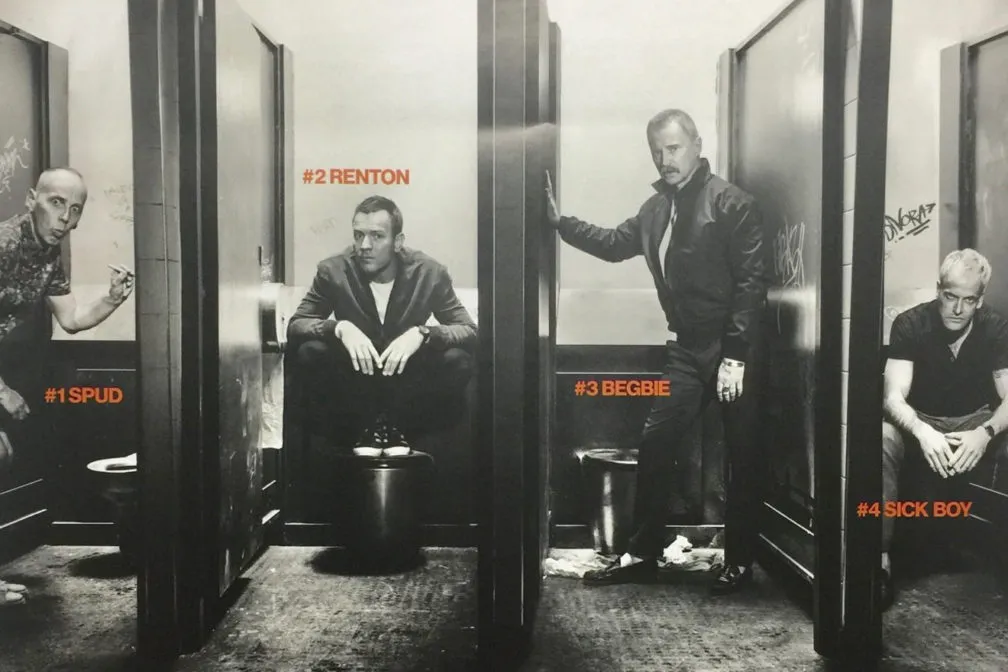

It shouldn't be hard to discern, from the very beginning, whether the characters have aged gracefully. I can see the bald spots and yes they do tend to come with age. I focus on the faces, naturally. It is promptly evident that no hard-core drug user ever ages gracefully. Sick Boy is still dying his hair. The coloured result does not match the original scheme. Things have changed. Begbie is sporting a beer belly now, Begbie is no more the slick bastard he used to be, he is a tired yet aggressive middle aged man. Spud travels the waves of time as if a lemon through a thermonuclear juicer. He has been on the skag for more time than the others. More time than Tommy, who is still rolling around on the floor, locked in his dilapidated apartment, flattening out remnants of a love betrayed, then disguised as excrement dropping out from within an orphaned kitten. Renton has “a metal stent in my left coronary artery” but he feels “good as new” as he strenuously proclaims while ridging his brow. He has been off smack for twenty years. That was his way out of addiction, running away from a grinding cyclic unforgiving environment. Renton has gone on to attend accounting classes in a college, gone on to marry and settle down, gone on to a foreign country where no images linked to a severely depraved, deprived and depressed past exist. Renton is back in Edinburgh after twenty “clean” years of isolation. He is back to make amends with his old life, just as the new one starts, or stops, to give way.

There are no explicit explanations in this story. The plot never actually thickens and one might say that it has been systematically watered down. Everything just falls into place seemingly via the cunning workings of a nefarious serendipity. There are some people who, by the apparent grace of god, cannot within their lives ever cut ties with each other. These guys are just like that. Brought together by luck, proximity and nondescript but violent habitual changes. Brought together by something that could only ever be adequately described as “lack of almost everything”.

Trainspotting 2 reunites the four original silver surfers some 20 odd years later. It's somehow depressing to see so many things left unchanged inside a world that is hell bent on changing. It's somehow relieving to recognise that everyone remains still that old known asshole.

This film makes no bold claims, it does not re-invent the wheel. It does boldly and shamelessly admit, in vivo, that protagonist to antagonist, everyone is living and somehow badly thriving in the past. Hanged about their numberless age, the bad boys remain bad, the good guys remain good, the thieves and scaremongers insist on plying their trade and the messiahs who seem to be everywhere drop about unexpectedly and hold over a hole threaded hand forking out dirty cash in exchange for vices they are all simultaneously albeit privately aware are doing them no good.

The Skagboys are choosing life every minute of every day. The “life” of an opiate addict is still a “life” and indeed a chosen one. One will surely be aware of this after the first initial hit. One will surely be aware of this after the millionth chase after “the dragon”.

“I want a fuckin' hit!”, Renton feverishly exclaims in the first chapter. Opium suppositories never make the grade. The “life” advertised on shop windows doesn't make it either. Twenty years after, all the time sucked within the polymer walls of a gnawed up syringe seem to reveal the truth of the situation. You don't choose life, life chooses you.

Mark Renton's fall, rise, and subsequent fall serves to exhibit one very specific trait of human character. Psychological submission to a synaptic antagonist that acts disruptively against a current habitual situation. Love is such a substance. Heroin also. Unbridled sex. Fervent churchgoing. Depression and lethargy. We only long for our livelihood to go “well” so we can have the chance of dismantling it, setting it on fire and curl around its embers, watching hope burn. A tidy life is only fitting for the dead and all us jokers love our ego so much we are edging to see it transformed into a lowly stampeded pulp. It's only through this “spit and grapple” mechanism that we get to have a chance in rebuilding everything once more from the ground up or alternatively to just sit around and mumble shortened words of denigrated praise at ourselves. In both cases, somehow we, as them, manage through a demonstratively dismantling process to instill “perceptible meaning” at what we almost always affectionately call “our life”.

The toddlers that were once brought up together into communal alleys, fleshed and formed into full blown junkies, supported by the blind railway of youth and wanton rebelliousness are gone forever, despite their obvious attempts in rekindling their relationship with their former “innocent” selves. They now know, after years of trying, that they are not cut for normality, whatever that may be. They now know they are fuck-ups and have accepted their “role” quite well. Even Renton's long and short bouts in and out of sobriety, his partial foray into wisdom by reformation and restrained holier-than-thou attitude will not, as portrayed in this film, prevent another relapse.

These “trainspotters” were designed and sent out meaning to scam the world. Once together they have no other option but to scavenge their way through formality and con their dreams into believing a jaded version of orthodoxy. These guys survive their days inch by inch and hold no trust amongst them and even to themselves. Still, despite all odds they make do even as their world insists on falling down around them.

The characters in the original film are frustrated, short sighted, morally depraved and animalistic adolescents. The characters in the sequel are frustrated, short sighted, morally depraved and animalistic adults, but their re-introduction adds an important twist. They all have, somehow, families of their own. They all now have, even in its clustered but free-forming version, a responsibility beyond themselves and they all come to acknowledge that, revealing their own true human sensibilities all in their respective individualistic fashion.

Spud recognises the fact that his ongoing addiction and dependence on heroin has deprived him of his more fruitful years, truncated his relationship with his long-standing girlfriend and only son, rendering him helpless, stuck in a loop where all clocks are one hour ahead of his time and he is one hour late in rectifying any previously committed mistakes.

Begbie remains a psychopath hell bent on raping a world he vehemently rejects and is being rejected by. Stuck in a prison for an undisclosed crime and time, still angry and vindictive, escaping only by inflicted self harm – a hidden parable in the act, tortured and motivated by boiling thoughts of revenge, he will not change his way towards the world and himself, but in a touching scene of honest goodbye to his family, he will embrace his son offering apologies and blessings, before continuing on the same savage life act he always did, ending it by karmically returning back to the can.

Sick Boy, slick but weathered, now addicted to cocaine, consistently amoral and admittedly a “bad person” as described by a character on screen, high strung and angry still hides any sensibilities he has left behind by allowing himself to be drawn well into his own scams which range from blackmail and extortion to identity and card theft. Despite his profound anger towards Renton, his best friend, he still is remorseful towards his spiteful plan to mentally and physically torture him as revenge for his previous “betrayal” of walking away with all the shared cash the group made out of a cocaine deal. He is obviously still very attached to childhood and adolescent memories and it's this peculiar grab with the past that eventually leads him to help Renton against his pursuing enemy, Begbie.

Renton is still infused by a messianic complex he does not consciously understand or recognise. He returns back to the locale of his “glory” days, a city visibly changed (just like him) and unwelcomely foreign (exactly just like him). He is back to confront, redeem and reconcile with his past. He is back to save the ones that cannot, will not and won't not be saved. It's unclear if he includes himself in that lot. In his own mind he has helped everyone. In his own mind he is better than anyone.

“You are a tourist in your own youth!”, Sick Boy spats out to Renton but this line could be fittingly adapted to be mouthed by anyone towards anyone. They are all tourists in their own youth. The viewer is certainly a tourist in their very own youth. Hallmark of a life not lived forwards.

Renton is not a person that knows how to let go. Granted, the requirements of a true sequel demand the main protagonist to be strongly at odds with letting go – this is how a story, a lore is continuously kept alive. Renton leaves his past behind at the end of the first film, only to come full circle in the second and return, humbled, just like the prodigal son he is but unapologetic despite his seemingly generous offerings to his mates who, one by one are initially very displeased to meet him. He comes back just in time to save Spud from expertly suffocating in his own vomit and gets a belated strafing scolding from him. He comes back just in time to return Sick Boy's part of the cut from the final heroin deal and help him bounce off lightly through a conviction sentence igniting this way his sincere ire and thirst for revenge. He comes back just in time to give a slinking Bebgie the chance of having some real purpose in his life for a change – that of killing him. Renton is back in a vain attempt to mend his own life, which has been, unsurprisingly rendered obsolete once again.

Still everybody, despite “having it in the ear” from Renton are glad to see him and are openly or secretly vocal about it. “Everybody” counts everyone not being Begbie of course who just wants to see Renton hanged. The same sentiment is being initially shared by Sick Boy who declares his intention to “make him suffer” but later is seen actively protecting his old friend and eventually, with the help of Spud, saving his life from the hands of a raging Begbie.

I'm noting this down for emphasis and for you the reader to draw your own conclusions. Renton is almost always the cause for someone being fucked over. In the first film Renton fucks over Tommy, first by stealing his intimate sex tape, causing him to break up with his girlfriend and slip into depression. He then finishes the act by selling Tommy his first hit, which will eventually lead him to addiction and death. Renton fucks over Sick Boy, Begbie, and to a lesser extend Spud when he takes off in the middle of the night with the deal money. He also fucks over his parents who have to accept their son being a junkie by eventually walking out on them. In the second film Renton fucks over Spud by interrupting his suicide attempt (admittedly this can be also seen as a good thing). He then fucks up Sick Boy by stealing his girlfriend while being adamantly refuting in admitting his intention to do so. Finally, Renton fucks up Bebgie for the second time when he becomes a catalyst for his imminent return to prison. Renton is always in the scene demanding “his fucking hit” one way or another. Surely one can argue that each happening could potentially be exemplary in teaching a character some valuable lesson but the focal point of this note is to demonstrate just how disruptive Renton's input into other people's lives is.

Still, Renton makes it every time, whether whilst beating his brains “with the liquor and drugs” or while being a clean cut motivational speaker. I can safely argue that there is no real intentional malice in any of Renton's actions, but the reality presented in the films reveals him to be a creature of adversely serendipitous manner.

The Technical Lowdown

This sequel plays out in a very concise Hollywood-esque manner. It is more about action than drama, and it's more about affinity than comedy. This is a film that attempts to stimulate nostalgia, both in the film canon and also in our own personal lives. Romanticism enhancing the sense of past “betterness”. Smug rebelliousness at its very best. There is a visible attempt of the characters to reconnect with some idealistic notion of lost childhood innocence, courtesy of the many cut-scenes alluding to a “care-free prepubescent past”, but an endeavour such as this is going to be futile considering that innocence got vaporised into smoke, injected and plunged during the character's addict years, which somehow seem to consciously extend to today and beyond.

Cinematography and scene photography sticks to original standards as is unorthodox camera angle placements and dramatic freeze-ups which are used, poignantly but effectively in order to highlight temporal emotional intensity. It is important to note the overall color palette throughout the film which lacks the original's selectively-chromatic intensity but instead chooses to apply a more diffused approach, smoothing out shadows and undertones, using standard color balancing in normal transitional scenes and enhancing the highlights in key scenes, utilising bright pastel colours in eerie but comforting glows.

The central theme of the movie might be “Betrayal” but the plot-line to plot-line progress through the film permits an air of “cohesive abstractive reform” to seep through the practically bland dialogues during character interaction. The Skagboys are all tired of constantly losing and they long to be eventually saved.

This film is not about drugs any more.

This film is about the characters (and vicariously the viewers) actively working into transforming or re-making their lives, and doing it effectively better for the first time, even if said process does naturally drag them through what is the only firmly known attribute of their operational matrix, crime and delinquency.

It would be impossible for anyone to conduct a true review of a Trainspotting film and not mention the “Choose Life” Monologue, otherwise known as the films mainstay and justification of cause.

The obviously fan-bait inclusion of an updated version of The Monologue when played out feels like an après-vie inclusion to a film strictly intending on maintaining the highest possible permissible links to the original. This is ultimately about a trip down memory lane. This “updated and modernised” monologue is an attack on contemporary life, a critique about everything and anything that is designed to make you “want to stand out” from the crowd (much akin to drug taking). By ultimately removing the true(er?) substitute (for all) of heroin one is left without a viable answer or alternative to the Monologue's accusing barrage. Why do anything over something other?Why “choose” something over another thing? The awkward pause after the Monologue's delivery only leaves something akin to nihilism for aftertaste. Renton himself feels uncertain for the result offered, uncomfortably mumbling as if issuing an apology to his receiving counterpart, “It amused us at the time”.

The end is kept intentionally ambiguous. It is unsure if what Renton acquired in the end (evident of the Prodigy's remixed “Lust for Life” playing in his bedroom turntable) is the knowledge that “having it in the ear” is what exaggeration and drama is to normality – a minor insignificant and usually useless upsetter. It is always possible for drama to happen but if it does, it will be more like an unknown spice in your concoctive seductive mixture than a turnblock in the middle of your super-highway and that the bounce-back (providing that a relapse does not manage to seize the reigns) will surely catapult one's perception to finer, well adjusted and balanced lengths.

It's either that, or back on the smack.