Welcome to the third installment of my series detailing the issues plaguing private higher education. This chapter will focus on retention, attrition, and the financial consequences thereof. If you're wondering where the hell I get off discussing this, or want to know more about the subject, feel free to check out my other posts:

There are three crucial figures that colleges and universities obsess over: first-time freshmen; retention; graduation rate. All of these go hand-in-hand and the federal government asserts an incredible amount of pressure when it comes to these numbers, but you'll learn more about that in Chapter 5. Ultimately, it boils down to butts in seats. Get them there, keep them there, and then make sure they leave within 4-6 years. Chapter 2 focused on getting them there and keeping them through week 3, which is the industry standard for when institutions pull their data. At this point, students are far less likely to drop out during the rest of the semester and so at week 3, a first-time freshman transitions into retention. In other words, those who counted towards freshmen enrollment will then be tracked into their sophomore year to determine an institution's retention rate*.

Where recruiters in admissions departments have sales quotas to meet, once on campus, it becomes everyone's job to retain students. This permeates throughout every division of a college. Institutional Advancement sets fundraising goals in order to alleviate some of the financial burden placed on Pell-Grant eligible, i.e., economically struggling students†. Financial Aid or Career Services will hold workshops that focus on student loan education and financial literacy. The list goes on, but two divisions play the greatest role in student retention: Academic Affairs and Student Affairs. If you look at any institution, these two divisions are responsible for the vast majority of costs (athletic departments may be an exception). However, there are political and ethical ramifications to this.

Historically, academic affairs paid no heed to retention. In fact, the sentiment leaned more towards a lack of sympathy and an expectation for students to prove themselves. This is still true at many - often more prestigious - institutions; however, the administration at most colleges and universities have placed retention expectations on faculty. This has been very contentious as faculty typically hold their positions for reasons that don't include teaching. Perhaps they are cancer researchers, famous artists, or working on their sixth book. They don't become faculty to teach, but to have access to fellow great minds and funding; teaching is often something they have to do. There are exceptions to this; I know countless faculty who do it solely for the rewards of teaching a group of students, mentoring those who are struggling, and watching them excel throughout their 4-6 years, and these faculty are the most admirable. But for the rest of them, retention is a new burden that detracts from their professional practice (the primary reason they were hired) and their ability to participate in faculty governance.

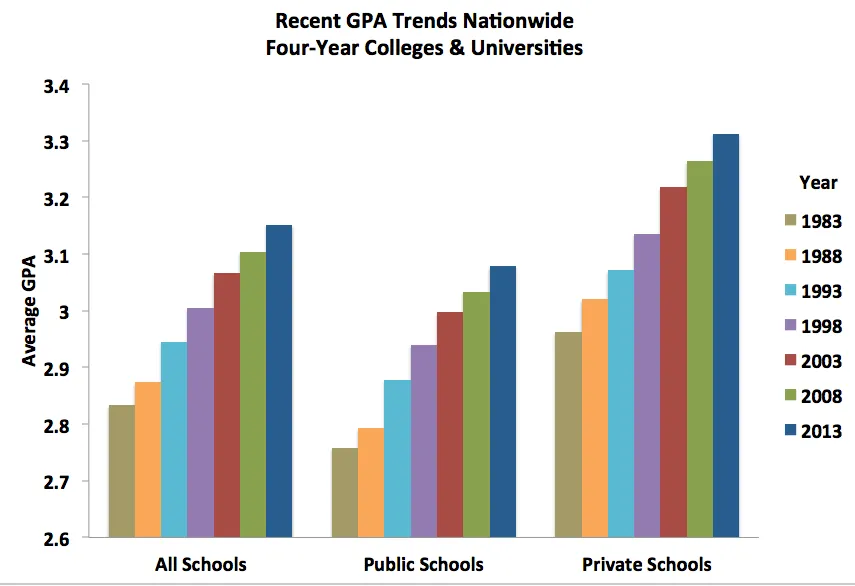

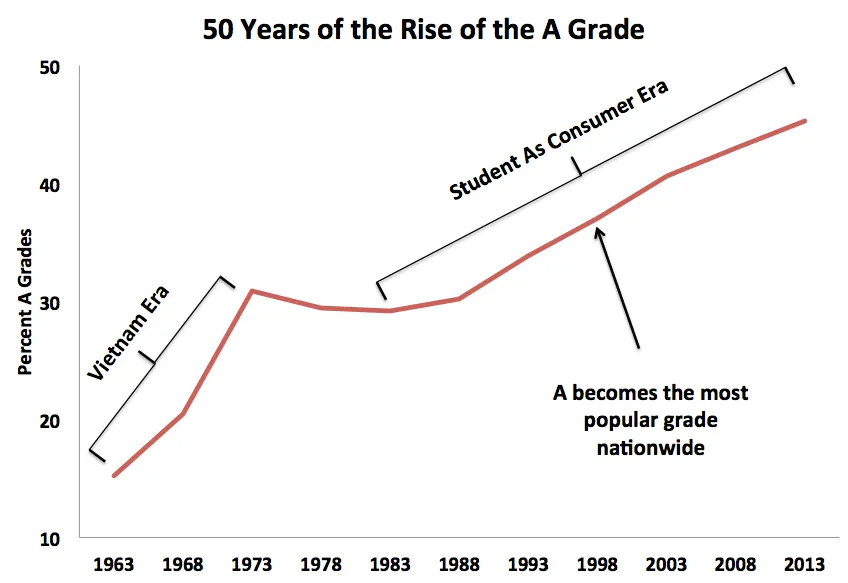

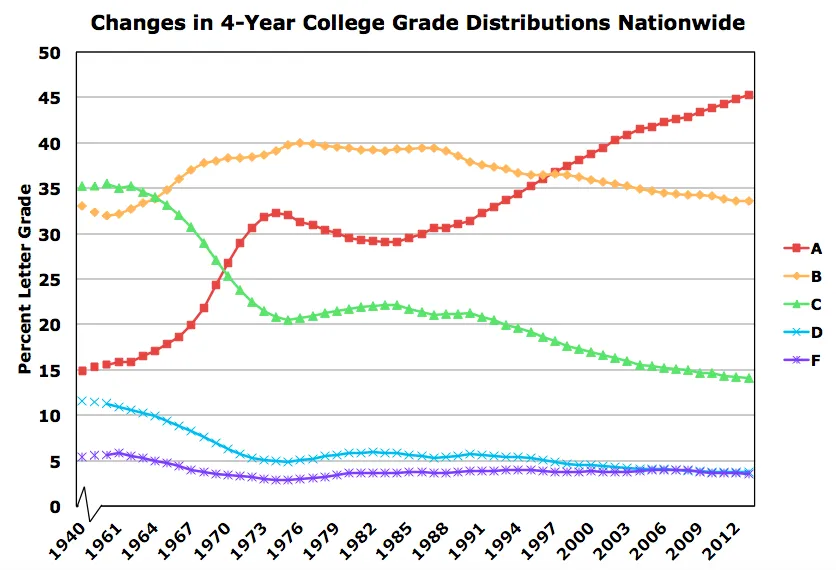

This burden can take different forms. For some, it's self inflicted, indicative of a dedicated faculty body that genuinely wants to see students and the institution succeed. They'll do anything they can, including being on call 24/7, taking them on weeklong field trips, giving weak feedback, excusing excessive absences, etc. Ultimately, students abuse the faculty's generosity and the faculty member burns out. Plus, students don't learn the value of meeting deadlines or taking constructive criticism. This pressure can also be top-down. Imagine you're a faculty member who's a tough but fair grader. One day, you get an email from your department chair or even the school dean, inquiring as to why you have such a high percentage of students getting D's or F's. In your mind, they didn't demonstrate that they learned the material and/or didn't complete the work and/or didn't show up and their grades should reflect that. But what would you do if the person who signs your checks, approves your research funding, and ultimately decides whether or not you get tenure starts asking questions about tough grading? Most give in, resulting in grade inflation. The following images (c/o http://www.gradeinflation.com/) capture this across public and private institutions:

Five-Year Grade Point Averages from 1983-2013 by Institution Type

Average Number of A's Awarded since 1963

Note the increase coincides with events outlined in my historical summary of academic dysfunction

Grade Distributions at 4-Year Institutions since 1940

Note: these datasets do not include community colleges

These inflation rates do not coincide with improved performance at the K-12 level (http://www.gradeinflation.com/ details this and shares its research methods), meaning that students are not performing better and as a consequence, more students are receiving degrees without performing to the expectations of yesteryear. They're not getting what they paid for and subsequently the value of their degree(s) is diminished.

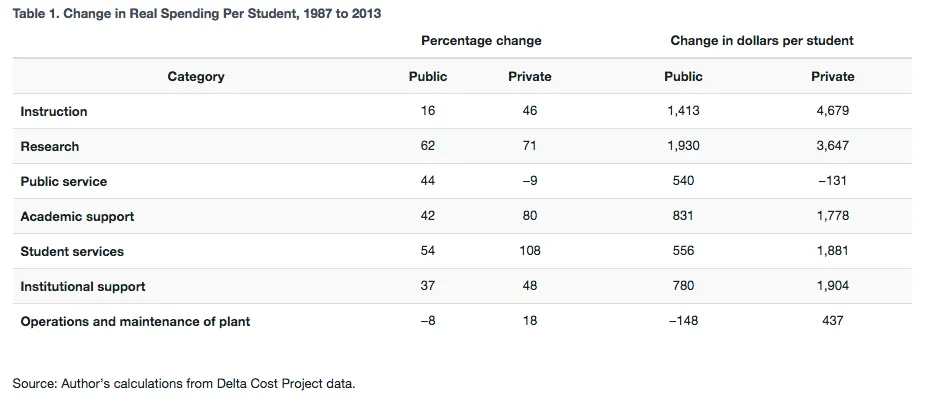

In addition to the ethical ramifications of grade inflation, Student Affairs divisions are guilty of providing a gluttony of services the are directly responsible for skyrocketing tuition rates**.

https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/2016-economic-commentaries/ec-201610-trends-in-expenditures-by-us-colleges-and-universities.aspx

As outlined previously, this is due on part to institutions competing with one another, but it is also due to students expecting more. Students enter college demanding better dorms, food, tutors and hours, student clubs, labs, dances, wifi, stadiums, etc., etc., etc. A firehose of services has been opened and yet somehow students are still thirsty. They don't stop to think about the fact that their engorged student loans or thinned parental wallets is what pays for it. They pay more, so they want more, so they pay more and before you know it, you have a perpetual motion of tuition increases and services until at some point the whole thing breaks.

And that is where we are right now in American higher education. Schools, GOOD schools are closing their doors because not enough people can pay for the tuition necessary for them to compete with bigger, more well-endowed institutions. As a result, there will be fewer options for students, putting institutions in the position of being able to cherry pick who does - and doesn't - get to enter into their ivory towers. There are some institutions that should close, but not the majority of them. Education is not a game of survival of the fittest; access is key and the fewer institutions there are, the more people won't be able to attend.

*Retention is tracked for every year: freshman to sophomore; sophomore to junior; junior to senior. The Federal Government emphasizes freshmen-to-sophomore retention as a measure of an institution's recruitment tactics. If retention is low, chances are they have some questionable recruitment and enrollment practices. If it's high, it means they recruited a "healthy" student body population that has a great chance of matriculating, i.e., graduating through a traditional academic plan.

†It is taboo to say poor, broke, inner-city youth, or anything of the like at these places. Instead, people refer to students from lower socio-economic status as "Pell-Grant eligible," which is a Federal grant awarded only to students whose FAFSA demonstrates a level of need. Truly savvy academicians will refer to these students as "SES." While technically more accurate, it's still an politically correct way of skirting the whole more-poor-people-happen-to-be-minorities issue.

**For the purposes of this series, Student Affairs should include all student support services, both academic and ancillary (health and wellness, counseling, learning support services, etc.). The dividing lines between Student and Academic Affairs varying between institutions and while there are commonalities (e.g., the library is almost always in Academic Affairs), my point is more on the student services than on which division is hosts which services.