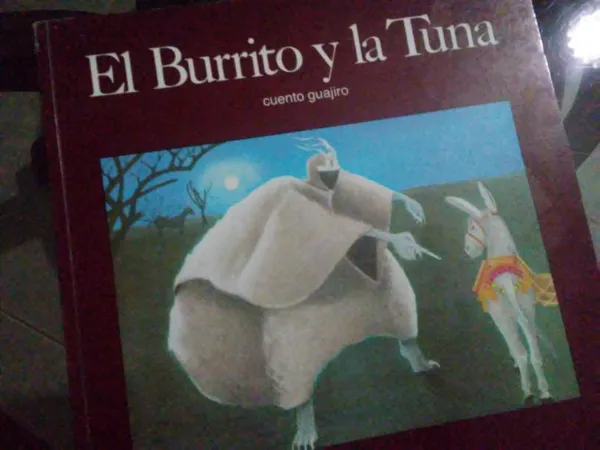

Canela reading from her copy of El burrito y la tuna. 5th ed. Caracas: Ediciones Ekaré, 1997. 24-25. - Picture of my own

A child may not be interested in a determined literary text because they genuinely have no interest in it, or because they lack the tools to identify such interest. But if we intermediaries (the ones who present the child with the literary piece) understand a literary text fully, there are great chances for us to make this work of literature interesting to our children. This is why I do this; I comment on Children’s Lit and hopefully I’ll be helping somebody to become a reader or a better reader.

El Burrito y la Tuna (1979), a Book for Any Child in the World

For a quarter of century Venezuelan Wayuu Ramón Paz Ipuana, a teacher, a researcher, a poet has been walking among his Guajiro ancestors. The author of El Conejo y el Mapurite and Ale’eya also wrote The Little Donkey and the Tuna Plant (a literal translation of the book title into English), the story I am about to comment in the following lines.

For those who are not familiar with the literary oral tradition of the indigenous people in my country, these words by Ramón Paz Ipuana may be helpful:

Magic is one of the first moves made by man in order to get into the world of tricky games and into a prestidigitating nature. The word, the gesture, the language, were the first enchanting tools to guide human thought. The hinge upon which all of the Wayuu culture rests is composed of three fundamental and nontransferable principles:(From La literatura wayuu en el contexto de su cultura, p.71, n.d. My translation).

- The fabulous world of dreams

- The irreversible world of magical-religious beliefs

- The poetic worldview of their fantastic, mythic world, which is displayed in their chants, tales and narratives. All expressions of indigenous oral literature fall under the wonderful, the extraordinary, the unlikely.

What Does This Story Tell?

The Little Donkey and the Tuna Plant tells the story of a Guajiro (an indigenous man from the Colombian-Venezuelan Guajira), his donkey and the Wanuluu (Evil itself). The man sets off to a four day journey; he is riding his donkey, which also carries his supplies.

My copy of the 5th edition of the book - Picture of my own

One night, the uncanny whistling of the Wanuluu announced his presence. The man jumped out of his “chinchorro” (some sort of hammock) and hid behind an olive tree, leaving his donkey to confront the vile creature by itself.

The Wanuluu was a horseman who rode a “horse of shadows.” He had no face and wore white feathers on top of its head. The blows of his whistling dagger were lethal. He got off his horse and asked the donkey for his master many times, but the loyal animal gave him no answer. The Wanuluu killed the donkey, which gave him a good fight first while its master watched from behind the olive tree without the least intention of helping his faithful companion.

When the man came back to his village, having left the dead donkey behind, he bragged about having defeated Wanuluu by himself. Meanwhile, the corpse of the animal turned into a cardon. The time came for the man to come to the place where the nefarious being had killed his donkey. Only when he felt tired and thirsty he remembered the animal. He looked around but could not spot the donkey; instead, he saw the cardon full with red fruit. He ate from it, and also from the honeycomb hidden among the ribs. As he tasted the delicious honey, he drooled and the drops ran down his face and his body, which began to turn green and be covered with spines and yellow flowers. The man became Jumache’e, a tuna plant. Tuna and cardon became inseparable ever since.

During the rainy season, tired travelers are happy to see the yellow flowers and the red fruits.

What Is There to This Story?

The characters are rather plain instead of round: throughout the story, the man remains selfish (and a coward); the donkey, loyal (and brave); and the Wanuluu is just evil. Like in any myth, there is no need of a moral or any display of justice; things are what they are.

Highly probably, the motif of this story, the plants, appears out of frank imagination. We often see shapes in the clouds and trees; this might not be the exception. Children can feel identified with this practice, easily.

If after going outside and asking your children or students what shapes they see in the trees and what characters from real life they think they had been in a magic past, you feel like this is not enough as to make them feel closer to the magical thinking of the indigenous people and their own, you can always play another card. Have them appreciate how in the end man and animal are bound to each other and both of them, to this earth. Have them also evaluate the fact that when EVIL came, only the human soul was as weak as to fall under its influence. Tell them about donkeys; they are some of the most amazingly faithful creatures men should be lucky enough to have as companions.

Thanks for reading about Children's Lit.

Posted from my blog with SteemPress : https://marlyncabrera.timeets.com/2019/01/09/the-little-donkey-and-the-tuna-plant/

Soy miembro de @talentclub.