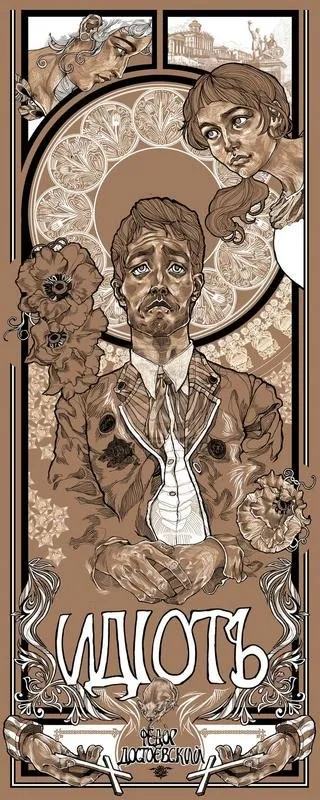

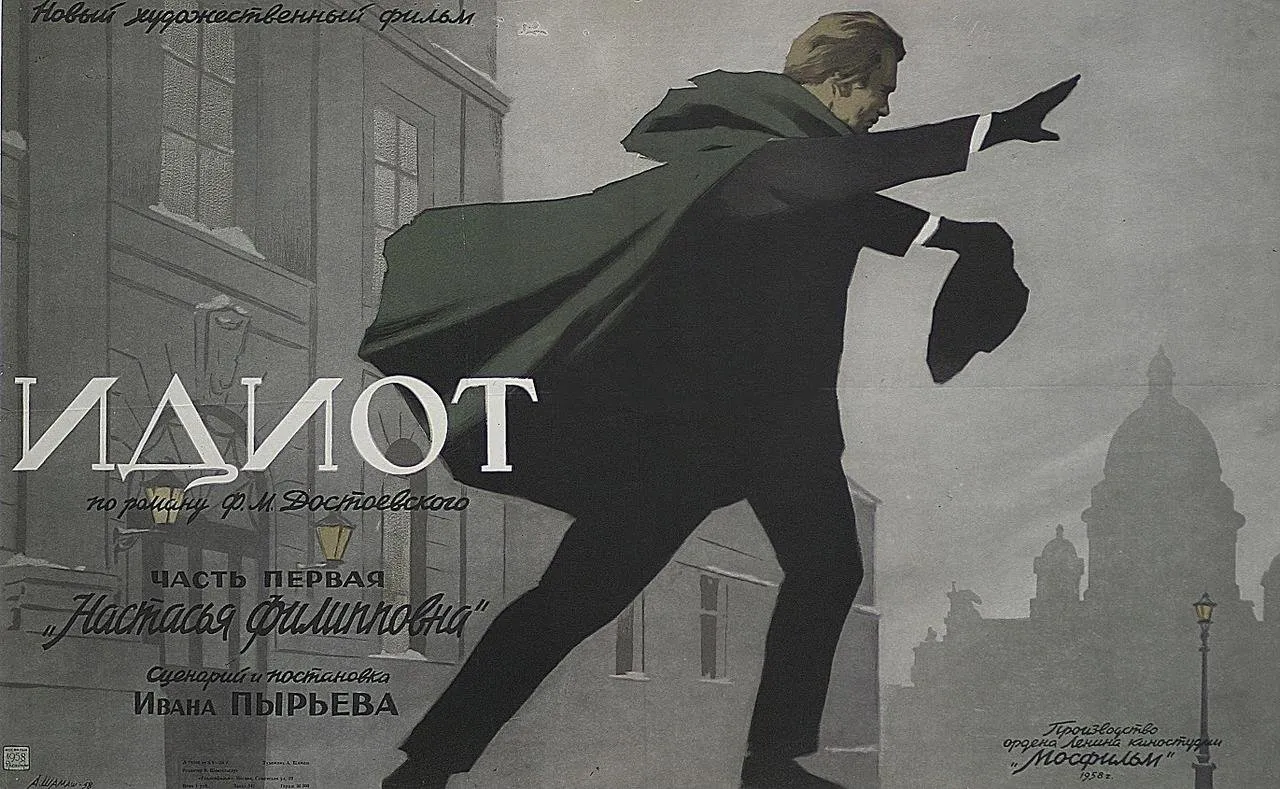

Dostoevsky's THE IDIOT

BOOK I - CHAPTERS 3 / 4 / 5

(Source)

(Source)Cast of Characters

- Prince Myshkin: 26 years old, the Idiot himself.

- General Epanchin : 56 years old, former soldier, rich landowner and investor.

- Gabriel “Gania” Ardalionovitch: 28 years old, secretary of Epantchine.

- Elizabetha Prokofievna Epanchin, born Myshkin: a “proud” woman, mother of three.

- Alexandra, Adelaida, and Aglaya Epantchine: three young ladies.

What is happening?

In fact, I have a certain question upon which I much need advice, and do not know whom to go to for it. I thought of your family when I was passing through Berlin.

A bit later on, when Prince Myshkin is telling about his story in Switzerland, the author also adds that:

because of a certain matter which came to the ears of the latter, Schneider had despatched the young man to Russia.

However, we will never know what is this “matter” about because by the end of the chapter, the General Epanchin will cut the conversation short before Myshkin can really talk about it:

The general left the room, and the prince never succeeded in broaching the business which he had on hand, though he had endeavoured to do so four times.

I think that Dostoyevsky is doing that on purpose, and plays with the audience. There is a mystery there, or a simple trick to keep the audience curious and attentive. And it works!

However, even if Myshkin can’t explain himself, he has made his honesty and his goodness so obvious that the General Epanchin is obviously conquered and eventually agrees to help him, on the pretext of his calligraphic skills, by providing him with a job AND a lodging:

I shall find you a place in one of the State departments, an easy place—but you will require to be accurate. Now, as to your plans—in the house, or rather in the family of Gania here—my young friend, whom I hope you will know better—his mother and sister have prepared two or three rooms for lodgers, and let them to highly recommended young fellows, with board and attendance. I am sure Nina Alexandrovna will take you in on my recommendation.

However, Dostoyevsky makes sure to let us know that the General’s generosity is not totally uninterested - which makes this whole scene looks like in my mind a kind of chapter from Balzac, with people of the XIXth century French society trying to get advantages and favours from one anothers:

Taking so much interest in you as you may perceive I do, I am not without my object, and you shall know it in good time.

If the prospect of having to share lodgings with the Prince embarasses Gabriel’s secrety, this one shows absolutely nothing about it who even goes as far as sharing a cigarette with the Prince and asking him how he finds Nastasia, the woman he may soon marry. Something shows that this woman will be at the center of a love triangle between “Gania”, Myshkin and Rogojine - the dark brooding figure met in the train, and the evidence is that - before Dostoyevsky shows the encounter between the two last members of the Myshkin family - he takes upon him to tell us a long digression about that mysterious Nastasia.

It seems that Nastasia was a poor country girl, who was taken care of by a rich landowner, brought to town, and who had a total “control” over her protector, but not of the sexual kind:

He was afraid, he did not know why, but he was simply afraid of Nastasia Philipovna. For the first two years or so he had suspected that she wished to marry him herself, and that only her vanity prevented her telling him so. He thought that she wanted him to approach her with a humble proposal from his own side. But to his great, and not entirely pleasurable amazement, he discovered that this was by no means the case, and that were he to offer himself he would be refused. He could not understand such a state of things, and was obliged to conclude that it was pride, the pride of an injured and imaginative woman, which had gone to such lengths that it preferred to sit and nurse its contempt and hatred in solitude rather than mount to heights of hitherto unattainable splendour. To make matters worse, she was quite impervious to mercenary considerations, and could not be bribed in any way.

Maybe because of my lack of understanding of this situation, I’m unable to really understand what’s going on there between Nastasia and her “protector” but I guess we will learn more as soon as Dostoyevsky will want.

Eventually, the reason this story is introduced is because it fell to the General Epanchin to broker some kind of deal between Nastasia and her protector: and the General had no better idea than to suggest a wedding between Nastasia and his secretary “Gania”.

Just when Prince Myshkin appears at the door of the Epantchine’s, all the threads of that wedding are weighing in the balance, between Nastasia has not yet made her mind. Will she? will she not? How is Myshkin going to influence that decision?

We are left with that question pending just when Myshkin is thrown to her relation the Generale Epanchin, born Myshkin, and her 3 daughters who are having supper. He is thoroughly cross-examined by these four women, which does not seem to bother him: he tells the things about his time in Switzerland and his illness as candidly as possible - making him an easy target for the young women:

“I have seen a donkey though, mamma!” said Aglaya. “And I’ve heard one!” said Adelaida. All three of the girls laughed out loud, and the prince laughed with them.

If the Prince laughs at the joke, the mother is embarrassed and her last doubts about the Prince, who she thought was a lunatic madman, disappear. She is on his side from now on and intently listens to his story.

From an idiot, or a donkey, the Prince eventually becomes a kind of philosopher, when he tackles (again) the subject of death and death penalty. There is a long description of the execution scene which was depicted in the chapter II, and once again the Prince clearly states that this scene had a huge impact on his mind and vision of the world.

He is so convincing that, at the end of the chapter 5, the three Epanchin daughters are completely won over by the Prince and want to know more. They even suspect that there is a love story behind all of that… And they are kind of right: but Dostoyevsky cuts short at that moment and will tackle that subject in the following chapter.

My favourite moment/scene

Certainly he would, I should think. He would marry her tomorrow!—marry her tomorrow and murder her in a week!”

And to think that he says that about a man he just met in a train and about a woman he just heard about is quite astonishing. Does it mean he has some kind of vision of the future, or an innate sense of human nature? There is a violence behind those words which strikes a strange figure with the calm and peaceful and loving figure of the Prince.

Memorable quote(s) from this chapter

Sometimes I went and climbed the mountain and stood there in the midst of the tall pines, all alone in the terrible silence, with our little village in the distance, and the sky so blue, and the sun so bright, and an old ruined castle on the mountain-side, far away. I used to watch the line where earth and sky met, and longed to go and seek there the key of all mysteries, thinking that I might find there a new life, perhaps some great city where life should be grander and richer—and then it struck me that life may be grand enough even in a prison.

The solitude of the Prince in his Swiss exile is made bare. However, rather than a bane, it turned into a kind of epiphany!

There was a very strange feature in this case, strange because of its extremely rare occurrence. This man had once been brought to the scaffold in company with several others, and had had the sentence of death by shooting passed upon him for some political crime. Twenty minutes later he had been reprieved and some other punishment substituted; but the interval between the two sentences, twenty minutes, or at least a quarter of an hour, had been passed in the certainty that within a few minutes he must die. I was very anxious to hear him speak of his impressions during that dreadful time, and I several times inquired of him as to what he thought and felt. He remembered everything with the most accurate and extraordinary distinctness, and declared that he would never forget a single iota of the experience.

As an echo to the previous quote, we have here its almost equivalent, but in time, not space: you can live in 20 minutes a full life, with all its ups and down - if you don’t waste that time - which means if you KNOW that you are going to die.

Quotes taken from: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/2638/2638-h/2638-h.htm

Conclusion

Previous articles

Dostoyevsky's THE IDIOT Chapter I & II - Steemit Bookclub Launched!!!