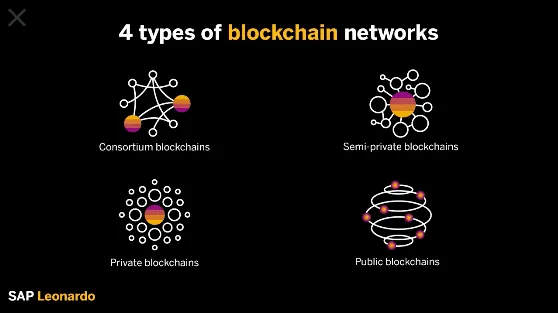

As people began to understand how blockchain works, they started using it for other purposes: as data storage for things of value, identities, agreements, property rights, and a host of other things. Ethereum, which will be one of the main focuses of this book, is to date the most comprehensive blockchain innovation after Bitcoin. Like cloud computing implementations, different types or categories of blockchain have emerged. Analogous to the cloud, you have public blockchains that everyone can access and update, you have private blockchains for just a limited group within an organization to be able to access and update, and you have a third kind, a consortium of blockchains that are used in collaboration with others. While working on Wall Street, we saw this consortium type of arrangement as very common between five of the larger investment banking firms. The consortium facilitated trades at an institutional level among the members, so it makes sense that blockchain as a financial technology tool would emerge in this way. The following sections are a quick exploration of each blockchain type.

Public Blockchains

A public blockchain is one that initial creators envisioned as: a blockchain for all to be able to access and transact with; a blockchain where transactions are included if and only if they are valid; a blockchain where everyone can contribute to the consensus process. As discussed, the consensus process determines what blocks get added to the chain and what the current state is. On the public blockchain, instead of using a central server the blockchain is secured by cryptographic verification supported by incentives for the miners. Anyone can be a miner to aggregate and publish those transactions. In the public blockchain, because no user is implicitly trusted to verify transactions, all users follow an algorithm that verifies transaction by committing software and hardware resources to solving a problem by brute force (i.e., by solving the cryptographic puzzle). The miner who reaches the solution first is rewarded, and each new solution, along with the transactions that were used to verify it, forms the basis for the next problem to be solved. The verification concepts are proof-of-work or proof-of-stake.

Consortium Blockchains

A consortium blockchain such as R3 (www.r3cev.com) is a distributed ledger where the consensus process is controlled by a preselected set of nodes—for example, a consortium of nine financial institutions, each of which operates a node, and of which five (like the US Supreme Court) must sign every block in order for the block to be valid. The right to read the blockchain may be public or restricted to the participants, and there are also hybrid routes such as the root hashes of the blocks being public together with an API that allows members of the public to make a limited number of queries and get back cryptographic proofs of some parts of the blockchain state. These sort of blockchains are distributed ledgers that may be considered “partially decentralized.”

Private Blockchains

A fully private blockchain is a blockchain where write permissions are kept centralized to one organization. Read permissions may be public or restricted to an arbitrary extent. Likely applications include database management and auditing internal to a single company, so public readability may not be necessary in many cases at all, though in other cases public auditability is desired. Private blockchains could provide solutions to financial enterprise problems, including compliance agents for regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), anti–money laundering (AML), and know-your-customer (KYC) laws. The Hyperledger project from the Linux Foundation and the Gem Health network are private blockchain projects under development. See Chapter 8 for a detailed description of Hyperledger and other private and consortium blockchain technology.