How Edgar Allan Poe Tricked Readers into Thinking his tale was true.

In 1999 a pair of unknown directors changed the face of on-screen horror forever. The Blair Witch Project spawned an entire genre worth of camera shaking imitators, some good (Rec. Paranormal activity, Borderland and even Cloverfield) some unspeakably bad ( seriously mate, what is that even supposed to be? It looks like a fucking Big Mac filmed on a potato.) but one of the key drivers of the movie’s success, aside from its stylistic choices, was the marketing campaign that preceded it. For a few glorious months in 1998/9, people genuinely thought it was real.

By fabricating a legend, faking documentation, setting up a website on the nascent internet and firing out a ton of pseudo-official looking copy about their fictional witch, Myrick and Sanchez managed to convince early audiences that what they were about to see was in fact a bone fide example of ‘found footage’ before that term took on its now swearword like quality.

By Eleanor Sciolistein

Featuring unknown actors, filming with low quality equipment and doing away with typical staples like tight scripting and studied framing of shots, Blair Witch created the illusion of amateurish authenticity (as opposed to the amateurish authen- shit- aty of the sequel).

The campaign came at a time when people were much more prepared to believe what they read online and the directors used that fact to their full advantage. Whatever your feelings about the movie itself, it has to be conceded that the directors were both very clever and very successful in their approach. They were not however, the first.

The process of presenting an entirely fictional work of horror as if it were true, is as old as the genre itself and can be traced back to the earliest oral traditions of ghost stories told by the fire, often related as having happened to a ‘friend of a friend’ (though often the notion that the teller would have a friend at all was suspect in itself).

In print too, this technique has a long history, with some of the earliest gothic horror pieces ever written being presented anonymously, so as to increase the terror therein by making it more likely that the readers would give some credence to the texts authenticity.

The true trailblazer in this respect however, and someone whose attempts at duping the audience laid a virtual blueprint for the path taken by The Blair Witch Project directors, was none other than the 'Godfather of Gothic' himself, Edgar Allan Poe.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning said that Poe's talent lay in making ‘horrible probabilities seem near and familiar’. She wasn’t wrong. When Poe released the horrible probablities his story ‘ The Facts in The Case of M.Valdemar’ in a gentlemen’s magazine they were disturbingly near and familiar. As the title of this article suggests, people wholeheartedly believed it.

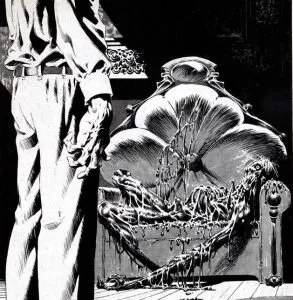

The story itself, which is a classic you should go away and read right after this article if you haven't already, centres around the eponymous M.Valdemar who, in poor health and close to giving up the ghost, agrees to allow himself to be mesmerised (the precursor to hypnosis). Valdemar is duly placed into a hypnotic trance before the point of death to see if this has an effect on the consciousness and the preservation of ‘life’. Look away now if you don’t want spoilers ( seriously though, it’s been nearly two hundred years, if you consider this a spoiler you really need to remove the digit from the orifice, read some Poe and have a word with yourself).

Predictably, this does not go entirely to plan. Whilst under the influence and still communicating, Valdemar shuffles off the mortal coil whilst still speaking and, in what has to be technical grammar’s finest (and possibly only) contribution to the horror genre, employs the present continuous tense to imply that he literally dies mid sentence, as the sentence eerily continues nonetheless. "Yes;—no;—I have been sleeping—and now—now—I am dead."

Whilst M.Valdemar’s spirit seems to be preserved and contactable and his body refuses to decompose, he is trapped in a torturous nether region between life and death for months. In a beautifully awful conclusion, when the mesmerist finally releases him from the trance his body instantly putrifies and disintegrates.

So far, so wildly implausible. So why were people at the time so ready to be taken in by it?

Well, for the same reasons people were sucked in by the Blair Witch project: the relative infancy of the media format employed, the verisimilitude of the story itself and the experience of ‘The Fantastic’. In Poe’s case, all three of these things were balanced masterfully.

Unlike today, when medical reports not only have standardised formats but appear in very specific places, at the time at which Poe published, they would regularly appear in gentlemen’s magazines alongside news reports and works of fiction. Their format was not standardised particularly as far as the general public was aware. In exactly the same way that Blair Witch would exploit the infancy of internet years later, Poe exploited this by presenting the piece as a work of factual record both in style and placement.

The names in the piece, or rather lack of them, many of the names being reduced simply to a capital letter and a dash also add to the overall believability of the piece as it suggests those involved wish to reluctantly publicise the events but also wish to preserve their anonymity (unknown actors anyone?) The very number of ‘people involved’ is another factor. Poe is careful to underline the fact that there were numerous witnesses to the events recorded in the story, suggesting that any one of those who observed them could testify to their veracity, again increasing within the reader’s mind the likelihood of the report being true.

Moving past the obviously guiding title, ‘Facts’ and ‘Case’ being immediately suggestive to the reader that the story is not simply a gothic horror story but instead a factual account. Poe employs a number of other more subtle techniques to trick his readership. One such technique, and one which highlight’s Poe’s genius and influence, is his use of ‘The Fantastic’. Though it was only identified and named long after Poe’s death by Tsvertan Todorov, The Fantastic as a concept permeates Poe’s work and indeed can be identified in many of the most effective horror stories and films that followed.

The easiest way to think of ‘The Fantastic’ is a seesaw. On one side is ‘The Marvellous’ the possibility that events described are undoubtedly supernatural and caused by some agency beyond the realm of human understanding (file under this category ghosts, demons and things that go bump in the night). On the other side of the seesaw is The Uncanny, the possibility that the events, though weird, are explainable by means of a rational explanation. Freaky, but not necessarily supernatural. The Fantastic therefore, is the centre of the see saw, the pleasing point between the two extremes at which the reader is left doubtful, free to consider, to doubt and to decide for themselves whether what is being relayed is completely supernatural or can be rationally explained. Is is the uncertainty that creates ‘The Fantastic’.

Think back to The Blair Witch Project and the fact that no supernatural broom rider is ever actually seen. Whilst there are sounds and small tangible relics, nothing in the film is explicitly supernatural. The viewer is left to decide for themselves whether the goings on are attributable to the fabled witch or explainable. We as viewers experience ‘The Fantastic’. The exact same technique.

In M.Valdemar, Poe achieves this through his emphasis on techniques like schematisation, (breaking things down in systematic portions to make the proceedings seem official and clinical, again adding to the sense of verisimilitude) and chronology- recording accurately the times at which things happen as if there has been very close attention paid to these details. At the other extreme, he contrasts the very dry and businesslike manner in which the story is told with the use of poetic devices and enargia to create effects in the reader’s minds, with the detailed and deliberately evocative descriptions indicating the likelihood of an eyewitness account.

The use of sibilance and alliteration in describing Valdemar and his voice are disquietingly impactful as is the synaesthesia in the description of his disembodied voice as ‘gelationous’. Eewww. Incidentally, this was one of the very first ‘gross out’ moments in horror history, something which again lent the account an air of thorough truthfulness and influenced many later writers and directors drawn to the gory elements of horror (anyone who has ever read Lovecraft's Cool Air will note the striking similarities in the two tales and acknowledge that had they been alive at the same time, old H.P. would have owed Poe a pint or two in gratitude).

This was not the only time that Poe pulled the proverbial wool over the eyes of his readers. He was responsible for a number of other hoaxes and it seems was unusually adept at taking the public in with his fanciful tales. M. Valdemar still stands up as a classic of horror fiction and is well worth revisiting, firstly because of the massive and lasting influence it has had on the genre as a whole, but also, because it illustrates the interplay between doubt and belief that makes the best of horror so wonderfully affecting.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Posted from my blog with SteemPress : https://sinfullyvin.com/the-blair-witch-poe-ject-and-the-facts-in-the-case-mr-edgar/