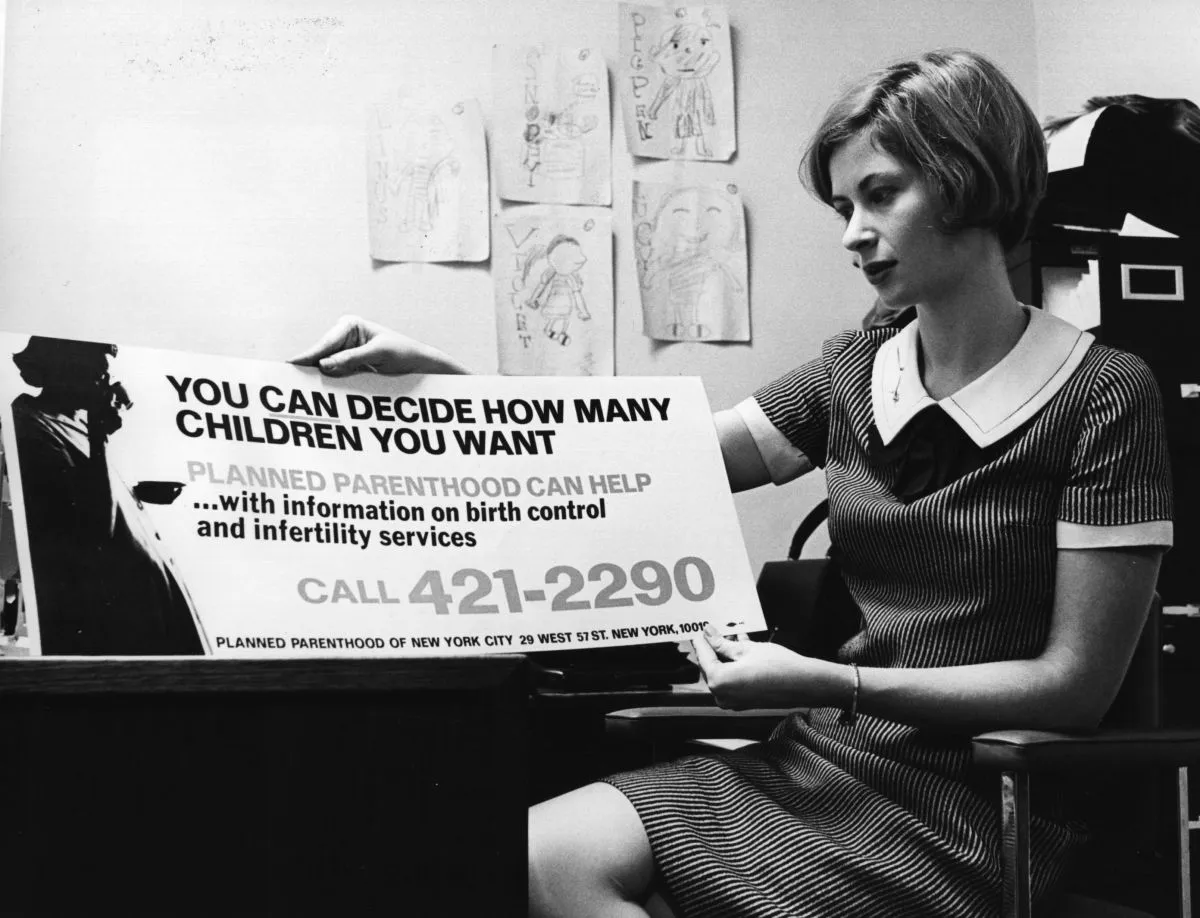

An employee of Planned Parenthood holds a sign about birth control to be displayed on New York City buses, 1967. (H. William Tetlow/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

For a variety of reasons, I don’t have kids. As a woman of a certain age, I’ve been conditioned to believe I must qualify that statement by assuring you it’s not that I’m some kid hater, or that I don’t think babies are cute. They are! (Okay, I also find them to be kind of disgusting.) But among my many reasons for not procreating is that kids grow up to be people, and life for most people on this overcrowded, overheated planet is hard, and getting harder.

Even before Donald Trump took office, I had often wondered: with terrorism, war, and genocide, with climate change rendering Earth increasingly less habitable, how do people feel optimistic enough about the future to bring new people into the world? Since the presidential election, the prospects for humanity seem only more dire. I’m hardly alone in this thinking; I can’t count how many times over the past year I’ve huddled among other non-breeders, wondering along with them in hushed tones, How on earth do people still want to have kids? I was surprised, at this bleak moment in American history, that I hadn’t seen any recent writing on the topic. Was it still too taboo to discuss not making babies, from any angle? Then this past week a few pieces caught my eye.

The one that spoke most directly to my doubts about perpetuating the human race, and its suffering, was “The Case for Not Being Born,” by Joshua Rothman at The New Yorker. Rothman interviews anti-natalist philosopher David Benatar, author of 2006’s Better Never to Have Been: the Harm of Coming Into Existence, and more recently, The Human Predicament: A Candid Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions. Rothman notes that Benatar makes no bones about his pessimism as it relates to humanity.

People, in short, say that life is good. Benatar believes that they are mistaken. “The quality of human life is, contrary to what many people think, actually quite appalling,” he writes, in “The Human Predicament.” He provides an escalating list of woes, designed to prove that even the lives of happy people are worse than they think. We’re almost always hungry or thirsty, he writes; when we’re not, we must go to the bathroom. We often experience “thermal discomfort”—we are too hot or too cold—or are tired and unable to nap. We suffer from itches, allergies, and colds, menstrual pains or hot flashes. Life is a procession of “frustrations and irritations”—waiting in traffic, standing in line, filling out forms. Forced to work, we often find our jobs exhausting; even “those who enjoy their work may have professional aspirations that remain unfulfilled.” Many lonely people remain single, while those who marry fight and divorce. “People want to be, look, and feel younger, and yet they age relentlessly. They have high hopes for their children and these are often thwarted when, for example, the children prove to be a disappointment in some way or other. When those close to us suffer, we suffer at the sight of it. When they die, we are bereft.”

While this isn’t how I always look at life, I believe Benatar makes some good points. (Not to mention I’ve endured three of the above mentioned hot flashes while writing this, and one’s optimism does tend to dip in those estrogen-depleted moments.)

Rothman’s piece reminded me of an essay we published here on Longreads a couple of years ago, “The Answer is Never,” by Sabine Heinlein. Like me, Heinlein often finds herself having to defend her preference for choosing to be childless: “One of the many differences between my husband and me is that he has never been forced to justify why he doesn’t want to have children. I, on the other hand, had to prepare my reasons from an early age.” She keeps a laundry list of reasons handy:

Over the years I tried out various, indisputable explanations: The world is bursting at the seams and there is little hope for the environment. According to the World Wildlife Fund, the Earth has lost half of its fauna in the last 40 years alone. The atmosphere is heating up due to greenhouse gases, and we are running out of resources at an alarming speed. Considering these facts, you don’t need an excuse not to have children, you need an excuse to have children! When I mention these statistics to people, they just nod. It’s as if their urge to procreate overrides their knowledge.

Is there any knowledge forbidding enough that it could potentially override such a primordial urge? In a devastating essay at New York magazine, “Every Parent Wants to Protect Their Child. I Never Got the Chance,” Jen Gann attests that there is. Gann writes about raising a son who suffers from cystic fibrosis, an incurable disease that will likely lead to his early death. The midwife practice neglected to warn her that she and her husband were carriers, and Gann writes that she would have chosen to terminate the pregnancy if they had.

The summer after Dudley was born, my sister-in-law came to visit; we were talking in the kitchen while he slept in the other room. “But,” she said, trying to figure out what it would mean to sue over a disease that can’t be prevented or fixed, “if you had known — ” I interrupted her, wanting to rush ahead but promptly bursting into tears when I said it: “There would be no Dudley.” I remember the look that crossed her face, how she nodded slowly and said, twice, “That’s a lot.”

What does it mean to fight for someone when what you’re fighting for is a missed chance at that person’s not existing?

The more I discuss the abortion I didn’t have, the easier that part gets to say aloud: I would have ended the pregnancy. I would have terminated. I would have had an abortion. That’s firmly in the past, and it is how I would have rearranged my actions, given all the information. It’s moving a piece of furniture from one place to another before anything can go wrong, the way we got rid of our wobbly side tables once Dudley learned to walk.

Finally, an essay that took me by surprise was “To Give a Name to It,” by Navneet Alang, at Hazlitt. Alang writes about a name that lingers in his mind: Tasneen, a name he had come up with for a child when he was in a relationship years ago, before the relationship ended, childlessly. It reminded me of the names I long ago came up with for children I might have had — Max and Chloe, after my paternal grandfather and maternal grandmother — during my first marriage, long before I learned I couldn’t have kids. This was actually good news, information that allowed me, finally, to feel permitted to override my conditioning and recognize my lack of desire for children, which was a tremendous relief.

Reading Alang’s essay, I realized that although I never brought those two people into the world, I had conceived of them in my mind. And somehow, in some small way, they still live there — two amorphous representatives of a thing called possibility.

A collection of baby names is like a taxonomy of hope, a kind of catechism for future lives scattered over the horizon. Yes, those lists are about the dream of a child to come, but for so many they are about repairing some wound, retrieving what has been lost to the years. All the same, there were certain conversations I could have with friends or the love of my life, and certain ones with family, and somehow they never quite met in the same way, or arrived at the same point. There is a difference between the impulse to name a child after a flapper from the Twenties, or search however futilely for some moniker that will repair historical trauma. Journeys were taken — across newly developed borders, off West in search of a better life, or to a new city for the next phase of a career — and some things have been rent that now cannot quite be stitched back together. One can only ever point one’s gaze toward the future, and project into that unfinished space a hope — that some future child will come and weave in words the thing that will, finally, suture the wound shut. One is forever left with ghosts: a yearning for a mythical wholeness that has slipped irretrievably behind the veil of history.

Yes, I know those ghosts, but not the yearning. I suppose I’m fortunate to not be bothered by either their absence in the physical realm, nor their vague presence somewhere deep in the recesses of my consciousness. Fortunate to no longer care what my lack of yearning might make people think of me.

Source:longreads.com