Tom King used to work for the CIA. Now he is DC Comics’ hottest writer.

was a bright summer day in Washington, D.C. I arrived at the meeting location, a pizzeria on Capitol Hill, about 15 minutes early. I was there to interview the comic book writer Tom King, who, in a previous life, spent seven years as a counterterrorism officer for the CIA. King is part of a long and thoroughly entertaining tradition of spies turned storytellers — (the racist) Ian Fleming, Stella Rimington, (the great) John le Carré, (the ultraparanoid) Charles McCarry, and, more recently, Jason Matthews — but he is the first whose primary medium is comics. I mean, as far as I can tell. We are talking about spies, after all.I was early because I was concerned about being prompt and professional, but also because I had seen Ronin too many times; I figured that if I was going to meet an ex-spy, I should get there first, get the lay of the land. I did a walkthrough of the restaurant, and once I was certain I’d arrived first, I sat outside on the patio, at the table closest the door. I spent the next few minutes on my laptop, checking my notes and scanning the faces of the people passing by. I glanced back toward the entrance, and there was King, leaning against the doorframe, scrolling through his phone.Tom King, 37, is of average height and dad-ish build, with close-cropped hair and a few days of stubble. He looks like a slightly more combat-ready Joss Whedon. King was wearing a faded blue T-shirt depicting the classic Bronze Age Batman logo: the bat cape spread to resemble the ragged silhouette of a pair of chiropteran wings, with Bruce Wayne’s becowled visage looking out and yellow block letters spelling “BATMAN” filling the interior space.“I wanted to make sure you recognized me,” he said as we shook hands. At the time, King was one issue into his tenure as the writer of DC Comics’ Batman, and, thus now the guardian of one of pop culture’s most iconic characters.In addition to Batman, which ships twice a month, he pens The Vision(Marvel) and The Sheriff of Babylon (Vertigo), a fractured, brutal, Tolstoyan noir set in post-invasion Iraq that draws heavily on King’s experiences as a member of the Agency.King’s ascent from the CIA to unemployed writer to underemployed writer to rookie comic book author to creative mind behind two of the best ongoing titles in comics and writer of freaking Batman has been shockingly abrupt.We haggled momentarily over who was going to buy whom a slice of pizza. King shut down the debate by saying, in the tone of a guy whose slot machine just paid off on his last token, “Batman number 1 is selling really well!”

King was raised in Los Angeles by a single mother who worked in the lower rungs of the entertainment industry. His father wasn’t around. “I was your typical nerd,” he said. “I couldn’t throw a ball. I couldn’t run. Fat kid, bullied, all that stuff. But the one thing I could do real well was sit in the corner and read something. I don’t know what it is about comics, but when you read them you wanna write them.”While at Columbia in the late ’90s, King interned at the DC Comics imprint Vertigo (where his duties included photocopying pages of Preacher) and Marvel (where he was legendary X-Men writer Chris Claremont’s assistant). It was the darkest period of the industry’s modern history. Earlier in the decade, headlines trumpeting eye-popping auction prices (“Holy Record Breaker,” exclaimed The New York Times in 1991) for blue-chip issues drew speculators looking for a hedge against the recession. The Big Two comic book houses — DC and Marvel — responded as collectible industries, from Beanie Babies tobaseball cards, always have: pumping product into the overheated market. In retrospect, a crash was inevitable. At Marvel, various other mitigating factors — too many titles shipped too far behind schedule, a poorly received, line-wide reboot/retcon, weak leadership, and the death of beloved editor Mark Gruenwald — resulted in losses of more than $400 million in the fourth quarter of 1996 alone. DC, meanwhile, attempted to capitalize on the speculative boom by creating headline moments — “The Death of Superman,”Batman: Knightfall — transparently designed to become collectible. The result was like an industrywide sugar high, with twitchy excitement followed quickly by nagging feelings of emptiness. By the mid-’90s, sales of new comics had declined by 70 percent, and nine out 10 comic book stores had gone out of business.The dire state of the business convinced King to reconsider his authorial aspirations: “People told me at that time, ‘Yeah, this whole medium has two months left.’” He switched tracks. By the summer of 2001, King was in Washington, D.C., working at the Justice Department. He was in D.C. on 9/11, and he applied to the CIA soon after.

Iasked King how long after he applied to the Agency that he received a response.King speaks in a syncopated rhythm, like a jazz drummer warming up on the snare, and with the casual manner of a reformed nerd who’s comfortable in his own skin. He has a disarming way of framing his various experiences as, um, a spy, into an extended run of Forrest Gumpian fortune, like he just kind of aw-shucksed his way into Langley and, later, Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Well, I can’t talk too much about the process. But my first recruitment meeting was like, I swear to God, ‘Men in Black.’I sat down, [and] the dude on my left was like a special forces dude, could kill me at any second with one of his eyebrows. And then the dude on my right had three PhDs and was like, ‘Yeah, my Arabic is not as good as my Farsi, but you know, I’m catching up.’ I was sitting there like, ‘Uhh … I like Captain America …’ But I kept going up the process like, ‘Are you sure? All right, I’ll go to the next stage.’”

A reality shift occurs whenever a person moves beyond a rarefied entity’s stage-crafted mystique and becomes an employee of that entity — whether it’s a toy store, Goldman Sachs, or an intelligence service. Sure, the CIA is an elite organization depicted in countless works of fiction, and it has, in reality,overthrown governments, carried out assassinations, tortured people, and engaged in wide-ranging mind-control experiments using doses of LSD. But it’s also a workplace. Cigarette burns on the couch, soda stains on the carpet in the lounge, coffee breath, busy work. Right?“I think it’s like any work environment,” said King. “I think the thing that’s most surprising is that the young people in their 20s do all the work, and that the people who are older are doing a lot of management of HR and stuff like that. Like, in the movies, you always see the head of CIA, and he’s down in the street, doing all these clandestine meetings and stuff. No, that’s like seven levels higher up from what’s actually being done.” He continues: “I remember I worked in the ops room, you know, like Tom Clancy’s ops room. It was during the Iraq War. ‘This is going to be amazing, I’m working in an ops room.’ And it’s mostly just dudes watching CNN trying to get through the night. The work gets done, but it’s not what you think it is.”King considers his work at the CIA to be the best job he’s ever had. If not for his growing family (he and his wife have three children), he would have stayed on. “I couldn’t really be the father I wanted to be and the operations officer I wanted to be at the same time,” he said. “People do it, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. The thing I most loved about being in the CIA was being in war zones and being overseas. My wife and I spent the first four years of our marriage apart about half the time. When you have a kid, it’s a whole different thing, right? I grew up without a dad, and I just didn’t want to do that to my kids.”By writing at night after his kids went to sleep, King was able to finish a novel,A Once Crowded Sky. It’s about superheroes who give up their powers to save their city. Touchstone published it in 2012, and, though it was reviewed mostly kindly and occasionally glowingly, no one bought it. But it did help open doors.Writing comics is about hitting deadlines, and here was a guy who banged out a 300-page book in his spare time. King cold-emailed editors at DC and Marvel. That, somewhat meanderingly, led in 2013 to his comics debut, in the anthology Time Warp: an eight-page story about time travel titled “It’s Full of Demons,” illustrated by Tom Fowler. The issue, published by the DC adult-oriented line Vertigo Comics, also featured stories by Damon Lindelof (television’s Lost, The Leftovers), Gail Simone (Batgirl), and Peter Milligan (X-Statix). Just three years later, King has numerous credits to his name, is the writer of the best ongoing title at either Marvel or DC, has turned his experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan into a bracing and brutal war comic that King says is being developed for television, and has just signed an exclusive deal with DC to write Batman.“That kind of 0 to 60 is unheard of in comics,” comics journalist David Harper, proprietor of the blog Sktchd, told me over email. “Normally the path is pay your dues, pay your dues some more, write some super wack DC or Marvel comic, write something slightly less wack, get a good book later. He just skipped straight to the top, even though in a lot of ways he’s probably still learning how to write comics.”

King’s work on Marvel Comics’ Vision announced him as a truly fresh voice in comics, a writer capable of discovering new dimensions in a decades-old character by reframing our understanding of him within the current cultural moment. Vision no. 1 was released in November 2015 and was immediately a critical hit. Ta-Nehisi Coates declaredit “the best comic going right now.”“Vision number one, just that one issue, changed everything,” King said.King’s innovation was to jettison the android-wearing-a-cardigan sight gag that had come to define the character, and instead imagine Vision as a suburban, existential tragedy. It’s John Cheever meets A.I. King was worried that Marvel would find his pitch too dull. “I ran it by a buddy of mine and he was like, ‘That sounds really boring, man.’” It isn’t. The book’s quiet moments are its best.

‘Vision’ Issue no. 1 (Marvel)

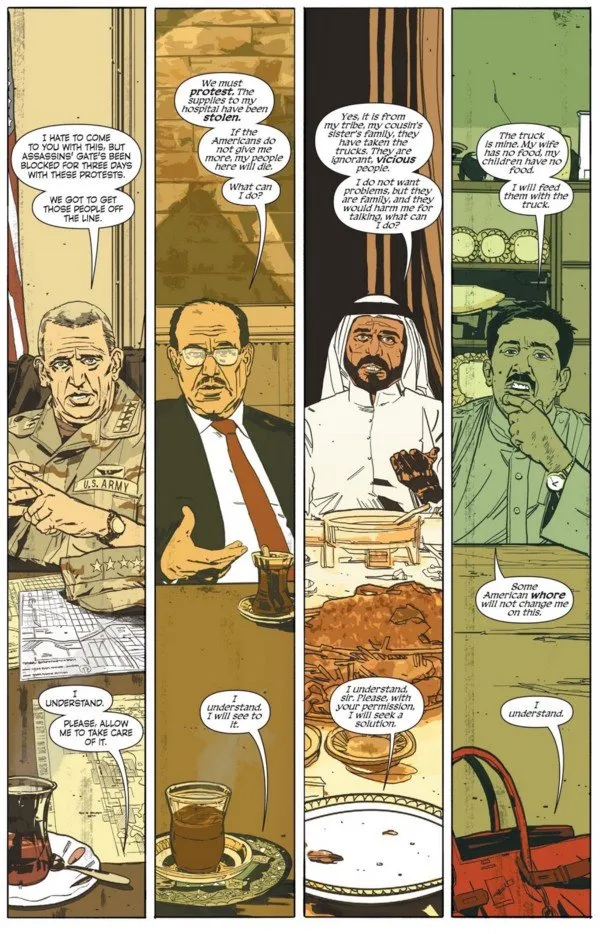

In a strange way, the suburban angst of Vision is of a piece with King’s Vertigo title, The Sheriff of Babylon. Brutal where Vision is brooding, Sheriff is the stateside“go out and shop” obverse to the post-invasion chaos of 2004 Iraq.“I got there in February 2004. We invaded March ’03, so this is about a year after that,” King recalled. “When I got there we were winning the war, and by the time I left we were losing it. So much of the Iraq War was bullshitting. Saddam was bullshitting us about having weapons and we were bullshitting him about being able to take him out easy. The government was bullshitting the people about what it would be like and the people were bullshitting the government. Everyone was lying to each other, and then that’s what the whole series is about.”

‘The Sheriff of Babylon’ Issue no. 1 (Vertigo)

The Sheriff of Babylon is skeptical about America’s role in the conflict and unsparing in its depictions of violence and torture. The result is a noir that unfurls in a confounding media res, like walking into the middle of a story that’s been going on for centuries. With Sheriff, King expects a lot from his readers. There are no editorial text boxes explaining the differences between Sunni and Shia and Kurd, no mini lessons on the unintended consequences of de-Baathification. There are references to the Mahmudiyah case and Abu Ghraib, and depictions of “enhanced interrogation” techniques. King doesn’t, and probably can’t (everything he writes about the CIA must be cleared by the Agency), say how much of what happens in Sheriff is based on his experiences, but it is clearly his most personal work.“[Writing Sheriff] was not how I wanted to spend my days, being back in those memories,” he said. “PTSD is a weird thing where it can do two things to you and do it simultaneously. They always show one side of it on TV. You know, ‘I’m so ashamed of what I did,’ or, ‘Something bad happened to me. It brings back these memories of fear.’ But PTSD also does this other thing where it’s, like, when I was there and I was in danger, but I was also happy because I had a simple goal. Now I’m back here and I’m with my family and I don’t know what’s good and what’s bad. I feel bad and guilty at the same time, like I want to be there and I don’t want to be there.”

InFebruary, DC Comics signed King to an exclusive contract and announced him as the latest writer of Batman, the jewel in the company’s intellectual property crown. It’s a huge responsibility. Compared to writing Batman, King’s other jobs “are easy comics. [Batman is] the hard one.” King’s Batman launched in June.“Batman is its own beast,” King said. “It’s weird. I write these very thinky comics where there’s no hero. Sheriff doesn’t have a hero; no one at the end of it is gonna be like: ‘Yay! I triumphed and solved terrorism!’ Vision, at the end, it’s set up as a tragedy and I know how it ends, it’s tragic. What Batman is, is a story about a hero triumphant. The best thing Batman can do with me is to be a good comic that takes people a little bit outside of their day, where they can read and be like, ‘Holy shit!’ That gives you a jolt of pleasure. I’m not trying with Batman to be like, ‘OK, here I want to comment on the world.’ I want to make Die Hard.”Four issues in, it’s hard to say whether King has yippie-kay-ya’d the Caped Crusader. But he’s off to a promising start.King and I walked out of the restaurant into the afternoon sunshine, talking about movies. He mentioned The Searchers, the John Ford–John Wayne classic about a murderous ex-Confederate on a mission to rescue his niece from an Indian tribe that has kidnapped her. I asked King whether he thought The Searchers was a racist movie or a movie about a racist dude.“It’s both of those things. That’s what makes that transcendent. The idea that if you sit back and think about it, he’s a horrible person. But you’re still like, ‘I want to root for John Wayne, and I want him to win.’”I mentioned having read an interview in which King referred to Batman as being “psychotic and inspiring.” I asked if the dichotomy of The Searchers is what he’s going for with Batman.“We’ll see, we’ll see,” he said.He crossed Pennsylvania Avenue and disappeared into the crowd.