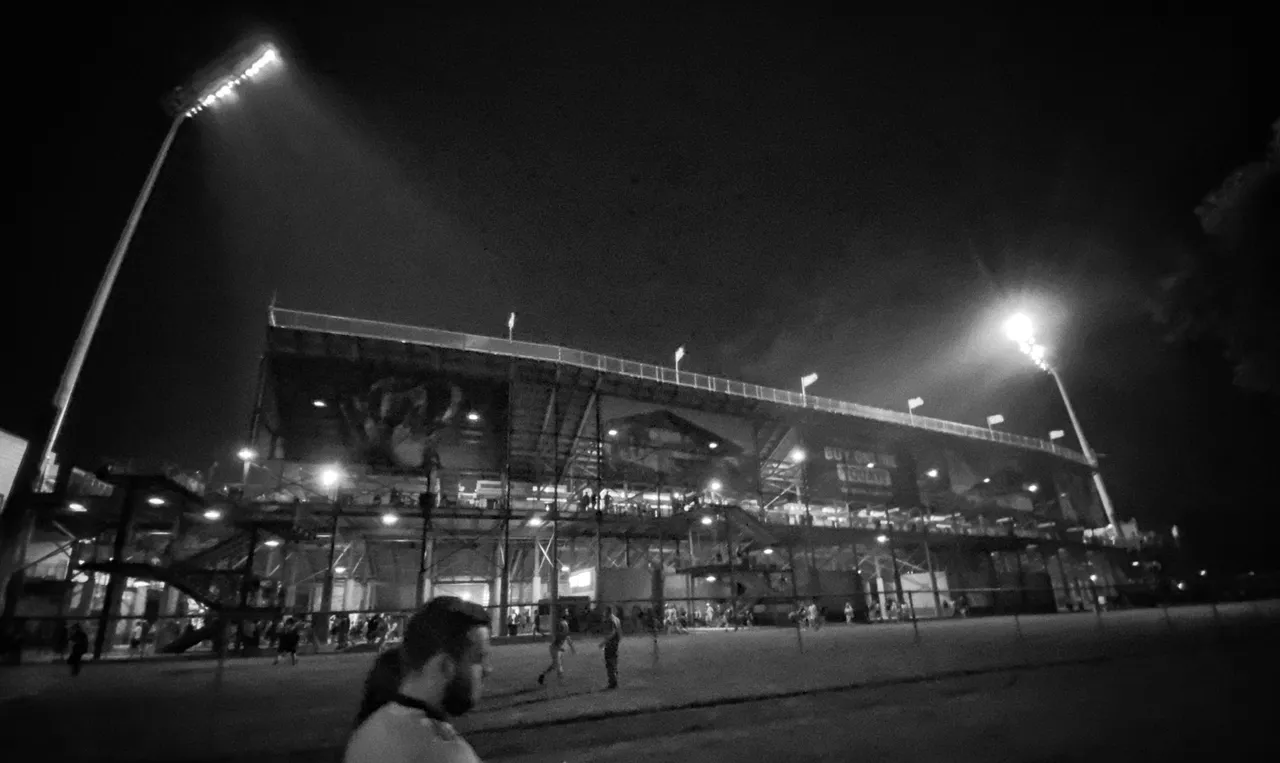

Whenever I reach Historic Crew Stadium (Crew Stadium from here on out) on match day, and more exactly, when I’m standing in the parking lots—those barrier wastes that wall the weak-willed off from the paradise at its center—I almost always end up marveling at the magnitude and diversity of the Crew family. I get freshly astonished by the sheer number of canopies and tailgates dotted across the landscape, the tally of the ones I recognize dwarfed by the number of the ones I don’t. I think about how each canopy and person and family has a distinctive, individual story of what the Crew mean to them, and why, and it staggers me.

As I cross the five-million-dollar pavement to the tailgates, there are always more faces there that I don’t know than the ones I do. I marvel again at all of their stories, and think about how far the experience of being a Crew fan extends beyond me, beyond the experience of anyone I know. I think about how many stories I don’t know about why the Crew matter so much, why Crew Stadium matters so much.

On June 19th, the afternoon of the final game at HCS, as I wandered through the parking lots toward MegaTailgate, I was struck not just by the endlessness of the other stories, but by the variety of my own. How different the person wearing my name has been across my twenty years of going to Crew Stadium for games.

The first time I visited, I was eleven; the stadium was two years old. So much of what made up my life no longer exists in my memory with any clarity—I can’t remember what car we drove in, I can’t remember what size shoes I pounded on the echoing aluminum, but I remember the feeling. I’d never seen anything like professional soccer. I had certainly never seen professional soccer—not outside of photos in books and newspapers. The Crew, to that point, had existed for me entirely in print and on the radio. Seeing it in person was intoxicating, but it was more than just a dazzling spectacle. It was a world of pageantry, precision, and professionalism beyond anything I had experienced or aspired to. What I felt was something that lay between ambition and awe.

More than my impression from visiting, though, Crew Stadium represented a way to be proud of Columbus. Crew Stadium was a reason my city was on the map for American soccer, even if American soccer was still looking for its own place. But when the future of professional soccer in America hung in the balance in 2001, I clung to the idea that Crew Stadium was a tangible, physical reminder of soccer’s viability and its best and only path forward with Americans. I didn’t know or didn’t fully consider that the danger to the league was a danger to Crew Stadium, a question hovering over the Expo Center barrens—how would it end for Crew Stadium? Foundation or folly? .

In the twenty years between my first visit and my last, I’ve been in Crew Stadium as a contest winner, as a son, as a boy scout, a church kid, a college student, a college chaperone, a friend, and a father. On my first-ever visit, I sat in the sections that would one day become Nordecke. Over the course of twenty years, I’ve watched games from every part of the stadium (including, on one discombobulating occasion, one of the suites) except the club seats and those directors’ chairs on the sideline. And, in the interest of completeness, I should note that I never got to sit in the Best Seats in the HouseTM.

I’ve come to Crew Stadium in seasons of national tragedy, and in moments of personal loss and struggle. I’ve been crushed, been enraged, been bored, been distracted, been dazzled, inspired, and transcendentally ecstatic in Crew Stadium.

Starting with that first just-a-little-chilly loss to the San Jose Earthquakes in the 2001 playoffs, I’ve spent as much of my life shivering in Crew Stadium as anywhere. I’ve been to too many games where “build a bonfire” started to sound less like a sneer, and more like a plea.

The most transcendent slice of pizza I’ve ever tasted was a Dominos pepperoni pizza from a Crew Stadium concessions stand—my dad swallowing his frugality in an effort to buy us time before the hypothermia set in.

I’ve spent as much of the lifespan of my vocal cords in those bleachers as I have anywhere else. I screamed myself hoarse with the ecstasy of triumph when Justin Meram scored within the first nine seconds against the Red Bulls. I lost my voice within the first ten minutes of MLS Cup 2015, raving like a madman in the east side nosebleeds, calling down thunder, fire and judgment on the Timbers, on the Refs, on anyone who was handy.

Brent, a friend I met through Crew Twitter, responded to my Twitter request for fans’ thoughts about the last game at Crew Stadium. His first game, it turns out, came before mine. It was 1999, so early in his life that he can’t remember it anymore, but he remembers 2008. He was older then. Old enough to fall in love with what he saw, and to drag his family back to the stadium over and over with a youthful force of will. At the time, he didn’t know how early in life his story connected to the stadium. Nor how deep the connection has become,

“Until this week, I never really realized just how much time I've actually spent there,” he tells me, “how many of the people in my life are because of that place.”

How many times have you sung in a choir? How many times have you hugged a stranger? How many times have the drums of anywhere rung out to call you home? How many miles have you walked, after all, between parking spots, and tailgates, to fall down at that door? How many hours of your life have you spent standing in rain, in snow, in ice and in wind at Crew Stadium? How many have you spent anywhere else?

How many ways has your hometown changed around you in the twenty-two years Crew Stadium has been standing sentinel on the fairgrounds? How many pairs of shoes have you rung against the bleachers? How many clouds have gathered against a purple sunset and ridden the gale across Crew Stadium? How many times have Crew fans been forced to try to look ahead and ask - when it all ends for Crew Stadium, what will its legacy be?

What is its legacy, now? “Sure, there was hardship, pain, and grief,” says Brent, “But ultimately those moments just make the good times that much brighter. I wasn't ready to leave.”

Like me, Blaine, who also reached out to me on Twitter, remembers being proud that the first soccer-specific professional stadium was in Ohio. He remembers sensing the importance of the stadium, even from a distance. And even though it’s time, he says that most of all, he’s glad it’s not being torn down,

“There is too much history within Historic Crew Stadium to turn it all into scrap. Personally I very much like the idea of turning it into a facility for the community—even more so if it means passing the beautiful game onto the next generation.”

But it isn’t just passing on the beautiful game. It isn’t just what it means to the community. It’s also what it means to people for whom no other stadium can mean quite the same thing. A part of the legacy of Crew Stadium is the people who had their places inside of it, but are not here to see the end.

“I’ve been thinking about those who won’t ‘move on’ to the new stadium,” Bruna wrote to me on Twitter, early Monday morning, “Kirk Urso’s family for example or all of those whose family member or friend celebrated at games and made memories at the stadium but are now gone. For those people the new stadium will really never be the same.”

I can’t speak for those folks, and I won’t. Their thoughts, their experiences, and their sorrows are their own. They are a part of who we all are as Crew fans, as people who gather to sing and cheer for the team, and they deserve our acknowledgement.

Finally, twenty years after I clung to the existence of Crew Stadium as evidence that the league had a future, we know the answer to the question - how does it all end for Crew Stadium?

When I get to the parking lots on June 19, we’re running late and I’m haunted by the feeling that I’m missing out on something—an experience, a conversation, the right angle on the right part of the stadium—to give meaning to this whole last-game experience. I’m not crying, and I don’t feel like crying yet. Maybe I’m here looking for something to make me cry.

Megatailgate is dissolving, and folks are heading in, but I walk through the middle of it anyway, luxuriating in the buzz, trying to take mental notes of every image, every unexpected meeting with a friend.

The parking lot, the gate, the plaza, the music, the food, the seats—everything is supercharged, but everything is familiar. It all feels like it’s changed less over the past twenty years than I have.

We get to our seats with twenty minutes left until kickoff. Already, the people are singing. The sky is bright and hot, and I wonder if I’ll come home with a sunburn.

For the whole first half, the chanting keeps its steam up. Together we are a locomotive charging off the tracks, barreling through the stadium, happy for any reason to cheer, or just make a lot of noise.

A disallowed goal sparks a shower of happy boos. The booing is cheerful because tonight, we can tell how this will all end. We can sense what’s coming in the air, and no eleven-man memorial to Mrs. O'Leary's cow with the heavy first touch can push back the inevitable.

And there it is. A goal. A wash of sound. An ear-splitting roar. Beer sprays. Water sprays. Fire belches out over Crew Stadium, and down below, we’re dancing.

We’re chanting too much about Chicago and how much they suck. Sure, once upon a time Chicago were Seattle who were Atlanta who are now LAFC. But like all MLS super teams, they come, they strike their terror, and in time, they turn up at Crew Stadium to pay their respects. Why worry about them when we’re having a night for ourselves? A night to remember all the runny noses and frozen toes and heartbreaks and euphorias we’ve brought in our little bodies to this rattling metal cathedral with its otherworldly field. Forget Chicago.

Another goal. Another staggering dance under the smoke and flags. Fire in the sky. On the Upper 90 patio, where Zack (who later describes the scene to me via Twitter messages) is standing with friends, caught in a strained standoff between fans accustomed to standing at the rails with their drinks, and security staff who’ve been instructed to rope off the area directly next to the railing, some folks bursts through the rope line in the chaos after the second goal, and makes it to the railing, where they want to be.

As the chaos subsides, the crowd is ushered back inside their rope barrier, but the spell is broken and the mood has changed. It isn’t long before good vibes prevail, and there’s room for everyone at the railing.

Back in Nordecke, I leave at halftime to find more water for my pregnant wife. In the halftime crowds, I see a few familiar faces. They don’t see me or if they do, say nothing, and neither do I. They’re walking with their families—biological, adopted, and informal—laughing at jokes, grinning at their kids' antics, or just smiling because this is a moment for smiling.

And I’m smiling with my family, too. With my wife, and with the friends I knew before the Crew made hundreds of strangers into new friends. We’re together, we’re cheering for the Crew, we’re remembering how it feels to be together in this place.

Joy carries us through a second-half lull. The game gets listless; the players get tired. Kevin Molino makes his debut, and it turns out he’s...tired. Later, people all over the stadium start waving their phones in the air like it’s the encore at a Journey show. We never stopped believing. We still won’t stop believing.

The phones mostly go back into pockets, because realistically, there’s only so long a person with a healthy sense of shame can wave a phone. As the clock winds down on Crew Stadium, the energy gathers again. It builds into thunder. The chants come thicker, faster, louder. The ragged voices rise again. Twice as tired; just as loud.

The game is over, and the chanting goes on and on and on. How can this be the last game at Crew stadium? How can this be the end?

The players assemble, their families assemble, we’re all together in the corner, letting the curtain come down gently, singing “Wise men say…”

And then the chanting goes on and on. Players are dancing, or running to Nordecke. Pedro Santos’ son peels off the crowd and heads for goal with the ball at his feet. He puts it in, and the crowd goes wild.

The details get fuzzier. Frankie emerges from the crowd on the field and hypes us up until we’re roaring again as he pounds his heart. A video plays, and only a few people watch, some of the time. We’ll look it up online.

After the fireworks, I let one wave of fans hit the exits before I go, and for a moment, I stand beside the stairs, struggling with a feeling of incompleteness, of needing to stay to see the proper end. To be there when the credits roll.

But I don’t like to prolong a goodbye without knowing what I’m waiting for, so I go, still fighting that same feeling from the afternoon, still looking for a reason to cry. We fumble our way into the second wave of people heading up the bleachers and around the upper deck. It feels familiar, like we’ll be here next time, too. As we stream to the stairs, I take out my phone and start taking pictures. I’ve never taken pictures of this before—first-timers, contest-winners, parents, kids, players, fans, singers, drummers, long-timers—trudging back into our full-time roles and identities.

As I walk, all the ways that I’ve seen Crew Stadium, from dizzying, otherworldly paradise to an avatar of a man’s neglect for all the things he was charged with stewarding, to a tired friend, and all the different roles I’ve played in those stands, all the joy and the regret and the frustration and anger and elation, all the snot and the sweat and the sunburn and the sore throats, swim in front of my eyes. And I think again about each person walking with me carrying their own snapshots of themselves as they have been at Crew Stadium.

On the Monday after the last game, I ask Brent what he meant when he said he wasn’t ready to leave, whether there was something unfinished about it all for him, and he says no, not really, “If this was going to be a thing that had to happen, I think this feels like the best way/time to do it. It's just hard to say goodbye to something that's been so prominent.”

I agree.

For twenty-two years, we’ve streamed in our thousands through those parking lots to Crew Stadium, captured by an individual visions of the magic that waits for us in the tailgates and in the stadium. Each of us on a path unique to ourselves, a series of identities and expressions playing out on the canvas of this cathedral.

Until the week of the final game, I’d never thought much about how my memories of games contain capsules of my life, and personal history. Because when I think about Crew Stadium, I don’t think of myself as an 11-year-old first-time fan, inspired and overwhelmed and cold, nor as a father trying to shield my toddler from blinding sunlight and sweltering heat, nor as any of the other roles I’ve played within Crew Stadium. I’m not an Upper Deck person, a Lower Deck person, a South End person, or a Nordecke person.

Because while we’re there—whether we wear black and gold and chant and sing in the host of thousands and scream and pound our feet and clap our hands numb among the flags and smoke, or sit silent in the upper deck, or crowd the ropes in the Upper 90; whether we’re screaming in frenzied exultation for Brian McBride or Chad Marshall or Justin Meram or Harrison Afful or Lucas Zelarayán, or raging in the stands against a man who wishes us harm—at Crew Stadium, we’re Crew fans. And Crew Stadium is our home.

Like any home, there comes a time to leave, a time when it’s no longer the home we need. Like any home we leave, we leave some of ourselves behind. But what made Crew Stadium great, what makes it great still, standing alone in the corner of the fairgrounds in the brutal majesty of its architecture and the unrepentant utilitarianism of its construction, is the family it welcomed and nurtured and (kind of) protected.

Our new home will become great not just because of its architecture and the craft of its construction. It will be great because it will open its doors to people who enter as first-timers, contest-winners, children, parents, boyfriends, girlfriends, partners, sponsors and reluctant taggers-along. But once those folks are inside, they’ll only remember themselves as Crew fans. We are all Crew fans, and we are all home.