When I was in elementary school, at perhaps age eight, I had a friend who shall be called 'Bob' for the purposes of this story. Bob and I would meet up on weekends and conduct little science experiments. We would do things like make invisible ink from lemon juice or build simple electrical circuits to see how they worked.

One day, I learned about surface tension, and could not wait to tell my friend about this magical force. But when I went over to Bob's house, he totally didn't believe me that surface tension could keep a metal jar lid afloat in a pool of water even if there was a hole punched through the center of the lid.

This being the days before google was at our fingertips to instantly resolve such disputes, I insisted that surface tension did indeed have this power, and we argued about it. Eventually, Bob's dad intervened, and - confident that his son knew better than I did - suggested that a simple experiment would settle the matter and prove me wrong.

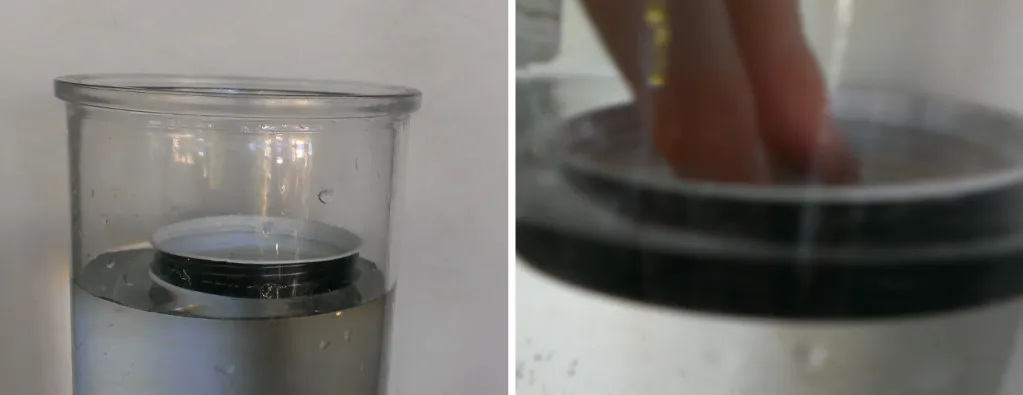

We filled up the kitchen sink with water, found a suitable lid from a used glass jar, punched a small hole in the center of this with a hammer-and-nail, and set the lid atop the water in the sink. And it floated. Obviously. Because of surface tension. For half an hour.

The observable fact of this, strangely enough, did not dissuade Bob or his father from their position. Rather than admit that the stance they had taken was incorrect, they decided that, because the lid didn't weigh very much, it was merely taking a long time to sink; they remained certain that it would eventually fill with water because of the hole and fall to the bottom of the pool.

To hurry this theoretically inevitable process along, Bob's dad removed the lid from the water, punched several additional holes through it, and placed it back on the water's surface.

Again, it did not sink. It floated. Because of surface tension.

After it floated there for a minute or two, I was sure that my friend and his father would concede and admit that I had been right. But that's not what happened. Instead, Bob's father said that it was still just taking a long time for the jar lid to sink, and pushed the lid underwater with his fingers to "help it along."

This, of course, invalidated our experiment by breaking the surface tension that kept the thing afloat. When the lid therefore sank, Bob's dad told me that this experiment had disproven my claim, and 'scientifically proven' that his son had been right.

* * * *

As a somewhat nerdy eight year old boy, I was outraged by this grievous violation of the scientific method's rules, and could not make sense of such a blatant denial of reality. These were, after all, otherwise reasonable people. My friend Bob shared my own interest in discovering nature's rules, and his dad was a staunch 'rational' who did some sort of engineering as a job. They were not dullards. Yet they both maintained that my claims about surface tension had been undeniably falsified by the experiment that Bob's dad had clearly rendered invalid.

It was a fascinating event that did not make any sense to me until many years later - whereupon I began to imagine that my friend's father had been consciously unaware of his actions and the way that these actions had invalidated the results of our little childhood experiment.

In hindsight, it seems likely that Bob's father had an unconscious emotional stake in his son winning our argument, and went so far as to physically manipulate events in service to this motivation, while Bob simply failed to attend to the observable information that would have proven his position incorrect - electing, instead, to defer to his dad's perceived expertise in all things worldly. Although this may have prevented my friend from learning about surface tension on that day, it ended up demonstrating for me some extremely important things having to do with people in relation to the procedures on which the scientific method's effectiveness is contingent.

Specifically, if someone is unconsciously motivated to achieve a given result in an experiment, and if that person also has the opportunity to manipulate experimental conditions towards this result, then - perhaps unbeknownst even to them- they may engage in such manipulation while remaining convinced that they have not done so.

The most remarkable thing about this particular event was in how clearly it demonstrated the potential for unconscious motivations to undermine the value of the scientific method itself. Although this may not carry particularly comforting implications for the soundness of the 'truths' on which our societal narratives about objective reality presently rest, it does provide an opportunity to somewhat demystify a problematic phenomenon in scientific research dubbed the 'decline effect' in a 2010 New Yorker article titled 'The Truth Wears Off'.

* * * *

The Decline Effect: Does Truth Decompose?

"It’s as if our facts were losing their truth: claims that have been enshrined in textbooks are suddenly unprovable. This phenomenon doesn’t yet have an official name, but it’s occurring across a wide range of fields, from psychology to ecology. In the field of medicine, the phenomenon seems extremely widespread..."

(Quote from: Jonah Lehrer, The Truth Wears Off, The New Yorker, December 13, 2010)

Here is how the decline effect shows up: First, researchers conduct an experiment, obtain a significant result, and publish their findings. Then, the experiment is replicated again and again. The more times such an experiment is repeated, the less pronounced its results tend to become. No matter how robust the initial experiment may have been, or how carefully this experiment is replicated, its results change over time, declining in significance, until they eventually become trivial.

The challenge is that such findings are robust to begin with. They do appear to solve problems, and may prove their value in all sorts of ways.

But this robustness is impermanent. Eventually, an experiment can no longer produce the result that it once did, and for reasons that are not easily seen or understood.

Problematically, this leads some researchers to conclude that "for most study designs and settings, it is more likely for a research claim to be false than true. Moreover, for many current scientific fields, claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias.". (This is something that even 'respectable' journals are beginning to look at.)

I do not believe that this suggests that the scientific method is a sham, nor do I imagine that most researchers intentionally skew their results. These thing are obviously not the case. Yet the measurable effectiveness of - for example - medicine does appear to be contingent on prevailing biases; perhaps even moreso than on some objective, mechanical truth.

This raises questions with potentially far reaching implications. When such questions are raised in too direct or explicit a manner, they seem to trigger a noticeable amplification of our tendencies towards false certainty, epistemological insularity, and ideological zealotry. As our computing technology gives us larger and larger pools of verifiable 'facts' to selectively query with our biases, and as it becomes easier and easier to restrict our communications with others to people that share our own, 'personal' beliefs, these tendencies may become increasingly pronounced in ways that we, ourselves, are not typically in a position to notice.

To my way of thinking, here is where things get interesting.

If a research finding - which is to say an experimentally verifiable truth claim - is an accurate measure of prevailing biases, and if such prevailing biases are variable across several distinct and perhaps epistemologically insulated locations within our broader psychosocial ecology, then experimentally verifiable truth may appear comparably variable, rendering the observable world far less objective than we believe it to be.

The 'world' itself might be a place of objective mechanical certainty, but we can neither see nor measure this except through the lens of a biased human perspectives. While this may challenge standard assumptions about scientific research, it does so without necessarily challenging the validity of the results that such research obtains. It merely constrains the application of findings to select, qualified domains of our psychosocial ecology - which is exactly what good scientists have been doing all along.

The point is that the variability of verifiable truth may impossible to eliminate, because it is impossible to remove our biases from the equation in many circumstances. Although this notion may feel heretical to reductive materialists, it is a useful idea with far reaching implications - perhaps opening up fields of study that have been impossible to explore because they challenge the prevailing biases of the scientific community (and those to whom this community is beholden).