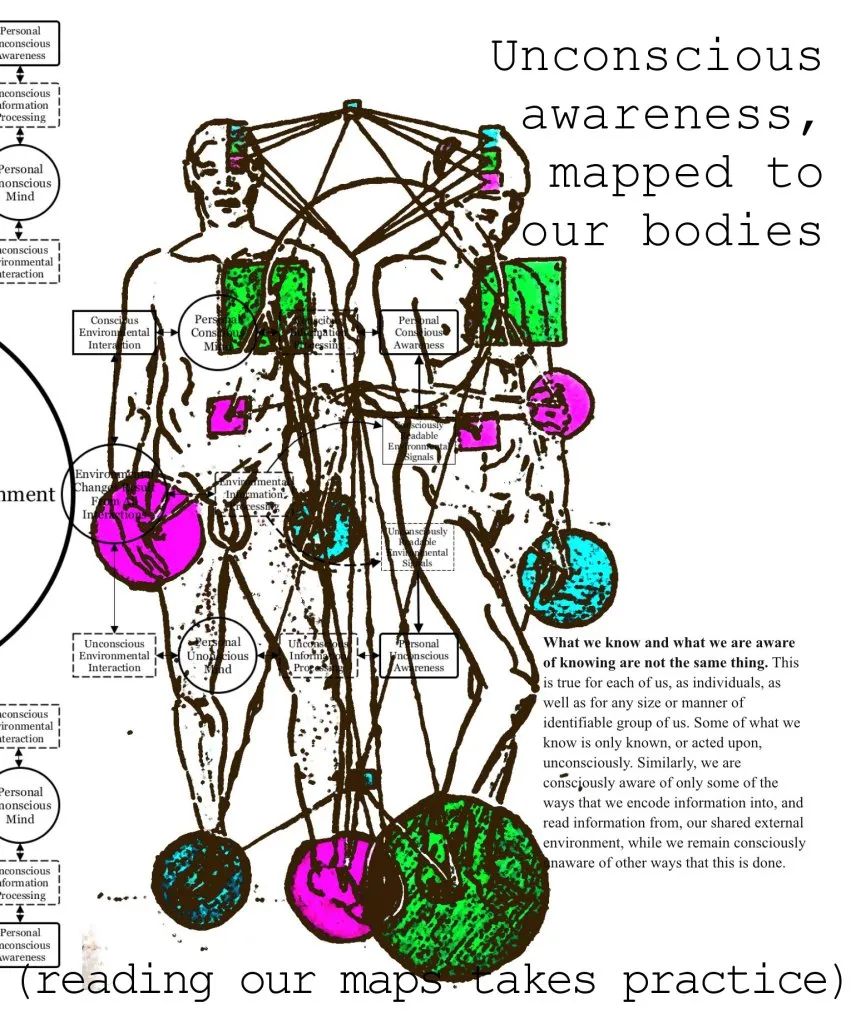

Both conscious and unconscious awareness is written into and read from our bodies in a variety of ways. Whether or not we notice it, our interaction with this information has a strong influence on thinking, behavior, and the experience of life in general. Such interaction is often conceptualized as memory. But human memory is not as simple as we might imagine.

What happens when we remember? Although we imagine that we recall the past, it is probably more accurate to say that we associatively reconstruct the past in the present, and then interact with this reconstruction.

According to a consistently validated model, memory is fundamentally associative. Categorical memory is an extension of this, as our categorical structures themselves are formed out of informational associations. Memories are 'written' as biologically correspondent associations, and 'read' as an observation of these areas of association. The significant informational storage density that thinking relies upon is achieved largely by a distributed layering of association patterns.

'Reading' a memory begins as recognition of a 'signal' pattern in a sea of 'noise'. Through repetition and environmentally interactive testing, the means by which to differentiate between relevant and irrelevant pattern associations is developed. Our ability to 'sort' the 'signal' from the 'noise' is thus reflexively feedback-looped to become progressively more accurate with regard to what our thinking interprets as 'signal'. As we ourselves change, and as our environments change, our apprehension of these 'signals' will likewise change, because our 'sorting' mechanisms rely on iterating tests of these 'signals' against such changing circumstances.

Did you know that our personal finances are mapped to our bodies by psycho-physiological mechanisms?

In modern society (at least in the US), money has come to be so thoroughly associated with well-being that possession of money lessens or eliminates both psychological and physical pain, whereas the loss of money strengthens or creates experiences of both psychological and physical pain. This effect is theorized to be a product of the way that money has become a guaranty of, and thus a functional substitution for, social benefits, including acceptance and inclusion.

Because social acceptance and inclusion can diminish or eliminate pain, including physical pain, and a lack of social acceptance and inclusion can produce or increase pain, our substitution of money for social benefits has made the two functionally interchangeable in many circumstances.

Along with conscious recall, or explicit memory, we possess another form of recall termed implicit memory.

This involves all of the things that are learned and remembered unconsciously. Implicit memory makes it possible to bring all our varietal experiences, even those accrued without our conscious knowledge, into the service of performing myriad complex tasks. It also enables us to perform automated tasks without consciously attending to the fact that this is occurring.

Remembering an experience amounts to creating and editing a movie about the past in the present, and using all of the information associated with a recollection to do so, regardless of when or how this information was associated with the experience being recalled. This means that factual and non-factual information is included in our memories, that new experiences have provided new informational associations that may or may not have been relevant to the experience being recalled, and that new categorical frameworks which have imposed upon out thinking can influence our ability to effectively recall what happened.

Personal and situational motivational factor preselect and edit our memories for us in ways that we are not consciously aware of. The way that questions are asked, the stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves, and the normative factoring of narrative towards conformity with perceived group norms all heavily influence what we 'remember' in a given moment about a given moment. As a result, many of our memories are as much imagined as 'real' and may change substantially over the course of time without our knowledge.

(There are of course externalized memories which we interact with by procedures of stymergy, and various forms of shared consciousness which may or may not be translatable into current language, but I will leave these subjects for future posts.)

The mutability of our memories has obviously not gotten in the way of societal development. But our variable and easily manipulated memories would make it challenging to (re)produce and navigate our complex society if it were not for the power of our shared stories to coordinate and synchronize how we think about things.

These shared stories contain our agreed-upon truths and their epistemological ground. They are one of consensual reality's main ingredients. So when I talk about the trancewar, I am referring to a basic conflict over who controls reality which is taking place in increasingly sophisticated, technologically-augmented ways.

For the academically inclined, here is a short list of the sources that I recall consulting for this post, ordered by first listed author's last name:

Abelson, R., P., K., & P., A. (2004). Experiments with People. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Asch, S.E. (1955) Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, November 1955 VOL. 1 93, NO. 5 PP. 31 -35

Ditto, P.H., & Lopez, D.F. (1992) Motivated Skepticism: Use of Differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 568-584.

Janet Metcalfe Eich, A Composite Holographic Associative Recall Model, Psychological Review 1 982, Vol 89, No. 6, 627-661

Russell H. Fazio, Mark P. Zanna and Joel Cooper, Dissonance and self-perception: An integrative view of each theory's proper domain of application Journal ofExperimental Social Psychology Volume 13, Issue 5, September 1977, Pages 464-479.

Leon Festinger & James M. Carlsmith (1959) Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203-210

Frey, D (1986) Recent Research on selective exposure to information. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Volume 19, 1986, Pages 41 -80

Galinsky, A. D. et al. (2006) Power and Perspectives Not Taken. Psychological Science December 2006 vol. 17 no. 12 1068-1074

H.G. Pope et al.,(2006) Is Dissociative amnesia a culture-bound syndrome? Findings from a survey of historical literature, Psychological Medicine 2007 Feb;37(2):225-33.

Roediger, H.L. & McDermott, K.B. (1995). Creating false memories: remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, Vol. 21 , No. 4. (1995), pp. 803-814.

Ross, L. (1977) The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortion in the Attribution Process. Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 10

Daniel L. Schacter Implicit Memory: History and Current Status, Journal ofExperimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 1 987, Vol. 13, No. 3. 501 -518

Daniel L. Sehacter, C.-Y. Peter Chiu, Kevin N. Ochsner (1993) Implicit Memory: A Selective Review Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 6:1 59-82

P. K. Smith et al, (2008) Lacking Power impairs executive function. Psychological Science May 1 , 2008 vol. 19 no. 5, 441-447