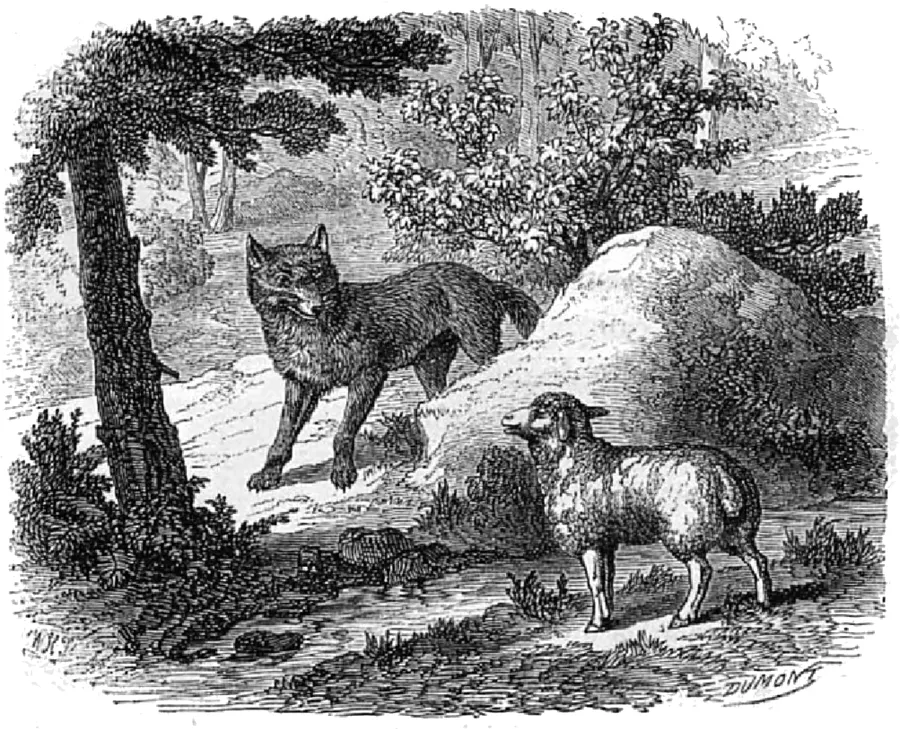

The Wolf and the Lamb

In this fable, the wolf acts as a conspiracy theorist: whenever the lamb shows him that he is wrong, he changes the subject.

Le Loup et l'Agneau

La raison du plus fort est toujours la meilleure :

Nous l’allons montrer tout à l’heure.

Un agneau se désaltérait

Dans le courant d’une onde pure.

Un loup survint à jeun, qui cherchait aventure,

Et que la faim en ces lieux attirait.

Qui te rend si hardi de troubler mon breuvage ?

Dit cet animal plein de rage :

Tu seras châtié de ta témérité.

Sire, répond l’agneau, que Votre Majesté

Ne se mette pas en colère ;

Mais plutôt qu’elle considère

Que je me vas désaltérant

Dans le courant,

Plus de vingt pas au-dessous d’elle ;

Et que, par conséquent, en aucune façon

Je ne puis troubler sa boisson.

Tu la troubles ! reprit cette bête cruelle ;

Et je sais que de moi tu médis l’an passé.

Comment l’aurais-je fait, si je n’étais pas né ?

Reprit l’agneau : je tette encore ma mère.

— Si ce n’est toi, c’est donc ton frère.

—Je n’en ai point.

— C’est donc quelqu’un des tiens ;

Car vous ne m’épargnez guère,

Vous, vos bergers et vos chiens.

On me l’a dit : il faut que je me venge.

Là-dessus, au fond des forêts

Le loup l’emporte, et puis le mange,

Sans autre forme de procès.

The Wolf and the Lamb

The reason of the strongest is always the best :

We will show it presently.

A lamb quenched his thirst

In the course of a pure creek.

A wolf came fasting, seeking adventure,

And that hunger in this place attracted.

Who makes you so bold to disturb my drink?

Said this animal full of rage:

You will be punished for your temerity.

Sire, replies the lamb, may Your Majesty

Not start to get angry;

But rather you should realize

That I am quenching my thirst

In the current,

More than twenty paces below you;

And that, therefore, in no way

I could disturb her drink.

You disturb it! replied that cruel beast;

And I know that you slandered me last year.

How could I have done it, as I was not yet born?

Said the lamb: I still suckle my mother.

— If not you, then it's your brother.

— I have none.

— Then it is one of your people;

Because you don't spare me much,

You, your shepherds, and your dogs.

I have been told: I must take my revenge.

An then, deep in the forest

The wolf takes it, and then he eats it,

Without any other form of trial.

First Fable: The Circada and the Ant

Previous fable: The City Rat and the Country Rat

Next fable: The Fox and the Stork

The Life of Aesop, by Jean de La Fontaine - part 2

Aesop was a slave. The first master he had sent him to the fields to plow the soil, either because he deemed him incapable of anything else, or to remove from his eyes such an unpleasant object. Now it happened that this master having gone to see his house in the fields, a peasant gave him some figs: he found them beautiful and had them put together very carefully, ordering his sommelier, named Agathopus, to bring them to him after his bath. As luck would have it, Aesop had business in the house. As soon as he entered it, Agathopus took the opportunity, and ate the figs with some of his comrades: then they told the master that Aesop ate the figs, not believing he could ever justify himself, so much as he stuttered and looked like an idiot! The punishments that the ancients used against their slaves were very cruel, and this fault was very punishable. Poor Aesop threw himself at his master's feet; and, making himself heard as well as he could, he testified that he only asked as a grace that his punishment be suspended for a few moments. This grace having been granted to him, he went to fetch lukewarm water, drank it in the presence of his lord, put his fingers in his mouth, and what follows, without returning anything but this water alone. Having thus justified himself, he made a sign that the others should be obliged to do the same. Everyone was surprised: one would not have believed that Aesop could have invented such a thing. Agathopus and his comrades did not seem surprised. They drank water as the Phrygian had done, and put their fingers in their mouths; but they were careful not to push them too far forward. The water did not fail to act and to show the figs, still raw and all vermilion. By this means Aesop saved himself: his accusers were doubly punished, for their gluttony and for their wickedness. The next day, after their master was gone, and the Phrygian at his ordinary work, some wandering travelers (some say they were priests of Diana) begged him, in the name of Jupiter Hospitaller, to teach them the way to go to town. Aesop first made them rest in the shade; then, having presented them with a light collation, he wished to be their guide and did not leave them until he had put them back on their way. The good people raised their hands to heaven and begged Jupiter not to let this charitable action go unrewarded. As soon as Aesop had left them, heat and weariness compelled him to fall asleep. While he slept, he imagined that Fortune was standing before him, loosening her tongue, and by the same means presenting to him that art of which he may be said to be the author. Rejoiced at this adventure, he awoke with a start; and waking up: What is this? he said: my voice has become free; I pronounce well a rake, a plow, all that I want. This marvel caused him to change masters. For as a certain Zenas, who was there in the capacity of intendant and who had his eye on the slaves, had outrageously beaten one of them for a fault which he did not deserve, Aesop could not help reproving him and threatened him that his mistreatment would be known. Zenas, to take revenge on him, went to tell the master that a prodigy had happened in his house; that the Phrygian had regained his speech, but that the wicked used it only to blaspheme and slander their lord. The master believed him and went much further; for he gave him Aesop, with liberty to do with him what he pleased. After Zenas returned to the fields, a merchant went to find him and asked him if for money he wanted to sell him some beast of burden. Not that, said Zenas; I have not that power: but I will sell you, if you will, one of our slaves. Thereupon, after Aesop was summoned, the merchant said: Is it to mock me that you offer me the purchase of this character? He looks like a waterskin. As soon as the merchant had thus spoken, he took leave of them, part murmuring, part laughing at this beautiful object. Aesop called him back and said: Buy me boldly; I will not be useless to you. If you have children who shout and are mean, my face will silence them: they will be threatened with me as if I was a beast. This taunt pleased the merchant. He bought our Phrygian three obols, and said laughingly: Praise the gods! I haven't made a great acquisition, to tell the truth; but I did not spend much money.