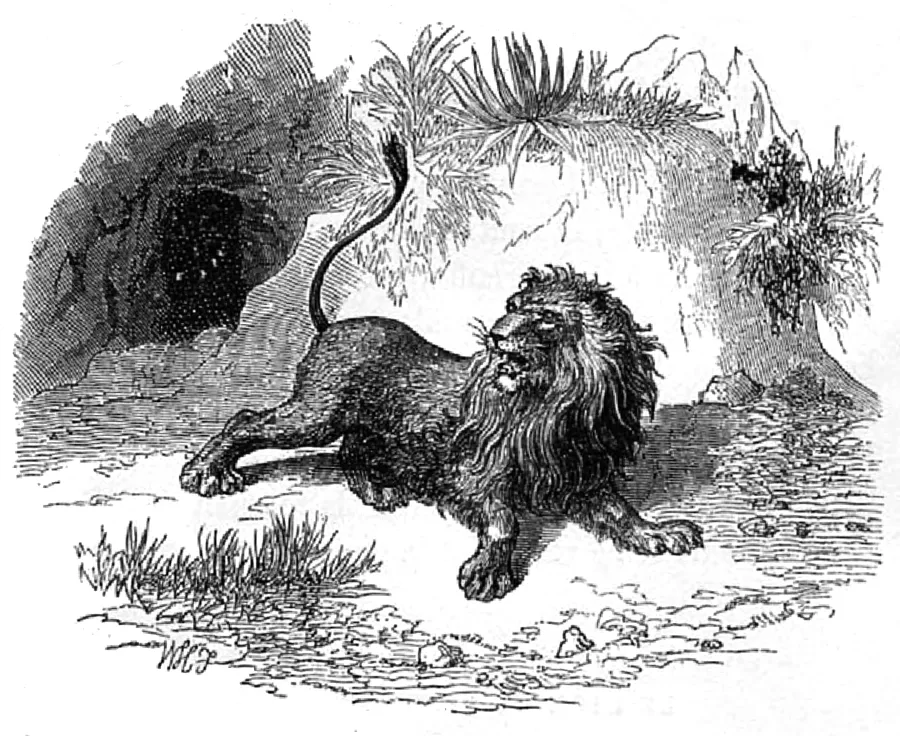

The Lion and the Gnat

Your most dangerous enemy is not always the biggest or the most obvious. And you should not lower your guard after an apparent success.

Le Lion et le Moucheron

Va-t’en, chétif insecte, excrément de la terre !

C’est en ces mots que le lion

Parlait un jour au moucheron.

L’autre lui déclara la guerre :

Penses-tu, lui dit-il, que ton titre de roi

Me fasse peur ni me soucie ?

Un bœuf est plus puissant que toi ;

Je le mène à ma fantaisie.

À peine il achevait ces mots

Que lui-même il sonna la charge,

Fut le trompette et le héros.

Dans l’abord il se met au large ;

Puis prend son temps, fond sur le cou

Du lion, qu’il rend presque fou.

Le quadrupède écume, et son œil étincelle ;

Il rugit. On se cache, on tremble à l’environ ;

Et cette alarme universelle

Est l’ouvrage d’un moucheron.

Un avorton de mouche en cent lieux le harcelle ;

Tantôt pique l’échine,

et tantôt le museau,

Tantôt entre au fond du naseau.

La rage alors se trouve à son faîte montée.

L’invisible ennemi triomphe, et rit de voir

Qu’il n’est griffe ni dent en la bête irritée

Qui de la mettre en sang ne fasse son devoir.

Le malheureux lion se déchire lui-même,

Fait résonner sa queue à l’entour de ses flancs,

Bat l’air, qui n’en peut mais ;

et sa fureur extrême

Le fatigue, l’abat : le voilà sur les dents.

L’insecte, du combat, se retire avec gloire :

Comme il sonna la charge,

il sonne la victoire,

Va partout l’annoncer,

et rencontre en chemin

L’embuscade d’une araignée ;

Il y rencontre aussi sa fin.

Quelle chose par là nous peut être enseignée ?

J’en vois deux, dont l’une est

qu’entre nos ennemis

Les plus à craindre sont souvent les plus petits ;

L’autre qu’aux grands périls

tel a pu se soustraire,

Qui périt pour la moindre affaire.

The Lion and the Gnat

Go away, puny insect, excrement of the earth!

It is with these words that the lion

One day spoke to the gnat.

The other declared war on him:

Do you think, he said, that your title of king

Scare me or worry me?

An ox is mightier than you;

I lead it to my fancy.

As soon as he finished these words

That he sounded the charge himself,

Was the trumpet and the hero.

In the approach he sets off;

Then take his time, and rushed to the neck

Of the lion, which he almost drives mad.

The quadruped foams, and his eye sparkles;

He roars. We hide, we tremble around;

And this universal alarm

Is the work of a gnat.

A runt of fly in a hundred places harasses him;

Sometimes stings the spine,

and sometimes the muzzle,

Sometimes enters the bottom of the nostril.

Rage then is at its height.

The invisible enemy triumphs, and laughs to see

That there is no claw or tooth in the angry beast

Who to make him bloody does not do his duty.

The unfortunate lion tears himself apart,

Rings its tail around its sides,

Beats the air, which does nothing;

and his extreme fury

Tired him, felled him: he is now very nervous.

The insect, from the fight, retires with glory:

As he sounded the charge,

he sounded the victory,

Go everywhere to announce it,

and meet on the way

The ambush of a spider;

He also meets his death there.

What things can we be taught by this?

I see two, one of which is

only between our enemies

The most to be feared are often the smallest;

The other is that from such great perils

some have been able to escape,

Who perished for the least business.

First Fable: The Circada and the Ant

Previous fable: The Bat and the two Weasels

Next fable: The Lion and the Rat & The Dove and the Ant

The Life of Aesop, by Jean de La Fontaine - part 9

Aesop's prediction that Xanthus would free him in spite of himself, turned out to be true. A prodigy happened which distressed the Samians very much. An eagle took off the public ring (it was apparently some seal that was affixed to the deliberations of the council), and dropped it into the bosom of a slave. The philosopher was consulted on this, both as a philosopher and as one of the first in the republic. He asked for time and had recourse to his ordinary oracle: Aesop. The latter advised him to produce it in public, because, if he did well, the honor would always belong to his master; otherwise, only the slave would be blamed. Xantus approved the thing and made him go up to the rostrum. As soon as he was seen, everyone burst out laughing: no one imagined that anything reasonable could be taken from such a man. Aesop told them that it was not the shape of the vessel that was to be considered, but the liquor that was enclosed in it. The Samians shouted out to him that he, therefore, say without fear what he judged of this prodigy. Aesop apologized as he dared not do. Fortune, he said, had put a dispute of glory between master and slave: if the slave spoke ill, he would be beaten; if he said better than the master, he would be beaten again. Immediately Xantus was urged to set him free. The philosopher resisted for a long time. Finally, the provost of the city threatened to do so from his office, and by virtue of his power as a magistrate; then the philosopher was obliged to set Aesop free. This done, Aesop says that the Samians were threatened with servitude by this wonder; and that the eagle removing their seal meant nothing but a mighty king who wanted to subjugate them.

Shortly after, Croesus, king of the Lydians, announced to those of Samos that they had to become his tributaries; otherwise, he would force them to do so with arms. Most thought he should be obeyed. Aesop told them that Fortune presented two paths to men: one, of freedom, rough and thorny in the beginning, but afterward very pleasant; the other, of slavery, the beginnings of which were easier, but the continuation laborious. He was quite cleverly advising the Samians to defend their freedom. They dismissed Croesus' ambassador with little satisfaction.