Scepticism and the non-position

Sextus Empiricus states that when we hold something as good or bad by nature, that we will never find ataraxia, and when we do not find this freedom from anxiety, we will never achieve a state of happiness. Sextus states that:

“For the person who believes that something is by nature good or bad is constantly upset; when he does not possess the things that seem to be good, he thinks he is being tormented by things that are by nature bad, and he chases after the things he supposes to be good; then, when he gets these, he fails into still more torments because of irrational and immoderate exultation, and, fearing any change, he does absolutely everything in order not to lose the things that seem to him good” (Outline of Pyrrhonism Book 1.27).

I propose that we read the above quotation in the following manner: The Sceptic or Pyrrhonian philosopher does not hold a position. This is called a non-position. From this non-position, no one can critique the Pyrrhonian or Sceptic because she does not hold any position. From this position it is possible to constantly critique our own way of being in the world and the status quo. Why do I say this?

The problem with any critique is that it comes from a position. This position is likely defended with the critique one is busy with. Whilst critiquing, say, some piece of art, one has in mind some framework or norm from which one is critiquing the artwork. This can be seen as a weakness in one’s critique. However, the Pyrrhonian does not hold a position, so she cannot have a weakness in her argument because she does not hold a position from which the critique derives. The Pyrrhonian, in this case, is the philosophical counsellor.

Philosophical Counselling as Emancipation

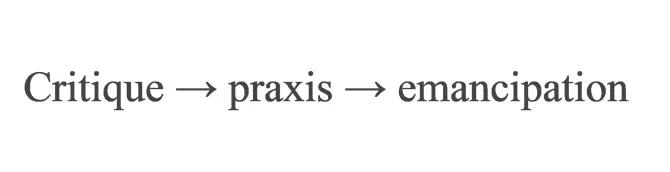

The philosophical counsellor, as Pyrrhonian Sceptic, does not hold a position; she argues from a non-position. This critique from a non-position becomes a lifestyle; she lives her philosophy (praxis). This brings a form of emancipation. Let me explain.

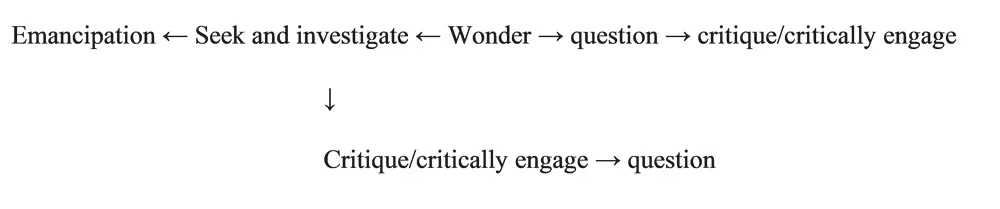

(Image based on Critchley (2001: 74).)

By not constantly wondering about “things” one will not question these “things”. By not questioning these “things” one will not critique; and by not critiquing on will merely “reproduce the status quo”. The philosophical counsellor should thus always wonder; never to stop critiquing and to always question things so to not accept (passively) the status quo. One might resemble it as follows:

By always investigating things, the philosophical counsellor will wonder, and this moment of wonder will instil a questioning and a need to critically engage with things. This in turn will again lead to a renewed will to question. Adopting this as disposition, the philosophical counsellor as being a Pyrrhonian Sceptic, will be emancipated or liberated from the status quo.

Finding Happiness in the Mundane

It is said that Pyrrho lived an exemplary life, a statue was erected of him in Ellis where he lived and that philosophers were exempted from paying taxes due to his lifestyle. It is also said that Pyrrho, in a storm whilst on sea, lied still and said to his fellow passengers be like the small pig who continued to eat while the storm raged on. From our contemporary perspective, this inactive stance seems problematic. We are constantly told to actively search for happiness or to fight for something we feel a strong affection for. However, as we saw in the writing of Sextus, this will only bring forth unhappiness and a state of disturbance. Some people might find a fleeting moment of happiness in fighting for what they believe in, but this is not a sustainable position. For how long can one actively fight for one’s position before that position becomes obsolete? This is the classic problem of the hedonistic treadmill: when the treadmill stops, one’s happiness also stops.

Let us take a step backwards. There is some tension in what I have stated above. On the one hand, when we do not hold anything as good or bad by nature, we are left with a feeling of passivity. On the other hand, we constantly need to seek and investigate to question and critically engage so that we might get liberated. How can we reconcile these two positions? How can we, on the one hand, be like Pyrrho who in the face of the storm act like a little pig undisturbed by the storm, and on the other hand, be like the Philosophical Counsellor constantly seeking and investigating things? I think there is no need for a reconciling here. The Philosophical Counsellor and the Pyrrhonian is not on the hedonistic treadmill. Instead, the Philosophical Counsellor and the Pyrrhonian is on a different journey. She accepts the mundane every day as the mundane every day, she does not seek to change it. However, she critically engages with the mundane every day. In this critical engagement, she finds happiness as a by product which she did not search for. By actively participating in life, she became liberated and found happiness not as a goal but as some offshoot which she did not even know existed.

Sources

Critchley, S. 2001. Continental Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sextus Empiricus. Outlines of Pyrrhonism. (Benson Mates Translation).