There is a very common tradition, used in many traditions and cultures, surrounding the campfire. The idea is that once you get the fire started, you don't let it go out. To achieve this goal, you must 'tend the fire'.

In simple fashion this means adding wood to it. But, depending on its state of decay since the last tending, you may also need to reorganize the elements of charred structure as it falls apart or perhaps apply some breath or other air flow. But you can't let it go out. Some rituals have certain members dedicated to tending, in my family we always took turns voluntarily.

Usually by the time morning comes, there are still red hot coals that can be coaxed back to life, even if everyone has been sleeping for many hours.

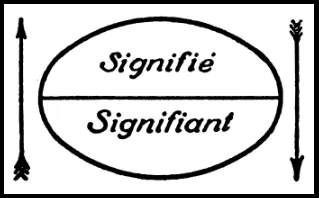

I'll remind you all of Ferdinand de Saussure, whose thoughts on the relationship between 'Signifier and Signified' are summed up in the above image from this source. Saussure was referring to 'signs' with this concept, a dual nature of communication - A sign which means something is also a meaning signified, notice the root word even though pronunciation changes. These are inseparable but demonstrably different.

Words are signs, and language communication is also dual in the same way, in that we have words which mean things, and things which are called words. This is less obvious until you learn another language - lots of people use completely different words to describe the same things - and there are different boundaries between words in different languages. Anyone who is bilingual can tell you, not everything is as easy as a word for word translation.

But we are describing the same reality. We can be looking at the same stone when one says rock and another says piedra.

And the same is true for symbols. Symbols can exist on many levels of interpretation, but some concepts are universal. Check out the Maps of Meaning Deep Dive Playlist for a full university course on this concept.

Fire is a word, its a thing we experience, it is also a symbol. Fire can mean different things, obviously its hot and dangerous, but its also warm and illuminating.

Think of the myth of Prometheus, who stole fire from the God's and gave it to humans. Remember, if you let the fire go out, you will have to kindle the flames all over again, but as long as the fire remains lit, its relatively easy to keep it burning.

The fire, originally from heaven, illuminates us in the darkness. In this case, and in many other stories of fire and rituals involving fire, we can see it as a symbol for the combined knowledge/culture of our civilization.

A phrase 'passing the torch' means handing down what was once given to you, usually to another generation of 'torch bearers' - think of the olympic tradition of running a literal torch around and handing it between people.

And this concept is neither new nor pagan, its in all cultures, including featuring prominently in the Bible, take a look at this command from God to the Israeli priests in Leviticus:

The fire is our cultural legacy. We have inherited it from others, long dead, and it has been carefully tended over centries, millenium. Now it is our turn, and there is no one else but us to do the job.

We have to tend it, which means sometimes adding more fuel, sometimes rearranging the structure when it breaks down or fails, sometimes knowing when and where to blow fresh oxygen into the mix. And the fire is always breaking down, that is its nature. Untended, it won't last long - for a campfire (and our culture) everyday is the end of the world.

Let's think a minute about one tiny aspect of our cultural heritage, that of our Roads.

The Romans were known as great road builders. They connected different parts of Europe and the surrounding world with them on their own path from republic to empire. As their empire fell apart, somehow the knowledge of building and maintaining these roads fell outside of people's understanding.

An observation that I believe originally comes from Dan Carlin, we are currently accustomed to thinking about ourselves as more technologically advanced than our predecessors, but this isn't always the case. For hundreds of years, more than one thousand, people used Roman roads as they slowly fell apart, and surely they thought about their ancestors - 'Who were these people and how did they do these things?'

Once this type of knowledge is lost, its not so easy to get it back.

Fixing the road is important, and apart from being a literal activity, its also a symbol for our culture. We didn't make the roads, they are our legacy, our inheritance. All we need to do is fix them, tend to them, keep the ditches clean and the middle high. Roads fall apart by themselves, through use and erosion - like fire, left untended, the roads will break down and eventually disappear all together.

In the small town of Convenio, there is a huge mango tree that is known for its enormous harvest of fruit, 600 bags of mangoes each harvest according to my interlocutor. It could be a hundred years old this tree, though I don't really know how to tell (and trees don't have rings in Colombia 😲).

Why don't we have more trees like this in the world? Its not hard to plant a mango tree, there's a big seed in every fruit. The hard part is not cutting it down for 100 years.

And of course - a big tree is its own symbol, often standing for the 'source of the wisdom of the ages'. We may not have planted the tree, but we do eat its fruits.

The webs of symbolism can be easy to get lost in, but we are talking about the real world, the reality.

The knowledge and practice of speaking a language must be shared and passed on, or languages die. Speaking is the act of preservation.

Knowledge and practices of road building must be shared and engaged in or the roads fall apart. Engineering does not spontaneously emerge, like a fire it must be tended.

Knowledge and practices of plumbing must be shared and engaged in, or before you know it the shit will start to pile up - there is much to be said about plumbing perhaps having a bigger impact on human health than medicine - and the pipes don't fix themselves.

Knowledge of medicinal plants and their uses must be shared and passed on - they are a botanical legacy that stretches for thousands of years.

Without culture we are wandering blind, unable to see in the darkness.

There is probably a future discussion needed about what are the most important values of our culture, what is is specifically that we have to be so sure to tend to, because it seems to me that not everyone is clear about what a miracle it is that we exist in such a state to begin with.

That we have roads, medicine, engineering, lightbulbs and internal combustion engines is a testament to the power of what has been passed down to us. House building, ship building, sea navigation and countless other fields of knowledge are applicable to this concept.

Some of what has been passed to us is perhaps not well understood, and recently I have noticed that some people think that its bad, hey let's put out this fire because someone got burned and it hurt and that's bad. But its going to get pretty cold and miserable without that fire.

Scientific rationalism is not moral, our values come from elsewhere, and we should keep that lesson close to heart as we tend the fire.