3.3.2. MiCA, enterprise blockchains and crypto-assets, and the EU “digital age”

-78. I concluded the previous section by observing that, notwithstanding its indiscriminate, “elephant in a china shop” approach, MiCA appears motivated by a certain economic pragmatism. The intention of the legislator appears to be to push out as fast possible a legal framework that should enable a regulated market in crypto-assets to take hold in Europe, with 400 million European as consumers and traditional financial firms in good position to “sell shovels and pickaxes”.

-79. As noted in section 3.2.2 above, once the financial firms have everything in place to provide crypto-asset services, they will also have a clear incentive to demonstrate the quality and effectiveness of their services and might want to exploit synergies by doing what in the IT world is referred to as “eating their own dog food”, i.e. by issuing crypto-assets which they would for instance immediately admit to trading on their own platform at no cost. To understand why being able to internalize that value-adding step, rather than having to resort to the market of CASPs, as a start-up would need to, may well make the difference between a profitable and thus sustainable business and an unprofitable one, we need to turn again to Coase’s 1937 analysis of “The Nature of the Firm” and the subsequent developments in “transaction cost economics”.

-80. A business arrangement between a crypto-asset issuer and a CASP operating a trading platform is complicated by the complexity of the underlying technology and the potential legal implications. It requires transaction-specific investments in human and physical capital and the efficient processing of information. The resulting high transaction costs justify vertical integration.

-81. Ian Macneil, in an early ’70-ies series of thoughtful and wide-ranging essays on contract law quoted by Oliver Williamson observes that “any system of contract law has the purpose of facilitating exchange”. The criterion for organizing exchange (commercial transactions) “is assumed to be the strictly instrumental one of cost economizing”. Economizing on transaction costs can be decomposed into reducing costs of gathering, assessing and processing information and reducing the risks of “opportunism”.

-82. MiCA provides a framework for standardized information that market participants are expected to produce and consume. It is as yet unproven law, so adaptations are expected to be necessary. “The advantage of vertical integration is that adaptations can be made in a sequential way without the need to consult, complete, or revise interfirm agreements. Where a single ownership entity spans both sides of the transactions, a presumption of joint profit maximisation is warranted.” At any rate, by internalizing crypto-asset issuance and crypto-asset service provision, financial entities will not be concerned by MiCA’s hostility toward disintermediation (Recital (36) and Art. 10(3)).

-83. It is thus worth asking: are there chances that incumbent financial entities will come up with innovative, unexpected kind of tokens? What kind of crypto-assets might they issue, beyond the run-of-the-mill?

-84. The question is relevant because in Part 1, section 1.2.3, I insisted that, in spite of many over-enthusiastic accounts, “blockchain” is not a “miracle”, general purpose technology and that most of the time, when presented as a solution to a problem, its inherent costs and trade-off have not been properly accounted for. Moreover, in section 3.1.2 above, I admitted that the “concerned.tech” group of signatories of the “Letter in Support of Responsible Fintech Policy” had a point when observing that most of today’s crypto-assets are merely vehicles for “unsound and highly volatile speculative investment schemes”.

-85. Back in 2018, one of the best economic thinkers in the field, Oliver Beige, was exploring potential answers to the question “why aren’t there real blockchain use cases yet?” Taking as a comparison autonomous driving, he noted it had been around since the mid-1980s, then interest in it faded away and was revived in mid-2000s, and that almost two decades later there’s still no autonomous car in production. He stated: “momentous inventions have momentous legal challenges.” In this respect, MiCA holds the promise of clearing a significant number of hurdles.

-86. Although at the beginning incumbent financial firms are likely to internalise crypto-asset creation, O. Beige observes that blockchain “is simply an accounting technology that shifts record-keeping and auditing from inside the productive unit to between productive units, which is where the basic unit of economic activity, the transaction, happens.”

-87. The firm, O. Beige writes in another post, “is still the strongest means to orchestrate the production of economic value.” And firms, in turn, “tend to swallow markets, like paper wraps rock.”, exemplifying with the stunning economic success of “internet platforms” such as Facebook, Uber, Google, Alibaba, Intercontinental Exchanges (ICE), to which he might have also added Amazon and even Apple (through its AppStore). That is because in a marketplace, matching buyers and sellers, but also stewardship and custodianship add value and allow the “swallowing” firm to extract rents in exchange for exclusive access. These rents are currently accruing to the big internet platforms. Blockchain- and crypto-asset-based enterprise systems can help smaller companies and “marketplace participants” disperse these rents and MiCA has the merit (if unintended) of clearing some of the legal obstacles such systems face today.

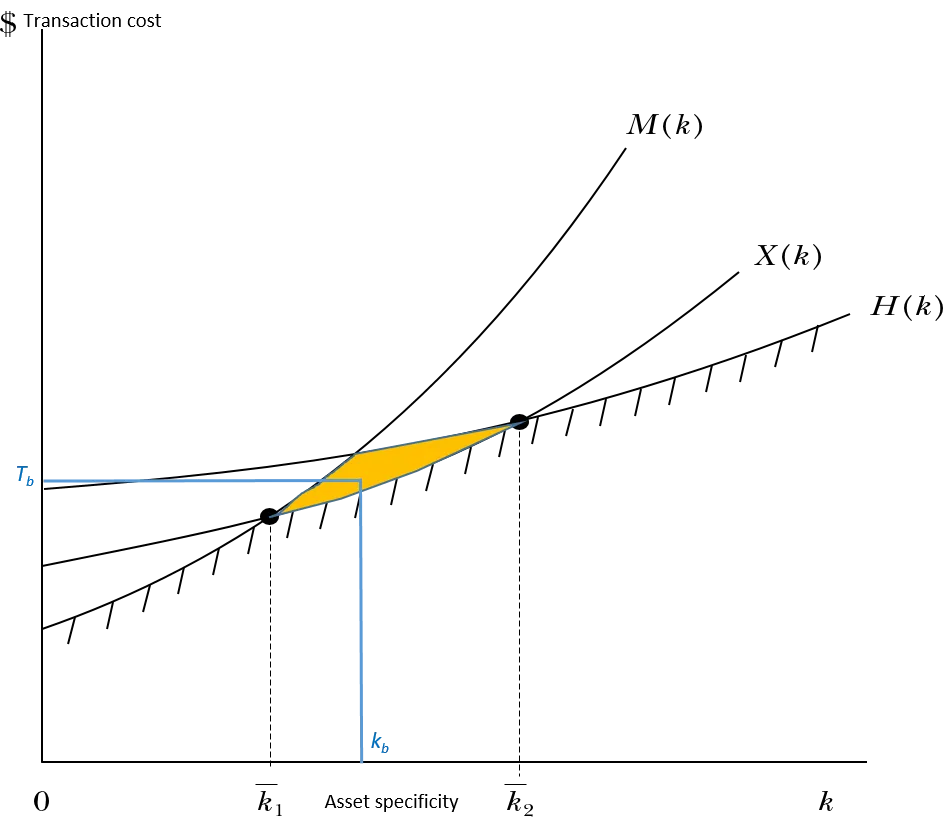

-88. The development path one can hope for is that, in time, smaller firms might be able to better withstand the competitive pressure of big companies by aggregating around virtual, consortium-governed markets supported by blockchain systems and crypto-asset-based accounting. From the point of view of economic theory, these could be hybrid modes of governance which are able to decrease transaction costs in situations where neither “hierarchies” (firms), nor classical markets can provide as good a solution (see the orange-shaded area in the Figure 7 below). Such novel governance structures can in the end offer European consumers more choice at better prices, while also increasing the much prized European “strategic autonomy”. This is another way of framing the arguments presented by P. Hansen in an article which I quoted in Part 2: “Europe’s Third Way is Web3: Why the EU Should Embrace Crypto”

Figure 7 Cost of governance for blockchain-based hybrid governance systems (X) between firms (H) and markets (M), adapted from Williamson

Figure 7 Cost of governance for blockchain-based hybrid governance systems (X) between firms (H) and markets (M), adapted from Williamson

-89. Beyond trying to predict how the European economic actors will respond to the changes in the legal environment, the more important question is: will MiCA contribute to “a Europe fit for the digital age”? Unlike semiconductors (computer “chips”) and artificial intelligence, crypto-assets and blockchain technology do not feature prominently in the Commission strategy, which tends to confirm the argument made above that the European legislators have not fully grasped the importance of the blockchain innovation and as a consequence MiCA is only a pragmatic, defensive answer to a technology phenomenon perceived to primarily challenge the established political and economic power structures, rather than seen as providing economic and political development opportunities.

-90. To sum up, by paving the way for a retail market in crypto-assets, MiCA also dispenses with some of the legal obstacles that have been hindering the development of enterprise blockchain systems, albeit fortuitously. Such systems have the potential to shift the balance (ever so slightly) in favour of smaller European firms and thus contribute to the objective of European “strategic autonomy”.

| Table of Contents | |

|---|---|

| <previous> | <next> |

[207] “Eating your own dog food”,

[208] O. Williamson, “Transaction-cost economics: the Governance of contractual relations”, Journal of Law and Economics, 1979

[209] ibid., p. 236

[210] ibid., p. 245

[211] ibid., p. 253

[212] O. Beige, “Y no real blockchain uses cases yet tho?”, 2018

[213] O. Beige, “A ballad of accounting and technology”, 2019

[214] O. Beige, “Just another database format? On blockchains, governance, enterprise systems, and economics”, 2019

[215] O. Beige, “Markets, enterprises, and data: blockchains and the role of disintermediation”, 2018

[216] ibid.

[217] O. Beige, “Blockchains as rent-dispersing Aumann machines”, 2018

[218] O. E. Williamson, “The Theory of the Firm as Governance Structure: From Choice to Contract”, Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 16, Number 3, 2002

[219] P. Hansen, “Europe’s Third Way is Web3: Why the EU Should Embrace Crypto”, op. cit.

[220] O. E. Williamson, op. cit.